I have been asked by many people to write or record a memoir summarizing my life experiences and my thoughts regarding the different events that I went through. I have always been reluctant to go through this process for many reasons, the most important one being privacy. I felt strongly that the memories of events I had gone through are private matters that must be kept to myself. However, it is of some value to transmit to my family some of the lessons that I learned in the hopes that they would benefit from them.

The idea of this book started about ten years ago, when we were able to go to Palestine more often to spend time with the family. During these visits, I found that the younger generation of our family did not know the history of our country and our people. I was spending time with some of them talking about the past, and I found that they were eager to learn more, so I decided to leave them with a brief written history to learn who they are and find out about their roots. I felt that it was my duty to take the time to write a book telling the story of our land and its people.

I initially focused on the history of the Israeli invasion of our country, how it

started, and whom it involved. I began gathering references so that I would be able to write an accurate narrative. I did not intend to make a lengthy and detailed history, and I definitely was not sure whether this writing would be available as a text to others or just a biography for my family.

In the process of writing I discovered that, as much as I knew, it was definitely very little. This became a study project for me, and I enjoyed it, as I was a good reader; it was a great pleasure for me to learn more. As time went by, I started collecting references. I expanded my project and decided to go as far as I could to learn how Palestine had developed since the earliest humans inhabited it, and to follow the thread of how they were able to create a great culture and an advanced civilization.

Palestine

Palestine is part of Greater Syria, one of the oldest places where humans settled and developed into communities and nations. We call our country Canaan, and the people of the country are the Canaanites. I learned that Canaan (Kanaan), meaning lowland, refers to the coastal plains that extend from the south all the way to the northern Syrian coastline. It also includes the plains that connect the coast with the interior. I also learned that Aram and Amoro refer to the area west of Mesopotamia. The Mediterranean Sea was called the Sea of Amoro. This land was the place where the Semitic languages evolved and developed. The Phoenicians were Canaanites who

gave the world the alphabet and the origin of all the world’s languages.

Palestine has some of the oldest cities of the world, including Jericho, which is considered the world’s oldest inhabited city. (Nablus, along with Damascus, is also one of the five oldest cities in the world.) Palestine is the birthplace of monotheistic religion, as the early concept of God evolved in this land. Palestine was also the place of domestication of many plants, especially olive trees, that were later brought to other regions of the Mediterranean. The Palestinians domesticated the olive tree more than six thousand years ago when they moved from the highlands to Jericho because of the drought and because of the rich springs of that city. As they spread olive trees throughout the entire Mediterranean basin, they also spread monotheistic religion to the world.

Over its long, rich history, waves of immigration and invasion brought new

people to Palestine. Those who remained assimilated with the existing population and contributed to the development of its culture and technology. Religions came and went, and were adopted by different groups—but always, all those people, who endured invasion, flood, famine, and drought, were Palestinian. Those who tilled the land, died for it, were buried in its soil generation after generation, who faced armies and conquerors and prevailed to build their homes there—all are Palestinian. No single ethnic, tribal, or religious entity can lay sole claim to this land; they are us, and we are them. We are all Palestinian.

Proud to be a Kanaan

As a Kanaan born and raised in Nablus, since childhood I have been aware of the special and honorable roots that have guided me throughout my entire life. I have always been proud of who I was and who my parents were, and who the Kanaans are. Although I did not know my father, who passed away when I was not quite two years old, I knew a lot about him from my immediate family, from other members of the Kanaan family, and from friends who were very close to him. He was known for his honesty, generosity, and kindness. He did not leave us with many material assets, but he bequeathed to us his sterling reputation. I heard so many stories about him that always lifted up my spirits, especially during difficult times.

My mother, Rabeha, who took charge of the family after the early and unexpected death of my father, was a most noble lady. She devoted her life to keeping the family together and to facing every difficulty bravely and honorably. She was the best example of pride, courage, and self-control. She was the best of teachers for me and for my brothers and sisters. She taught us the right meaning of family and of our responsibility towards each other. As long as I am alive, I will never forget her advice to me to always be respectful and loyal to all members of the family.

Forever in my memory are my brothers and sisters Nasouh, Rihab, Ribhai, Adli,

Wisam, Siham, and Faisal, who rose up to meet their highest responsibilities and worked hard to make our family an exemplary strong, proud, Palestinian family. Likewise, I will never forget Uncle Abu Najdi, my mother’s brother, a prominent figure in our life who stopped at our house every day after he closed his shop to check on his sister and her children.

The love and guidance that I received from my family, especially from my mother, during my childhood, is beyond imagination. As the youngest member of the family, I was the center of attention for everybody. There was great emphasis on education and learning. My family was aware of my potential, and everybody invested the time and effort to make sure that I excelled in school. My sisters spent time with me every evening reviewing my school assignments before going to bed. Besides the good genes I was fortunate enough to inherit from my parents, I was blessed by this great attention and mentoring that was behind my achievements in school and being the head of my class throughout my entire life.

Proud to be Palestinian

Love for my country and my people have filled my heart since early childhood.

The events of 1947–1948, which are known in our history as al-Nakba (the

Catastrophe), affected the lives of Palestinians greatly. It established a dangerous base for colonial powers in the heart of the Arab world by cutting the Palestinians out from most of Palestine’s lands. Most of the people of Palestine were forced out from their cities, towns, and villages during the war. Multiple war crimes were committed by the Zionists against the Palestinians, and massacres were planned by the Zionist militias in several villages to create a state of horror and fear to drive civilians from their homes.

That year I was nine years old in Nablus, and I remember very well when masses of Palestinian refugees flooded our city. Schools were closed so that people could shelter there, as well as in churches, mosques, and camps set up with tents. I remember people were calling for volunteers to help people settle down, to bring food and other supplies. Despite my young age, I remember it because it was a completely different time in our city. Everybody was talking about the trouble they had been through, recounting their stories of how they had been expelled from their homeland. During the upheaval that

we call the Nakba, as a mere boy of nine, I started to live a new life. This experience had an enormous impact on my awareness of the Palestinian situation and my affiliation and belief in the justice of the cause, which became the motivation behind all my activities.

Al-Najah School

Through my nursery school, primary school, and secondary school years, I was enrolled in al-Najah school (najah means “success”). The history of Palestine was an essential part of the educational programs at my school. Many bright young students from all over the Arab world—North Africa, Algeria, Yemen—attended al-Najah school as boarding students. They opened new horizons for me that were the nucleus of my political and national awareness. Several of the school staff were eminent scholars and leaders in the Arab National Movement.

Nablus, my hometown, was one of the main Palestinian resistance centers against the colonial British forces and the Zionist militia. It was known as the Mountain of Fire.

Al-Najah school was a center of national spirit, and all graduates carried that spirit. I was proud to be among the graduates then, and I got involved in debate. I learned how to give political speeches and engaged in political and cultural activities.

The Arab National Movement

During the school year, I learned a lot about the history of the Zionist movement and the history of Palestine, and that was when I got involved in politics. At that time there were many groups, and I was exposed to all the ideas and political parties that sprang up in response to the Nakba.

At that point, I became aware of the Arab National Movement and its clear understanding of the nature and danger of Zionism—most importantly, that this threat was not limited to Palestine, but extended to all Arab countries, especially those of Greater Syria. The ideology of the movement, which focused on Arab unity as the strategy to combat the Zionist colonial agenda of expansion and expulsion, attracted me and convinced me to become a member and supporter.

My membership in the movement was a journey full of risks, and my history was full of obstacles and pain. It was a commitment that shaped my destiny and my life for many years to come.

The Genesis of the Movement

The idea started among Palestinian students at the American University of Beirut (AUB). The main person among the founders was Dr. George Habash, a Palestinian medical student from the town of Allud, who had been in his final year when Israel was established in 1948 and the people of Allud, including his family, were expelled. Another of the leaders of the movement was Dr. Wadie Haddad, who was a close friend of Dr. Habash. There was also a Syrian, Hani Hindi, and many other students. The AUB, and Beirut in particular, were at the center of Arab nationalism at the time. Different cultural movements were active, as well as several writers and authors who adhered to different ideologies.

The founders of the movement were aware of the Zionist plans to take over

Palestine and to transfer and expel the Palestinian people from their homes. While Zionists were using the slogan, “A land without people for people without a land” and claiming that Palestinians did not exist, they were well aware that Palestinians had in fact lived there for centuries and had a vibrant civil society. Their plan was to banish people to the most distant place possible (in their minds, this was Iraq). The program of the Arab National Movement showed a clear understanding of Zionism, its strategy, and its vision of the future of Palestine and the Palestinian people, as well as its expanded role in the entire Middle East—which basically would involve taking

over Greater Syria. That was very clear for them.

More importantly, what made me join that movement was the solution that they were advocating. They believed that the issue did not concern the Palestinians alone, but all Arabs, especially the Arabs of Greater Syria. They were also aware from the start that our problem was the vassal states—the Arab regimes whose rulers served the interests of the British and the Americans so that they could retain power and reap financial benefit. The movement understood that there was no way to prevail against the Zionists without regime change in the Arab world. At the same time, it was clear that the problem was not only the Jews who had settled in Palestine, but the imperial colonial powers of the British and US, who had created Israel as part of their strategic plan to control the region and to serve their interests in faraway lands.

Medical School

The second stage in my political involvement and in my future plans was going to medical school. I wanted to attend medical school in Egypt because its standard of education in medicine was considered the highest in the region.

I graduated from al-Najah school in 1955–1956. The educational system in Jordan consisted of eleven years followed by a matriculation test, but Egypt required twelve years of high school and passing a standardized test. As I wanted to attend school in Egypt, this created a dilemma. I owe much respect and gratitude to Dr. Qadri Toukan, who was the school president at the time. He managed to add a night class to meet the Egyptian requirements to be accepted to medical schools there. Thanks to him, I was able to attend the night classes and take a teaching job during the day. I taught mathematics, first in the village of Burqa and then in Nablus, and was able to connect with the students and instill in them national aspirations and the love for our country.

Meanwhile, I applied to medical schools in Egypt. Egyptian schools had a quota for Palestinian students in different specialties; the medical school quota was ten seats divided between the University of Cairo and Ain Shams University in Cairo. I was accepted at Ain Shams.

Funding, however, was a problem. My family was not wealthy and resources were tight. My mother called a family meeting at the house without me present, and they came up with a plan to meet my expenses. My two sisters earned a good income as teachers, and funds for my education were secured.

The First Year

At the start of my first year of medical school, as I was looking at the schedule, standing next to me was a young man with a friendly face who introduced himself as Bashir. We hit it off right away, and from that day our friendship grew. The first year was difficult because I was living with other members of the party who also went to Ain Shams, and our place was far from campus. It took me forty minutes by bus to get to school. By the next year I had gotten to know the city better, and with Bashir’s help, we moved to an apartment in Hiliapolis, New Cairo, with two other students, Anan and Ghassan. The place was owned by a very nice Saudi gentleman who lived in Cairo. We had a good relationship with him, and it was a fine living arrangement. We had two bedrooms; I shared a room with Anan while Bashir shared the other with Ghassan.

As for the academic aspect, learning in medical school in Egypt was almost impossible. Lectures had more than five hundred students in a huge auditorium. The lab was more reasonable. The program consisted of a year of premedical studies and five and a half years of medical studies. The first two years were combined, with one exam at the end.

I was involved in the Palestine student union, the Rabita, in Cairo. I can say with- out exaggerating that I was the most prominent, the first in elections, and had connections with students everywhere in Cairo. The union played a great role in the life of Palestinians. Interestingly, the All-Palestine Government, which had been established in Gaza in 1948 and survived for one year before being forced to move to Cairo by the Egyptian government, 1 was renting offices in the same building in downtown Cairo as the Palestinian Student Union. In fact, the student union was paying the rent for the All-Palestine Government.

The student union held many activities. The previous generation of leadership had been in the hands of the communist students and the Muslim Brotherhood. Yasser Arafat was an immensely popular member of the previous generation. He used to win elections by transporting busloads of Muslim students from al-Azhar university to cast their vote in his favor. By the time I arrived, however, Arafat was retired. The new generation had several parties besides the Arab National Movement that I belonged to. I won the elections in the year that I was there. In fact, I did not pay much attention to my studies that year because of my involvement in the student union.

The United Arab Republic

In February 1958, the United Arab Republic (UAR), a union between Egypt and Syria, was established. Civil society in Syria at the time was influenced by a number of different parties, including the Ba’ath and Communist parties, and several military nationalists. It had been a center of nationalist movements since the First World War. After 1948, there had been many attempts to take over the Syrian government. In 1958, the regimes in Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Jordan had conspired against Syria. The union between Egypt and Syria was formed to protect Syria from the attempts to overthrow its democratically elected government. I was present when people gath- ered to witness Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt and the president of Syria, Shukri al- Quwatli, announcing the establishment of the union. That was a dream, and a special day in the history of the National Arab Movement.

Sadly, that union ended in a military coup three years later. Behind its downfall lay the way it had been established and how it was administered. There were grievances among the Syrians that their sovereignty had been compromised. Nasser had agreed to the union on the condition that the political parties in Syria dissolve them- selves, and they agreed. But Nasser never intended to share power equally, and slowly squeezed Syrians out of influential government positions. He imposed economic reforms, including nationalization of many industries, creating backlash among Syrian businesses and the military. Military officers staged a coup and withdrew from the union in February 1961.

The other major event of that year, which took place only six months after the Arab Union, was the July 14 Revolution in Iraq, known as the 1958 Iraqi coup d’etat. It resulted in the overthrow of the Hashemite monarchy that had been established in 1921 when the occupying British government had installed Faysal I as king of Iraq. 2 The July 14 Revolution, which was extremely bloody, ended with the establishment of the Iraqi Republic. The Hashemite Arab Federation between Iraq and Jordan that had been established six months earlier also came to an end. Abd al-Karim Qasim, a Communist, took power as prime minister in Iraq until February of 1963, when he was overthrown and killed in the Ramadan Revolution by the Ba’ath Party’s Iraqi wing. Qasim’s deputy, Abdel Salam Arif, a non-Ba’athist, was given the cere- monial position of president, but the real power was with the top Ba’athi generals. Under these generals, a dictatorial police state took control of all aspects of power, including the National Guard militias, and organized massacres of hundreds, if not thousands, of suspected Communists and other dissident rivals, including members of the Arab National Movement. (This detail will become important later in my story.)

In the summer of 1958, when I returned to Nablus after my first year of medical school in Cairo, the situation in Jordan was very tense, as army officers whose nationalistic feelings had been encouraged by the Arab Union were attempting to topple the monarchy in Jordan. In the wake of the Iraqi revolution, public opinion was in support of the movement, and demonstrations filled the Arab streets. I was one of the prominent people in these demonstrations.

The Jordanian secret service and loyalist factions of the army were able to sup- press the movement. They also cracked down on everyone who participated, and I was targeted for arrest and imprisonment. The intelligence service came to my house in Nablus, but I was able to escape and went into hiding. After few days I came back, figuring it would be the last place they would look for me. Plans were then made for me to escape to Syria with other wanted people.

By September, arrangements had been made, and I left Nablus, traveling by car and sometimes by donkey, bound for the Jordan valley at the northern border of Syria close to the Sea of Galilee. We crossed the border into Syria legally; thanks to arrangements with Syrian authorities, we spent one night in jail and then were released. I spent several days in Syria and lived in the same house with Dr. George Habash, which gave me time to get to know him in person and spend time with him and learn from him. He was charming, kind, sincere, and loyal. He had a clear vision of the movement, and was able to express himself well and teach others about it.

Dropping Out of Medical School

When the school year started in the fall of 1958, I returned to Cairo to start my second year of medical studies. However, I was approached by the leadership of the Arab National Movement, who were looking for professional activists and organizers who would devote themselves to the activities of the party. The movement’s leadership asked me to leave my medical studies in order to devote myself to the movement’s political, intellectual, and social activities in Syria and Lebanon. Although I had done well in my first year, I decided to quit school and devote myself to the cause.

So I left Cairo in 1959. During that time I was traveling to Lebanon and Syria, which gave me more opportunities to meet with Dr. George Habash and Dr. Wadie Haddad, the two leaders whom I liked and respected. The Lebanese members who ran the party journal were smart, but I did not trust them and did not get along with them or build a strong relationship with them.

In 1961, the night before the military coup that resulted in the breakup of the Arab Union, I was in Damascus preparing for the National Student Union convention. This was to be to the first convention of the Palestinian Student Union, which would announce the establishment of the union with branches in countries throughout the Arab world and especially in Europe. The convention was to begin that night with speeches; the following day, we planned to officially establish the Palestinian Student Union at the convention. There were delegates from different countries, and everyone was excited. I was the moderator of that evening’s speeches, and I was to be announced as the president the next day. We all were excited that night, even though everyone was aware of the serious attempts by the regressive regimes to break the Arab Union between Egypt and Syria. In my speech, ironically, I stated that the union was stronger than ever.

But the next morning, on September 28, 1961, the military coup took place that resulted in the breakup of the United Arab Republic. Interestingly, the officer who led the coup was the secretary of the Egyptian general Abdel Hakim Amer. Amer had trusted him, and had given him control of the country after the removal of Syria’s previous leader. In my opinion, the UAR was controlled by the Egyptian secret service, which allowed the Syrian military officers who worked with the repressive regimes to succeed in breaking the union. Another major mistake on Nasser’s part was that when a group of Syrian officers in northern Syria declared a mutiny against the coup leaders, Nasser declined to send Egyptian military support to support them and protect the UAR.

Sadly, on the morning of the coup there were minimal protests or demonstrations in the streets, which indicated that people were relieved to get rid of the abusive Egyptian military officers and the mistakes they made. They only realized later who was really behind the new regime—the CIA and the Arab reactionary governments. It was sad for me to observe this. They believed the army’s claim that the coup was meant to correct the union, not abolish it.

Pursuing a Master’s in History

I moved to Beirut after the breakup of the United Arab Republic. I enrolled in Beirut Arab University (BAU) and studied history for four years. Attendance at BAU was very relaxed, and I hardly attended classes, as I traveled a lot, but I took the exams when offered. Because of this, I was always ahead in spite of my absences. I remember that one of the tests I took had a question about the French Revolution (which, as you may remember, began with a revolt against the king and ended with the dictatorship of Bonaparte). The question asked by the professor, a very knowledgeable Egyptian, was: “Did the French Revolution succeed, and how would you assess it?”

This untraditional question was interesting, and I answered it with one of the best essays I have ever written. Tests did not have the student’s name on them; they were only numbered, and grades were listed accordingly. During another written exam, the professor walked around as the students worked. He stopped by my chair when he identified my handwriting and shook my hand, congratulating me. He said, “I have never had a student like you.” That was very encouraging to me and gave me more motivation to study.

Imprisoned in Iraq

I received a baccalaureate degree in history from BAU in 1964, but I was not able to complete my master’s thesis at that time due to the political situation in Iraq, which caused a fundamental change in my life. The Ba’athist coup in Iraq in 1963 had been followed by a policy of repression and dismantlement of all political parties, including the Arab National Movement. The leadership of the movement decided to send a vanguard of students from different countries to try to rebuild the organization in Iraq; I was one of this group. I left for Baghdad at that time.

We took precautionary measures, and connection between members was limited. I lived in one house by myself and knew only one other person in another house. Somehow the Ba’ath regime found out about it. The way they operated was when they arrested one person, they subjected him to torture and extracted a confession to arrest another, and so on. Thus, when I went to the one house I knew and knocked on the door, the Ba’ath secret service opened the door and arrested me.

At that time I identified myself as a student just visiting a friend, but I was still arrested and kept in jail among tens of people in one big room. Nobody interrogated me for a while, unlike the others, and I felt comfortable, thinking that I would be released soon. Unfortunately, one of the people in the room who had confessed and apparently broke under torture recognized me by my code name, Yousef, and told the officers about it. They had been looking for Yousef and had been unable to find him until now.

I was removed to isolation and taken to the torture chamber. I do not want to elaborate on that time. Fortunately, the information I had was limited, and I tried to use my head and be wise about what information to give. Still, they subjected me to all kinds of physical torture. Much of the time I was unconscious and not aware of what was going on. Apparently other people were subjected to the same kind of treatment. One of them was a student who came from Cairo, from a prominent Palestinian family. I had never met him, but I knew of him, and he apparently knew of me. He was also tortured—so severely that he died. News about the persecution and death of members of the Arab National Movement spread all over the Arab world. My name was mentioned in a radio broadcast as one of those who had died under torture. Public opinion condemning the Ba’ath regime in Iraq grew strong, which forced them to release many prisoners, including me. I left Iraq and returned to Beirut.

My brothers and sisters thought I was dead, and they were devastated. They called a family meeting, and just as they were about to tell my mother the news, I called the phone in Nablus from Beirut to say, “It’s me! It’s me!” Everyone was greatly relieved, and the whole city of Nablus rejoiced.

Freedom

I received a warm reception upon my arrival in Beirut and was informed of what had transpired in my absence in prison. Unfortunately, a split had occurred among the elements of the movement. The main wing was led by Dr. George Habash, while the opposition movement was led by Nayef Hawatmeh, whom I never liked; Hawatmeh wanted to take the party toward a Marxist-Leninist ideology.

I attended most of the meetings and discussions aimed at healing the rift and avoiding negative publicity. It was agreed that we would call for a convention to dis- cuss the movement’s ideology and direction. One important topic on the agenda was to turn the leadership over to a younger generation that was not involved with either wing. My name was among the nominees for temporary leadership, but that meeting did not materialize. In any case, this series of events was very psychologically shocking and disillusioning to me, and felt far from the path that I had envisioned for the liberation of Palestine.

I spoke with Wadie Haddad about my disappointment and the toxic atmosphere that prevailed in the movement. He suggested that I take on a new mission of an educational and intellectual nature in the West Bank. This was appealing, as it would give me the opportunity to educate youth on the history of Palestine and the Zionist movement. I did not even know the full names of the youth I was working with; no infiltration of the border with Israel was committed by anyone I worked with, and that section was safe from the Jordanian intelligence during the time I was there. However, in spite of all the precautions taken, the Jordanian intelligence service, whose chief was Mohammed Rasoul al-Kilani, gathered a lot of information about all the political parties in Jordan and the West Bank and started a campaign of breaking up these groups. They arrested hundreds of people from all parties whose names were known to them without specific charges.

I was arrested and taken to Amman, where I was placed in the regular jail, which had been emptied to accommodate the large number of arrests. We could talk among ourselves, but we did not know what the situation was. From time to time they would take one or more of us to be interrogated, but the people who were interrogated never came back. I spent several weeks not knowing what was going on.

When my brother Adli, who was visiting from the US, found out that I was in jail, he managed to come see me through some connections. He gave me a message from my family urging me to leave politics and return to medical school. One day I was taken from the general prison to the center of the intelligence branch, where I met M. Rasoul and Adli. It was a strange meeting. Rasoul was talking to me, telling me to think logically, that the intelligence bureau had all the information that they needed on me, but asked me to take my time to think about it.

Afterward, I was taken to one of the isolation cells. Several nights passed with no one talking to me; they brought me food, and I slept sporadically. Then, early one morning, I was told to come to a special large room with Rasoul and other officers, as well as members of the Arab National Party who knew me and were familiar to me. At this gathering, Rasoul would ask the others to tell me what they knew. He would then ask me to do the right thing and write down any information I had. I wrote what I had deduced that my captors already knew. Fortunately, they did not know about the people I worked with. It was shocking to me to see this meeting conducted in a friendly way, with them joking and talking and enjoying good food. From that day on my treatment was different. I had to answer some questions in writing, and shortly afterward I was released.

The members of the Jordanian intelligence service that I dealt with were smarter than the ones I had dealt with in Iraq. They managed to get all the information without creating bad publicity for themselves, and at the same time managed to break apart not just the leadership, but entire organizations and all the parties without exception. Whether they had informers who infiltrated the parties, or whether members broke down under torture, they succeeded in dismantling the political life in Jordan for a comparatively small price. Furthermore, anyone who was arrested in Jordan for political reasons faced a difficult life; they were banned from employment and forbidden to leave the country.

Life Decisions

My disappointment and disillusionment after all these events, along with many other reasons, led me to make the decision to be done with politics. I did not know what to do or what my future would be, so it was a difficult period of my life. But as I was faced with all this, I received a letter from Cairo from my dear friend Bashir, who had been my roommate and had graduated from medical school as a specialist in obstetrics and gynecology. 3 He advised me to go back and finish medical school. That sounded so ridiculous at the time, as I had been away for five years, not to mention the difficult question of funding. When I mentioned this to my brother Faisal, however, he encouraged me, and promised to secure the funding for my education himself. He was by then a successful dentist living with his young family in Nablus.

The sticking point was whether the medical school would allow me to enter the second year of study after a five-year absence and to have the successful results of my preliminary year recognized. After persistent effort, and thanks to a decision by the office of President Nasser (this was due to Bashir’s good relations with the top level of government), I was accepted, and my absence was considered justified. Despite the reservations of the head of the Faculty of Medicine and his warning that I would fail, I made a very serious effort and passed the two-year exam with distinction. I graduated in 1970 with first-class honors. The credit goes to my family, especially to the blessings of my mother and my brother Faisal and his wife Fatima, who provided me with the financial support for my academic journey.

Faisal was deported by Israel to Jordan in 1969, so my brother Adli secured a loan for me for that year, which I paid back after I started my medical practice. I continued my career with pride and sincerity. My goal was to continue my studies in the United States, specializing in the field of neuroscience.

One of the requirements to be admitted to medical school in the US is passing the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG), which I took at the American embassy in Beirut. This was a very difficult exam, but I passed, coming one step closer to going to the US.

Shadia

In my last year of medical school in Cairo, my brother Faisal sent me a letter conveying the family’s approval of my plans to go to the United States. In his letter, he suggested that I visit Nablus in the summer to have a chance to meet Shadia in the hopes that we would like one another and agree to get married before I left for the US. That idea appealed to me. I remembered her as a beautiful young college girl—we had briefly been introduced when I visited the library at the University of Jordan in Amman with my brother Faisal to donate my brother Adli’s chemistry books.

While I was in the midst of taking my last two comprehensive exams in medical school, Faisal came to visit me, staying until I was done, to break to me the devastating news of my mother’s passing due to a heart attack. This weighed heavily on my heart throughout my life, as I had always dreamed of the day that I would be able to make her comfortable.

Because I had not been present at the time of the 1967 occupation of the West Bank, I was not counted in the census and was therefore not considered a resident. The census was conducted door to door, and anyone who was not present at the time was denied residency status. The census had been timed with the knowledge that students studying abroad would not be present, as well as families working in the Gulf states who would return to their homes in the summer. This strategy reduced the numbers to better fit the Zionist fiction of a “land without a people.” My sisters, who were residents, succeeded in getting me a visiting permit to Nablus.

In Nablus, I waited for Shadia to arrive from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, where she had gone after graduating from the University of Jordan. Upon her long-anticipated arrival, we were introduced at her home. Shadia’s mother, who was recently widowed, gave permission for me to visit and spend time with Shadia. For weeks that summer, I would visit her at her home and spend all day with her and the family to get to know her. I would leave in the evening when the taxi service was ready to end for the night. We spent hours talking. I found more than I expected in her, and I enjoyed her intellect and sense of humor.

One night when I returned home, I received a call from the police station, which was manned by Palestinian police under the control of the Israeli officers, inviting me to come to the station. I was asked if I wished to have their police car pick me up, but I decided to walk across town to the station myself. The minute I arrived I was put under arrest. I was transferred to the city prison, where I found a large crowd of other Palestinians. A large number of women were detained at the same time in other quarters of the prison. I spent three weeks in detention, but was never interrogated. When an Israeli officer asked me if I knew why I was there and I said no, he told me it was because there were Israeli hostages on several planes in the Jordan desert that had been hijacked by the PFLP, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. 4 He explained that my brother Faisal, who had been deported from Nablus the year before, was a political supporter of that group. I replied to the Israeli officer that the whole population were hostages, and there was no need to take us. He told me that if I had not been at home in Nablus, they would have taken my two older sisters.

Upon my release three weeks later, I was given just two or three days to leave the country and told never to try to return. I walked out of the prison and many people recognized me. One taxi driver saw me and called Shadia’s home to tell her I was released. He elaborated that I was on my way home to take a shower and then go see her. He was right; that was exactly what I did. That was the beauty of our hometown. The fact that I only had three days before I had to leave prompted us to arrange for an official engagement, which, according to Muslim law, was a marriage contract. On September 5, 1970, we had the katb kitab in a small celebration with family and friends that was arranged at Shadia’s home. Two days later I left Nablus for Amman, where I planned to stay with my brother Faisal. When I arrived, however, I found that he and his family had left for Syria, because the Jordanian government was carry- ing out operations against the Palestinian Liberation Movement. That was the Black September war when many fighters were killed; others were arrested, and many fled across the border to Syria. 5 I stayed with our friends and neighbors until the war ended and my brother and his family returned. Shadia visited Amman from time to time, as her grandparents lived there.

A Delayed Wedding

I had communicated with my brother Adli, who was a professor of chemistry at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, about my chances of immigrating to the US. He offered to apply for me and my wife to immigrate as relatives of a citizen. At the same time, we applied for an immigration visa through the US embassy in Amman based on my academic achievements and the need for physicians in the US. The war in Vietnam had caused a shortage of doctors.

While waiting in Amman for visa approval, I worked at the Ministry of Health as a coroner, as it was the only position available to me. When, in April 1971, we received the approval for immigration, we set April 17 as the date for our wedding. Meanwhile, as Adli advised, I applied to Borgess Hospital in Kalamazoo, Michigan. I sent an inquiry to the director of medical education, Dr. Springgate, who informed me that their policy was to grant a position only after an interview in person. (Much to his surprise, I showed up in person few months later.)

I asked the family to apply for a visiting permit for me to attend the wedding in Nablus. At the time, my cousin Hamdi Kanaan was the mayor in Nablus; he applied several times for a permit for me to visit, even posting a large bail to allow me a twenty-four-hour visiting permit. But on the morning of the wedding, the rejection came from the military headquarters in Jerusalem. Shadia was alone on our wedding day; the party took place in my absence. The next day, I met Shadia and her mother on the bridge that separates the West Bank from Jordan. We checked into the Hotel Intercontinental in Amman. The situation at that time was very tense because the Jordanian government had imposed curfews on sections of the city for a week at a time, and they were conducting house-to-house searches for weapons, so the different neighborhoods were isolated from each other. Nonetheless, my brother managed to have a small, special party for us at his house. Shadia wore her wedding dress, and we had our delayed wedding. We planned to leave for the US in early May, spending a few days in Cairo on our way to show Shadia where I had lived as a student. Prior to our departure from Amman, I asked Shadia’s uncle Khalid, who had friends at the Egyptian embassy, to make sure that we would be allowed to enter Cairo. At that time, relations between the Arab National Movement and Egypt were poor, as the Egyptian intelligence accused the movement of plotting against Nasser during the war in South Yemen.

The embassy personnel gave us the green light to travel to Cairo. Upon arrival, however, Shadia was allowed to enter the country, but I was not. Of course, we both stayed in the airport hotel under guard until the next day, when we boarded a plane to London. We stayed in London for three days and flew to the US on May 4. My brother Adli, his wife Carolyn, and their children Tim and Mona were waiting for us at the Detroit airport.

We continued our journey together in the US for the next fifty years.

Internship and Residency

The first thing I did after we settled in Kalamazoo was to call Dr. Springgate, the director of medical education at Borgess Hospital, for an interview for an internship. My call was a surprise for him—he told me later on that he never expected it. His previous response mentioning the requirement of an interview had been a polite rejection of my request. Apparently the hospital had had bad experiences with foreign graduates in the past, so it was decided not to accept foreign interns anymore.

We made an appointment for a few days later. Dr. Springgate invited Dr. Tucker, an oncologist, to join the interview with him. It was an interesting interview. After thoroughly grilling me on my medical knowledge, they asked several questions about how I would treat Jewish patients or deal with Jewish personnel in the hospital, including physicians.

Two days later I was offered a position, and Dr. Springgate asked me if I was willing to start on June 1 rather than July 1, which was the official starting date for the year’s new interns. I accepted. Dr. Springgate told me afterward that I had given him no reason to reject my request for a position as an intern. He also mentioned that he was happy that I was one of that year’s interns.

I must say that it was challenging for me to adjust to the different culture and the new system. I had no difficulty obtaining history from patients; the problem was how to dictate the history of the physical. Initially, I would write it down and make sure it was accurate, and then I would dictate. It used to take me more time than the other interns, of course, but gradually I was able to dictate directly.

I rotated through service monthly, but because I was interested in neurology, I spent two months in the neurology service. Dr. Russell Mohney had a demanding practice as the only neurologist in the area. He was very busy seeing patients in the office, in the emergency room, and in the hospital. He used to go home for dinner with his family and return to the hospital for consults and to make rounds on his inpatients. He would call me to meet him at night in the hospital and I would comply—this was not a normal expectation for an intern. I learned a lot under his tutelage. We established a special relationship that lasted until his passing in February of 2020.

One story Russ enjoyed telling over the years was about the time we invited them to dinner at our apartment. Shadia prepared a special dinner for eight, thinking that we would be hosting Russ and his wife Cleora and their four kids. She had to borrow chairs from our neighbor across the hall. We were disappointed when just the two of them showed up alone without their kids; for their part, they were surprised that we had meant to invite the entire family, the Arab way.

After my internship, the next step was for me to find a position as a resident in a neurology program. I applied to several places with the help of my sister-in-law Carolyn, who typed more than a hundred applications for me. I was disappointed and discouraged because I was unable to secure a position. One day, Russ noticed that I was anxious and uncomfortable and asked me what was going on, so I told him. The next day he let me know that he could arrange a residency position for me in the Mayo Clinic, where he had trained; or at Wayne State in Detroit, where he had graduated; or at Indiana University in Indianapolis, where he had connections. I told him that I needed his help to choose, as I had no idea about any of these places. He patiently explained to me that the Mayo Clinic was a major referral center where I would be exposed to more specialized cases. In his opinion, Detroit was the best place to learn because of the patient population; however, he said Detroit was not a safe place. He advised me to go for an interview at Indiana University. They had a general hospital in the city, a university hospital for referrals, and a veterans’ hospital. He made arrangements for me for interview. I found out later that he had secured a place for me in advance and had persuaded Dr. Dyken to offer me a position, but he did not tell me that.

It was a most interesting trip to Indianapolis. Shadia and I stayed at the student union on campus. Although we had a car—a beautiful gold Camaro—we took the bus because we were not used to driving on the interstate, and Shadia was seven months pregnant with our first child. The interview went well, and I was offered the position. It was a happy day. Russ told us that they had asked him if he would take me as a partner when I finish. He had said yes, and that was the determining factor in me being offered the residency. Interestingly, Dr. Dyken also offered me a staff position at the university when I graduated.

Residency in Indianapolis

My residency program was confirmed for the three years from 1972 to 1975, so after I completed my internship year in 1972, we moved to Indianapolis. Russ asked me to return to Kalamazoo as a partner in his neurology practice after I finished my training.

I started the residency program at Indiana University in July 1972. It was a great program. One of the more interesting features that had an impact on my future practice was a two-month dedicated course in neuroanatomy that involved no assignments other than just studying. I mention this because at that time the neuro CT scanner was under development. This course was conducted under the supervision of Dr. Dyken, the head of the program. He had the brain dissected in order to scan slices with the CT scanner. He explained that this technical modality was a scientific revolution, and we would need to have a thorough understanding of it for our future practice.

Back to Kalamazoo

Through hard work and continuous study, I became certified as a surgeon by the Michigan Medical Practice Board in 1974 and graduated from my residency in neurology at Indiana University in 1975. (Later, in 1983, I received my certification in neurology from the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurosurgery.) I then returned to Kalamazoo to join Dr. Russ Mohney in his practice. This city would be our home from then on. Our second son, Khaled, had been born in Indianapolis in March of 1973, but our other sons were born in Kalamazoo: Nidal, the youngest, in 1979, Hilal in 1976, and Samer in 1972.

Russ was a visionary. He was following the technical development of the head scanner closely, and even traveled to London to inspect the device (it was called the EMI scanner back then, because it was produced by the company Electrical and Music

Industries Ltd.). He signed a contract to have the scanner brought to Kalamazoo. His reputation at the hospital and his leadership helped to have the scanner installed at the hospital. There were no neuro or radiology programs offering special training for the CT scan back then, so Russ and I traveled to Utah to get training. When he offered to partner with the radiology group in town to use the scanner, they insisted on exclusive rights to have it in the radiology department, and refused to cooperate with the neurology service. Finally, the Borgess Hospital board of directors decided to have it installed in the neurology department. This was in the summer of 1975, the year I joined Russ’s practice. The intensive neuroanatomy course that I had taken in Indianapolis was of great benefit, as it allowed me to interpret the images. I also took time off to study and attend meetings to learn a lot more about CT imaging.

A Private Practice for CT Scans

The CT scanner was a revolution and a turning point in the practice of neurology. It drastically improved the limited exams that had been available to us to study brain pathology in clinical practice. Back then, each scan took more than a minute for each slice of the brain; the units these days take only two to three minutes for the entire exam.

Our practice grew over the years and became a major referral center in southwest Michigan. We opened clinics in several hospitals in the region, and we constantly received patients from hospital emergency rooms. My relationship with Dr. Mohney became stronger over time. After the second year I became a full partner, and Russ offered for me to take over the management of the practice. He must have found something special about me to allow me to expand the practice with his help. I asked him later about the reason behind his confidence in me. He said that he was sure that I would be fair and respectful to the employees.

A few years later, the body CT scan was developed and became available for clinical practice. Changes in the hospital administration at the time allowed the radiologists to have the body scanner in the radiology department. We were denied access to the new scanner and the ability to study the spinal cord, which was an important part of neurology and neurosurgery practice. That change in administration policy prompted us to think about having a body scanner as part of a private practice that would be shared with the neurosurgery department. I made a presentation to the two groups, proposing to acquire our own scanner in our office across the street from the hospital. I took charge of the project from A to Z, studying the regulations as well as developing the finance plan, which was approved by the two groups. (In 2007, neurosurgery withdrew its ownership interest.) Fortunately, Dr. Mohney owned a building across the street from the hospital, and he gave the green light to proceed with the project. The two practices merged under the title Kalamazoo Neurological Institute, and the scanner was installed. Two years later, following another change in hospital administration, the new administration approached us about a partnership in our scanner. We accepted, as we had a special relationship with the new administration. That partnership benefited both our private practice and the hospital.

The MRI Revolution

The second revolution in imaging was the invention of the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, which came ten years after the development of the CT scan in 1975. In 1985, we added a partner to our group, Dr. Illydio Pallachini, who would be a great asset to the MRI program. Our group brought the MRI to Kalamazoo in 1986 as part of our practice. It was one of the first units in the state of Michigan (the other three were installed at University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, at Michigan State in Lansing, and at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.)

After we obtained the certificate of need from the state of Michigan, we had the MRI unit installed as part of our partnership with the hospital. Fortunately, Dr. Mohney owned a house adjacent to the building where the CT scanner was housed. He gave the green light to tear down the house and erect a new building for the MRI next to the building with the CT scanner. The now-expanded facility, which was named KNI (Kalamazoo Neurological Institute), became a well-known imaging center in the region. Later, in 2012, I was honored to have the building named the Kanaan Imaging Center.

In order to control the installation of medical equipment and to keep medical expenses contained, the state of Michigan developed rules that allowed mobile MRI units to serve multiple hospitals. Aided by our good relationships with several hospitals in Michigan, we initiated the first mobile program to serve twenty-two hospitals from the Detroit area in the east all the way to the extreme west side of Michigan. This program was the first to be accredited by the Joint Commission. 6

As time went by, a new building was erected on the Borgess campus to host our MRI unit in connection with the hospital. We eventually added two units to this hospital site and two at our KNI office, as well as mobile services in other locations in Kalamazoo. Our imaging center became a symbol of excellence, as we established the highest quality imaging systems and hired an outstanding staff of technicians, nurses, and support staff. All were recognized as the most professional, disciplined, and dedicated teams, whether at the fixed sites or the mobile units.

I had the honor of being part of this project since the beginning, and I am proud of what we achieved. Our success was due to our dedication and discipline and our adherence to the mission of providing quality service to our patients. Finally, after thirty-seven years of serving as CEO of the organization, I felt it was time to step down. I officially retired as of September 1, 2020.

Azzam’s wife, Shadia, wrote the remainder of this account of Azzam’s life.

Although Azzam devoted long hours and enormous energy to his work, the compass in his life was always Nablus and Palestine. Palestine gave a sense of belonging to family and support for our people in various ways. Social solidarity involved charitable donations to civil institutions, such as the Red Crescent, the Nablus senior center, the orphanage, and the center for the blind, as well as ongoing university scholarships for Palestinian students both privately and through the Al-Birr Society. Azzam’s support for Al-Ittihad Women’s Hospital in Nablus was one of his priorities. He dedicated the renovation of the women’s wing at Al-Ittihad Women’s Hospital to the soul of his mother, Mrs. Rabiha al-Nabulsi Kanaan. He also made donations to the general budget and maintenance of the hospital every year.

Our social activities focused on raising awareness of Palestine through local media outreach, giving lectures, hosting speakers, and arranging meetings and seminars. Through these avenues, we made an effort to educate people on the issue of Palestine and clarify its legitimacy, spread positive thought, and engage in interfaith dialogue to convey the sanctity of the Islamic religion and its sublime message to humanity. This spirit was and will remain firmly established in the souls and minds of our four children and grandchildren, God willing.

Azzam was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), in May of 2019. He fought the disease for the next twenty-two months, cared for at the University of Chicago hospital. Even during these difficult months, he did not stop monitoring events in Palestine for a moment. In January 2021, he was put on a new experimental treatment regime. When it became clear that even this would not alter the course of the disease, he informed the doctors that his final wish was to die and be buried next to his beloved mother in Nablus, Palestine. And so it was.

After a long and beautiful journey across the seas of life, the ship returned to Palestine and dropped its anchor for him to bid farewell to his beloved city, Nablus, which had always been his compass, his hope, and his legend. Azzam passed away on March 3, 2021.

He devoted the last eight years of his life to his book on the history of Palestine. This book, which gives an account of Palestine’s history through the last ice age, the Stone Age, and the Bronze Age into our modern era up to the year of the Nakba in 1948, is an important historical touchstone. As I write this, it is in the final stages of revision and will be published, God willing, in the near future.

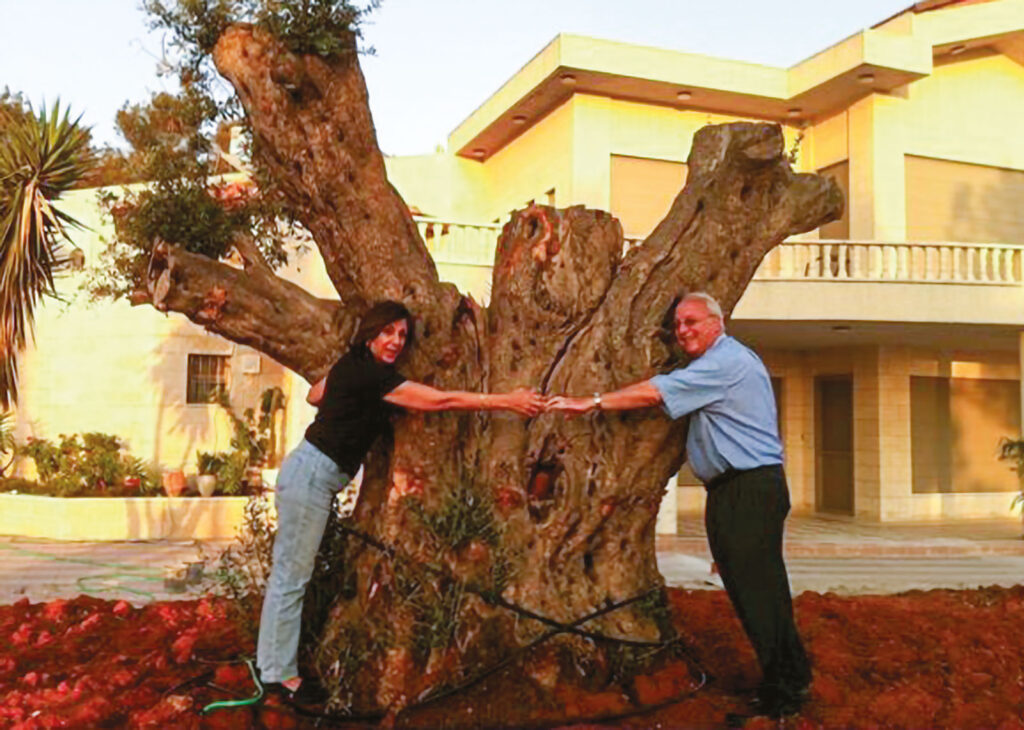

The legacy left by Azzam Kanaan stems from his keenness to remain steadfast in the land, as this is the most powerful weapon against the occupation and the policy of transfer, whether forced or voluntary. This conviction led him to build a house for our family on a farm on Jarzeem mountain in Nablus. He planted hundreds of olive trees, peach trees, apricot trees, cherry trees, and grapevines, hoping to return there to spend his retirement years. His goal was to provide work for some locals, even if simple, keeping everyone rooted in the land.

The most important part of his legacy was his last mission: to build a basic school serving the children of the old city of Nablus on the site of his ancestral home, which had been destroyed by the Israeli occupation in the invasion in 2002. (That invasion also demolished the ancient Kanaan soap factory belonging to my own grandfather, Hajj Saeed Daoud Kanaan.) His belief in the sanctity of education and its importance in creating an educated, productive generation of Palestinians motivated him to establish a trust and allocate the funds required for the school’s construction.

The school will see the light in the 2024 academic year, God willing.

Azzam’s legacy will endure through his book on the history of Palestine, and through the Azzam Kanaan Middle School for Girls in the old city of his beloved city of Nablus, and through the kindness with which he suffused the world.

May he rest in peace.

SHADIA KANAAN

April 2024