The Ptolemaic and Seleucid empires striving for control of Judea, Samaria, and Phoenicia. The revolt of the Maccabees and the emergence of the Hasmonean dynasty. Fighting among various factions for control of Jerusalem. An account of Palestine under Roman rule, including the Palestinian resistance and the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem. The story of the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

The Ptolemies and the Seleucids

In 301 BCE, Judea, Samaria, Phoenicia, and the entire coastal plain were captured by the forces of Ptolemy, an Egyptian general who had Egypt as his power base. The Ptolemies, one of the four powers that emerged after the breakup of the Macedonian empire, controlled Palestine for most of the third century BCE. They integrated Palestine’s towns and cities into the Greek culture. Hellenism had been penetrating the Near East for many decades prior to Alexander’s invasion of the region. Northern Palestine’s coastal cities, which were part of the Mediterranean trade routes, were affected the most. Other cities located on the main inland trade routes, such as Gaza and Petra, were also influenced by the Greek culture. Jerusalem had little contact with the Greeks, as it was a poor city lacking the raw materials needed for the development of industry; it was also far from the trade routes.

The Ptolemies, like most of the previous imperial forces who ruled Palestine, did not interfere in the local affairs of the different Palestinian regions. They introduced an efficient administration that was flexible enough to treat each region of their kingdom according to its particular social, economic, or religious situation. They appointed their own governors and installed garrisons in the different cities, but left people to follow their own traditions. Some parts of Palestine were crown lands ruled directly by royal officials. In addition, Greek colonists established their own cities (polis) modeled after the democratic Greek republics in several towns such as Gaza, Shechem, Marissa, and Amman, which were self-governing. Greek soldiers, merchants, and entrepreneurs took advantage of the opportunities that opened to them in the east. At the same time, the local people were eager to learn the Greek language and were attracted to Greek culture.

The Hellenistic culture was secular, advocating the separation of the government from religion. Apparently, the people of Jerusalem initially opposed this secular concept; however, the city was gradually dragged into the Greek world, and by the end of the third century BCE, Jerusalem’s citizens had begun to acquire Greek education and were giving their children Greek names. 58

During the reign of Ptolemy II (282–246 BCE), a Jerusalemite called Joseph was given the job of collecting the taxes of the whole province of Syria. For over twenty years he was one of the most powerful men in the country. Joseph was able to introduce the high finance of the Hellenes into Jerusalem, becoming the first Jewish banker. He belonged to the Tobiad clan, who would not submit to the exclusive cult of Jerusalem and were interested in establishing relationships with foreigners. The Tobiads became the pioneers of Hellenism in Jerusalem. Other segments of the population opposed Hellenism and remained determined to maintain the old laws and traditions. The Oniads, a well-established priestly family, led the camp opposing Hellenism and adhering to the old laws and traditions.

In 219 BCE, the Seleucid king Antiochus III started a military campaign to control the province of Syria. The war between the Ptolemies and the Seleucids lasted for several years, during which Jerusalem was subjected to a long, harsh siege. The war ended in 200 BCE with the surrender of Jerusalem to the Seleucid forces. The conservative faction in Jerusalem, under the leadership of the Oniad family, supported the Seleucids and helped them in their wars against the Ptolemies, hoping to gain control of Jerusalem. The Seleucids followed the same policies as the Ptolemies in governing the Palestinian population. In 200 BCE, Antiochus III drew up a special charter, the Charter of 200 BCE, granting the inhabitants of Judea special rights, and made a special arrangement for the temple in Jerusalem to insure the purity of the shrine. He acknowledged the Torah as the law of the land and gave the Jewish priest Simon II great agency in Jerusalem’s affairs. The Seleucids likewise established special arrangements for the Greek cities, the military colonies, and the crown lands.

The office of high priest of the temple in Jerusalem was hereditary, passed down in the same family since the beginning of the Persian rule of Palestine. However, the king had the right to confirm the appointment. This tradition continued during the rule of the Macedonians and the Ptolemies, and was also followed by the Seleucids. Simon, the high priest, played a major role in Jerusalem’s politics. He acted as king and priest of Jerusalem.

The Seleucid kings were known for their encouragement of urban development, a policy that advanced the process of spreading Hellenism in Palestine. A group of men from Jerusalem organized themselves as “the Antiochenes in Jerusalem”; they wanted to be able to establish a Greek school (gymnasium), and to be separated from the authority of the high priest. The Antiochenes felt that to achieve their goals, they needed to replace the high priest Onias III, who was known to be “a zealot for the laws”—that is, the Jewish law, the Torah. So in 174 BCE they approached the new Seleucid king, Antiochos IV, asking him to depose Onias and appoint his brother Jason, who was receptive to their plans. 59

Jason, the new high priest, was not a “zealot for the laws” like his brother, and was not interested in following Jewish law. He was hoping that Jerusalem would become a polis (Greek city). He even went further by asking the king to revoke the Charter of 200 BCE that gave special rights to Judeans. Some priests, merchants, and craftsmen welcomed the changes and became involved in the gymnasium activities. They were hoping that a more open society in Jerusalem would bring prosperity and economic growth. In their mind, there was no advantage to the Jews being separated from their non-Jewish neighbors. Initially, the “Hellenizers” did not face significant opposition from the Jews in Jerusalem, and when King Antiochos visited Jerusalem in 173 BCE, Jason led the people in applauding the king through the streets in a torchlight ceremony for the occasion. 60

Jason, the high priest, was trying to maintain a difficult balance between the Jewish beliefs and Greek ideas. He adopted a centrist position between the traditionalist Jews and the Hellenizers. This position did not please the Antiochenes, who became impatient with his tactics. Disgruntled that the Hellenization process was not proceeding as fast as they wished, they sent a delegation to King Antiochos IV asking him to replace Jason with Menelaos, a priest who was willing to accelerate the Hellenization process. Antiochos IV acceded to their request; he removed Jason from his office and appointed Menelaos, who was not a member of the Oniad family, as the new high priest of Jerusalem. Jason left Jerusalem and took refuge across the Jordan with the Tobiad family. 61

In 171–170 BCE, Antiochos IV was involved in a two-year war with the Ptolemies of Egypt, and was falsely reported to have been killed. Jason returned to Jerusalem and attempted a coup, forcing Menelaos and the Antiochenes out. When Antiochos IV returned from Egypt in 169 BCE, he immediately seized Jerusalem, looted the temple, eliminated Jason’s supporters, and reinstated Menelaos. He then built a new fortress called Akra, which overlooked the temple enclosure. These actions were followed by issuing an edict revoking the Charter of 200 BCE and disallowing the practice of the Jewish faith, including the Sabbath rest, circumcision, and the observance of the purity laws. As a result of this edict, the temple was dedicated to “Zeus Olympios, the God of Heaven” a title that could be applied to Yahweh or any other high god. This did not mean that the Jews were forced to worship the Greek deity; it simply meant that the temple was open for all religions, and both Jews and pagans could offer their sacrifices in the sacred shrine. 62

As Menelaos was reinstated as high priest, the Hellenizers once again gained full control of Jerusalem, which continue to develop as a Greek city. A new governor, Apollonios, was appointed; he was described as a revenue official interested in collecting more taxes. The transformation of the temple outraged the traditionalists, especially when the new administration decided to enforce the reformed religious practices on the general population outside the city. The most significant response against the new reforms came from the Maccabee family, who resided in the countryside. Mattathias, the head of the family, was an influential local priest whom the reformers wished to win to their side. He had not been involved in the conflict between the reformers and the Oniad family in the period between 174 and 167 BCE. However, when the Hellenizers began to impose their reforms in the countryside, Mattathias’ anger erupted.

The Maccabean Revolt and the Hasmonean Dynasty

The Hellenizers, under the leadership of Menelaos, started their campaign of enforcing the new reforms in Judea’s countryside, after they had full control of Jerusalem. As part of this campaign, a royal enforcer came to Modiin, where Mattathias and his family resided, to oversee a regular sacrifice conducted at the altar according to the new regulations. A verbal exchange took place between Mattathias and the royal officer, who was not armed or protected by guards. The exchange ended with Mattathias and his sons murdering the officer and destroying the altar. This incident was the start of a revolt in which Mattathias, his sons, his followers, and a group called the Hasidim fled to the hills and waged a war against the Seleucids, the high priest, and the Hellenizers. They started what can only be described as a brutal terrorist campaign. They targeted the altars, destroying them and killing the worshippers. They also forced circumcision on Jewish boys who had not been circumcised before. People who did not accept their authority were driven out from their homes. By the time Mattathias died in 166 BCE, the Judean countryside was fully controlled by the rebels. 63

In 166 BCE, when Mattathias died, his son Judah, nicknamed Maccabeus “Hammer-Headed,” succeeded him as the leader of the rebels. He followed the same policies and tactics, and strengthened his control over the countryside. He presented his movement as a religious rebellion aimed at restoring the purity of the temple and adhering to the teaching of the Torah, thus expanding his popular support among religious Jews. He also emphasized that the revolt was an independence movement aimed at ending foreign oppression. His forces, the Maccabees, were not professional soldiers, but brave fighters highly motivated by their religious beliefs and patriotic feelings. Judah was an intelligent and inspirational commander of his guerrilla forces. This was clearly proven in the battlefield, where he faced professional Seleucid soldiers who had undergone extensive military training and were well equipped.

Antiochos IV sent a Seleucid force headed by the governor of Samaria to suppress the revolt and eliminate Judah and his forces. Judah and the rebels won an unexpected victory, enhancing his position within his army and strengthening the people’s support for his movement. 64 A second Seleucid expedition against Judah also resulted in a victory for Judah and his forces; they killed many of the invaders, including the Seleucid leader. 65 These victories established Judah as a formidable commander with great talent and military sophistication, and demonstrated that the Maccabee army had developed a significant degree of skill and professionalism.

In 166 BCE, when these two battles took place, Antiochos IV was preparing his main army to march east to confront the Parthians. He made his son Antiochos V, who was nine at the time, joint king, and left him in Antioch under the protection and guidance of his loyal minister, Lysias, who was also charged with the responsibility of suppressing the revolt in Judea. Lysias appointed two commanders to head a new force to deal with the rebels. Judah again used strategy and an ambush attack to defeat the Seleucids. Despite these victories, however, the Maccabean army was still not capable of advancing to the lowlands. They were only able to carry out limited surprise attacks or plan ambushes.

In the summer of 164 BCE, Lysias planned a massive attack against Judah’s forces; however, he had to suspend his plans and return to Antioch upon receiving news of the death of Antiochos IV. He had to secure the ten-year-old Antiochos V, who was still in Antioch. Judah took advantage of the situation and marched into Jerusalem, which was not fortified. However, he was not able to take Akra, the fort overlooking the temple. After celebrating his victory in taking Jerusalem, he intensified his guerrilla attacks south of Judea in the Idumaea region, in the Transjordan Plateau against Ammanitis and Galaaditis, and in northern Palestine in the Galilee area. These attacks were preemptive defensive moves and looting expeditions; in certain locations they were also punitive measures against Hellenizer Jews who were opposing the Maccabees. Judah’s forces committed many crimes against Palestine’s population, the worst being the massacre of the Tobiads, a family of moderate Jewish Hellenizers who had built a Jewish temple in Transjordan not far from el-Amir in Iraq. Many other Jews were killed and their homes were destroyed.

All Judah’s raids failed to secure further territory beyond Judea. Taking over Jerusalem was meaningless as long as Akra was still in the hands of the Seleucids and the Hellenizers. To secure Akra, Lysias returned to Palestine, marched toward Beth Zur from Idumaea, which was taken after a short siege, and then continued toward Jerusalem. His forces achieved a decisive victory against the Maccabees; however, he had to return to Antioch in July 162 BCE to face Philippos, the commander of the Seleucid forces in the east. As soon as he drove him out of Antioch, he faced another contestant, Demetrios, who was supported by the Romans. Demetrios succeeded in killing both Lysias and Antiochos V, and then claimed the throne.

Demetrios sent massive forces to Palestine under the command of Bakchides, who used a new route to reach the Judean plateau through the Jordan Valley east of Judea. Bakchides was an experienced commander familiar with the Maccabees’ tactics, which allowed him to win a decisive victory, inflicting many casualties among them, including their leader, Judah, who was killed on the battlefield. Bakchides gained complete control of the province; his forces wiped out the Maccabees’ supporters and ended the terrorist campaign that Mattathias had started. Jonathan, who succeeded his brother Judah as the Maccabees’ new leader, settled down and stopped fighting.

Bakchides set a defensive program aimed at strengthening the Seleucids’ grip on Judea by fortifying several cities to control all communication routes: Beth Zur, which controlled the approach from the south; Beth-Horon, at the upper end of the pass; Bethel, at the junction of several routes north of Jerusalem; Ammaus, at the entrance to the hills; and Tekoa, Jericho, and Gezer in the lowlands to the east and west. In addition, he strengthened Akra, and housed hostages collected from the main Jewish families there. 66

The death of Judah put an end to the first stage of the revolt, the guerrilla war. The Maccabees’ successes in this war were credited to Judah’s personality as a charismatic fighter and his ability to wage guerrilla warfare effectively, as well as the motivation of his brave, dedicated fighters. But the defeat of the Maccabees by Bakchides did not put an end to their movement; rather, it was the beginning of a new stage under the leadership of Judah’s brothers, Jonathan and Simon, who adopted new strategies and tactics.

Jonathan forged a peace agreement with Bakchides in which he acknowledged Seleucid authority; however, he occasionally carried out attacks against his Jewish opponents using the same tactics of murder and beatings aimed at punishing the “sinners” and intimidating the general population. But when the Seleucids had to focus on larger threats, he saw his opportunity to carry out a purging campaign openly.

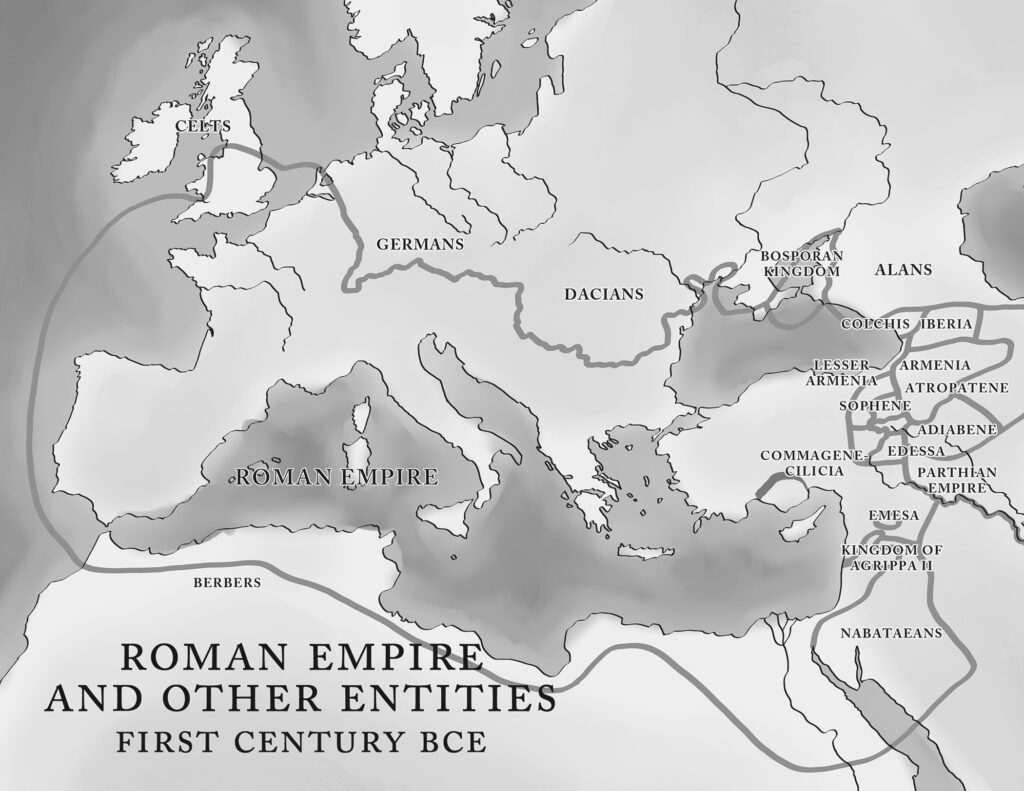

Between 154 and 140 BCE, the civil wars between the various Seleucid contenders for the throne gave the Maccabees the opportunity to gain autonomy and expand their authority over Judea. They mastered diplomacy and the art of negotiation to extract more concessions. They also established channels of communications with the Romans, who at the time did not have any plans to extend their empire beyond Greece; however, they had been keeping an eye on events in Asia Minor, Egypt, Syria, and Palestine, as well as Persia, preparing themselves for the future. The Maccabees were occasionally involved in the Seleucid civil wars, at times sending troops to side with one faction or another. They also managed to expand their territory to include strategic Palestinian cities such as Beth Zur, Joppa, Gaza, Ashkelon, and Ashdod, and succeeded in removing most of the fort garrisons. Their expeditions reached Galilee in the north and Transjordan in the east. During these years, they also continued their purging missions by eliminating or controlling the Jewish Hellenizers.

In 142 BCE, the Seleucid king Tryphon, who had taken the throne in 144 after overthrowing Demetrios, invited Jonathan to Ptolemais to discuss the relationship between the autonomous Maccabee state and the Seleucid Empire, and held the Maccabee leader captive there. Jonathan’s brother Simon summoned a Jewish assembly in Jerusalem for the purpose of having himself elected as the temporary leader of the Maccabees while Jonathan was in captivity. In 141 BCE, Tryphon killed Jonathan, and Simon became the permanent leader. The people of Jerusalem later elected Simon as high priest. The election of Simon as high priest by the people, instead of being appointed by the king, marked the start a new stage of the Maccabees’ movement: the era of Judea’s independence. 67

Jonathan had played a major role in the establishment of the Maccabean state. The Maccabean movement passed through three major stages. During the first, the rebellion led by Judah, which was characterized by guerrilla warfare aimed at punishing “sinners,” the rebels were able to defeat the Seleucid armies twice. However, the third confrontation between Judah and Bakchides ended up with a decisive victory for the Seleucids and the end of the revolution. Judah was dead, the Maccabees’ supporters were wiped out, and the terrorist campaign that Mattathias had started was over. Garrisons were established in several fortified towns to ensure security in Judea. 68 The second stage of the Maccabean movement was established by Jonathan, who is considered the founder of the Maccabean state. Jonathan established a professional army and was able to win a few victories against the Seleucid forces, preventing them from invading Judaea and succeeding in removing most of the fort garrisons. He established himself as the king and high priest of Judaea. As he continued his purging policy, he managed to build a friendly relationship with the moderate Hellenizers. He succeeded in building an autonomous state by extracting concessions from successive Seleucid kings. The Seleucid king Demetrius, who was occupied with his wars against the Parthians and the civil war against Tryphon, recognized Judea’s independence. After Jonathan’s death, Simon expanded his territory by capturing Gezer, which had a strategic location at the west edge of the hills, overlooking the coastal cities; at the same time, it was the gateway to the east. The next move was against Akra, which was purged after it fell to his forces. Simon refortified all the cities he captured, including Akra, and devoted his time to establishing a hereditary monarchy. He also devoted time and resources to erecting palaces whose design was similar to that of the Hellenistic cities. This was followed by sending envoys to all the states in the eastern Mediterranean, as well as to Rome. He then erected a stele, in the best Hellenistic style, on which he inscribed the Maccabees’ achievements. 69

During the initial period of his rule, Simon was fortunate that Demetrios was engaged in his wars against the Parthians and Tryphon. When Demetrios was killed in the east, his brother, Antiochos VII, took over. Antiochos was an accomplished soldier and a clever politician. After he defeated Tryphon, he reorganized his army and began preparing to regain Seleucid control over Judea. A limited war erupted between Judea’s forces and Antiochos’s army; this ended with a peace agreement in which Simon acknowledged that his state was part of the Seleucid kingdom.

In February of 134 BCE, Simon’s son Hyrkanos succeeded his father and was elected in Jerusalem as the high priest and the new leader of the Maccabees. His election to these posts marked the beginning of the third stage of the Maccabees’ movement. Hyrkanos was the king of Judea as well as the high priest. Holding both positions gave him complete control over all state affairs. His first mission was to defend Judaea against the forces of Antiochos VII, who marched to Palestine to put an end to the Maccabees’ rule. Hyrkanos was prepared for a long siege, but it lasted almost a year, and at the end he had to acknowledge the authority of the Seleucid king over Judea as a vassal state, and was forced to pay a large tribute to the king. He also agreed to send troops to fight the king’s enemies when needed. In fact, Hyrkanos participated in a Seleucid war against the Parthians in 131 BCE. The death of Antiochos VII in 129 BCE released Hyrkanos and Judea of their obligations, however, and Judea became an independent state once again. 70

In 129/128 BCE, this state was limited to the hills centered on Jerusalem and some neighboring lowlands. Between 128 and 122 BCE, Hyrkanos expanded his territory in two directions: to the east across the Jordan River, and south toward Idumaea. He first captured Medaba, a small city across the river, close to Mount Nebo on the old trade route. Most likely he targeted this site for potential trade revenue. He then targeted a smaller village, Samoga, northeast of Medaba, which, being located at the highest point between Medaba and Philadelphia (the site on which Amman, Jordan, was built), served as observation post. Hyrkanos avoided the Greek city of Philadelphia. The Nabataeans who dominated the lands east of Philadelphia and southward as far as Petra and the Gulf of Aqaba were strong, autonomous rulers who were too powerful for Hyrkanos to take on.

During this period, between 128 and 122 BCE, Hyrkanos carried out similar military expeditions south of Judaea in Idumaea. The Idumaean lands had been the route through which Judaea had been invaded several times, and the Idumaeans had assisted the invaders who were crossing their lands toward Jerusalem. Expanding Judaea’s territory south of the fortified town of Ben Zur was important to Hyrkanos’s defense strategy. He attacked and captured Adora and Marisa in northern Idumaea, aiming at setting a wider defensive line to protect Judea from further attacks. He also forced the Idumaeans to convert to Judaism.

The Shechem (Nablus) area was another route used by invaders to reach to Jerusalem. During the same period, Hyrkanos carried out a raid against the Samaritans in Shechem and at Mount Gerizim, the site of their temple. The purpose of the raid was apparently to destroy the Samaritans’ temple, which was considered a competitor to Jerusalem’s. Both Shechem and Gerizim were captured and the Samaritans’ temple was destroyed, but the region was not annexed, as the Maccabees were unable to keep a strong garrison. Many Samaritans fled to Samaria (now Sabastia), the capital of the district. Hyrkanos limited his expedition in this area to just the destruction of the temple, which was considered a challenge to the Maccabean ideology. He avoided the Greek city of Samaria, the capital of the district, which would have required a strong force to capture. His aggression campaign against the Samaritans was similar to his predecessors’ raid against the Tobiads and their temple in Iraq el-Amir.

The years between 121 and 113 BCE were a period of relative peace for the Seleucids, and Hyrkanos remained quiet. As the Seleucid civil wars erupted again around 113 BCE, Hyrkanos became active again. The Seleucids suffered greatly in their war against Parthia, and the civil wars also contributed to the decline of the kingdom’s military power. The city of Samaria was the next target for Hyrkanos.

Samaria was a Greek city, with Jews and Samaritans among its inhabitants beside the Greek ones. As a justification for attacking the city, Hyrkanos accused the Samarians of taking the side of the Samaritans against the Jewish inhabitants. The Judean army failed to capture the city at its first attack, so Hyrkanos subjected the city to a long siege. Two Seleucid factions tried unsuccessfully to save the city. Both Seleucid armies were ambushed by the Judean army, and they were forced to retreat. In the end, the city was sacked, the site was razed, and a stream was diverted to run over it. The surviving inhabitants were sold into slavery. Capturing Samaria allowed the Judean army to advance north toward Galilee.

Hellenism and the Maccabean Revolts

It is important to note that in the beginning, the Maccabee family had not opposed Antiochene efforts to bring Hellenism to Judea. However, when the Seleucids introduced the new religious reforms which revoked the Charter of 200 BCE guaranteeing the purity of the temple in Jerusalem, Mattathias, the head of the family, had finally revolted. The revolt was against polytheism, religious persecution, and foreign control, but not against Hellenism and Hellenistic culture. As the Maccabees controlled Judea and established their Hasmonean state, they restored the purity of the old religion and removed the Hellenic influence. At the same time, they were open to the Greek culture, which influenced all aspects of life in the Hasmonean state. The Hasmonean kingdom was the first monotheistic religious state in history; at the same time, it was Hellenistic. This was an important factor in the spread of Judaism. Hellenism injected Judaism with the element of anti-tribal universalism which led the Hasmoneans to abandon an exclusive ideology, and also inspired them to move toward expanding their kingdom to include all of Palestine and to convert all Palestinians to Judaism. Shlomo Sand describes the Hasmonean goals and strategy: “The Hasmonean theocracy used the sword to spread not only its territorial domain but also its religious following.” They succeeded in expanding their kingdom to include the entirety of Palestine and achieved their goal of spreading Judaism among its inhabitants through forced conversion. Mattathias’ grandson, Jonathan, added the Greek name Hyrcanus to his Hebrew name. The great-grandson of Mattathias was called Judas Aristobulus, and his son was called Alexander Jannaeus. The royal courts of Judea resembled other Hellenistic courts in the region, as did the system of dynastic succession. 71

The Fight for Control of Jerusalem

Not all the Jews shared the Hasmonean vision and policy of Hellenizing the country. Some admired what they did, but others opposed it. Initially Hyrkanos was on good terms with the Pharisees, who wanted to democratize Judaism, but a dispute erupted because Hyrkanos, as the high priest, had the power to interpret the law. The Pharisees attempted to establish their own political authority over the high priest by presenting themselves as the ones who had the authority to interpret the law. Hyrkanos did not yield to their claim, and crushed their revolt firmly. The Saducees, who came from the priestly and wealthier classes and supported the temple, were supportive of the Hasmoneans’ authority.

Upon Hyrkanos’s death, his oldest son, Aristoboulos, became the king and high priest. To consolidate his power, he imprisoned his mother and three of his brothers in the palace. He then assigned another of his brothers, Antigonos, who had shared with him the leadership of the military campaign against Samaria, to lead a new campaign in northern Palestine.

Aristoboulos died in 103 BCE, after one year in office. His brother Antigonos, who was still in northern Palestine, was assassinated around the same time. Their mother had died in prison prior to their deaths. Aristoboulos’ widow, Salome Alexandra, released the brothers from prison, and then put Alexander Iannai, the next-eldest son of Hyrkanos, forward as the new king, and apparently married him. 72

The new king, Alexander Iannai, was unknown to Judeans in Jerusalem. His father Hyrkanos had sent him to Galilee to grow up in a sort of exile. 73 Having chosen the battlefield to gain the support of the Judeans and to prove his ability as a leader, he carried out multiple military expeditions against several cities that resulted in defeat and an alliance with Queen Kleopatra III of Egypt. Between 100 and 97 BCE, Alexander was able to recruit mercenaries and skilled military staff. In 97 BCE, he carried out a successful military campaign against Gaza which, after a yearlong siege, resulted in the destruction of the city and the annihilation of its inhabitants. In 94–93 BCE, with the help of a large number of Greek mercenaries from the Greek cities in Syria, Alexander carried out another military campaign in Transjordan. He expanded his territory around Medaba and annexed Moab. Then he advanced further north, capturing Amathos and several cities in Gaulanitis (currently Golan), including Gadora (not the one in the south), Abila, Hippos, and Philoteria.

Alexander did not follow his father’s policy of forcing conquered territories to convert to Judaism. He also kept most of the cities he annexed intact; Gaza, however, was an exception. The change in the forced conversion policy was attributed to changes in internal political power in Jerusalem. During Alexander’s reign, the Pharisees’ influence declined, while the Sadducees became more influential. The struggle between the two camps became more obvious after the expansion of state boundaries and the increase in the power of the king. Opposition by the Pharisees increased and reached the level of revolt. During the Festival of Tabernacles in the temple, while Alexander was sacrificing at the altar, a crowd surrounded him and pelted him with fruit. This incident was followed by riots, which were suppressed by Alexander’s mercenaries; they killed almost six thousand insurgents. 74

When Alexander returned to Jerusalem from Transjordan, he faced strong opposition that eventually aimed at deposing him. He applied brutal measures that led to full rebellion, then turned into a long civil war that lasted over six years, during which more than fifty thousand people were killed. At the end, in 87 BCE, his forces captured the leader of the rebels at Bethoma north of Samaria. Following his victory, he executed eight hundred men plus their families. More than eight thousand men fled into exile.

Around this time, the Nabataeans in the east rose to prominence, dominating large territories and threatening Damascus. In 84 BCE, the Seleucid ruler Antiochos XII attempted a new strategy for dealing with the Nabataeans. Rather than mounting an attack from Damascus, he brought his army to the coastal plain and, with the Judean king Alexander’s permission, marched through Idumaea toward Petra. The Nabataeans allowed him to march on into the desert and then surrounded his forces with a larger army and defeated him. Antiochos was killed on the battlefield; what was left of his army took refuge in Kana, south of the Dead Sea, but they were blockaded there until most had died of starvation. 75 The Damascus city council then surrendered the city to the Nabataeans. In 82 BCE, the Nabataean king Aretas III invaded Judea and reached Adida, northeast of Lod. A humiliating peace treaty was forced on Alexander in punishment for having allowed Antiochos XIII to pass through Idumaea in his attempt to invade Nabataea.

During Alexander’s reign, Judea expanded to include most of Palestine and a significant segment of the territories east of the Jordan River. Alexander’s army lacked the skills and strength to achieve meaningful victory in open battle, however. His forces failed in any real active siege and resorted to long blockades that lasted a long time before capturing a small city. He was also fortunate that his victorious enemies did not follow up their victories, but withdrew as a result of their preoccupation with matters more urgent than capturing Jerusalem. It became clear that at some point in the future, Judea was bound to crumble when confronted with a strong, efficient, and skillful enemy.

Upon Alexander’s death in 80 BCE, his wife Salome Alexander declared herself the head of the state of Judea. Their elder son, Hyrkanos II, became the high priest; his younger brother Aristoboulos II was left as a private citizen. In an attempt to heal internal divisions, Salome brought the Pharisees back to the political scene at the expense of their rivals, the Sadducees; unfortunately, this policy led to the divisions being exacerbated. The former advisers of Alexander were targeted by the Pharisees, and several of them were assassinated. Aristoboulos sided with his father’s former staff and arranged to move many of them to forts in the countryside for their protection. The Pharisees’ influence grew significantly in the administration of the state as they became the interpreters of the law. Salome adopted a plan to rebuild the army to strengthen her power and to protect the throne. She also transferred the state’s treasury to three forts outside Jerusalem.

Between 72 and 70 BCE, the Armenian king Tigranes annexed Damascus, defeating the Nabataeans, and captured Ptolemais-Ake. He was prevented from capturing Judea when the Roman army invaded Armenia. The internal conflicts in Judea became more intense, as the Pharisees managed to gain almost complete control over state affairs. Salome became ill, and as she was dying, her son Aristoboulos prepared himself for a coup. He left Jerusalem to join the exiles, who were concentrated in twenty-two forts in the countryside, contacting them and recruiting troops. Upon Salome’s death in 67 BCE, Hyrkanos assumed the title of king—John Hyrkanos II—and Aristoboulos declared war against his brother. The armies of the two brothers confronted each other on the plain near Jericho. Many of Hyrkanos’ soldiers changed sides and joined Aristoboulos. Hyrkanos was defeated and forced to retreat to Jerusalem. He then bargained for his life and his possessions. Aristoboulos agreed to these terms, and declared himself “Judah Aristoboulos II,” king of Judea. The victory of Aristoboulos II over his brother Hyrkanos II did not put an end to the civil war. Antipater, son of Antipas, from Idumaea, a man of great wealth and political acumen, brought about an alliance of Aristoboulos’ internal opponents together with the Nabataean king Aretas III, and, eventually, Hyrkanos II himself. It was early in 65 BCE when the plot came together. Hyrkanos left Jerusalem secretly and went to Petra with Antipater. They negotiated with Aretas III, who agreed to bring his army to attack Aristoboulos II; in return, Hyrkanos agreed to cede to Aretas a large territory east and south of the Dead Sea. 76

Rome Captures Palestine-Syria

Aristoboulos was defeated by the Nabataeans and forced to escape to Jerusalem’s temple, where he was besieged. As this was happening, the Roman army under the leadership of Pompey was conducting a campaign against Armenia. Both Hyrkanos and Aristoboulos asked the Romans for help; the Roman commander decided to support Aristoboulos and advanced to Jerusalem to rescue him. He threatened Aretas and forced the Nabataeans to withdraw their forces from around Jerusalem. Aristoboulos took the opportunity to attack the retreating forces of Aretas at Papyron, near Jericho, and managed to inflict heavy casualties, killing more than six thousand Nabataean soldiers. After his victory at Papyron, Aristoboulos continued to rule Judea for over a year without Roman interference.

Pompey, who had put an end to the Seleucid Empire, moved from Antioch to Damascus in the spring of 63 BCE. During his trip to Damascus, he made several decisions concerning the different cities he passed through, removing tyrants and accepting tributes. Three autonomous kingdoms were on his agenda awaiting decisions: Iturea, Judea, and Nabataea. He left Ptolemy, son of Mennaeus, to rule over Iturea. The Nabataeans were also left autonomous after they handed over a tribute. In regard to Judea, he requested that Aristoboulos and Hyrkanos appear in his court; both were brought to Damascus. A third delegation arrived from Jerusalem at the same time, claiming to represent the nation; this was the Pharisees’ delegation, which requested the abolition of the monarchy and the restoration of the ancient rule of the priests. Pompey listened to the three delegations, as well as to Antipater. He postponed his decision until he could visit Judea in person.

Pompey marched toward Judea accompanied by all parties. On the way to Jerusalem, he requested that Aristoboulos surrender all the forts in the countryside, and Aristoboulos did so. As the Romans approached Jerusalem, Pompey asked Aristoboulos to surrender Jerusalem. Aristoboulos, who had left the march and gone to Jerusalem, came out from the city to meet Pompey, promising to surrender the city. The Roman legate Aulus Gabinius was sent to Jerusalem to take over the governorship. As Gabinius approached the city, he was denied entry by the soldiers. It was not clear whether the soldiers had done so on their own or were following instructions from Aristoboulos. Aristoboulos was arrested, and the Romans prepared to attack. The city was subjected to a three-month siege, during which the walls were battered until finally a large opening was made. The city was then assaulted, and a large number of the defenders—almost twelve thousand soldiers—were massacred.

Hyrkanos was reinstated as high priest, but not as king. The state was reduced to Judea, Galilee, parts of Idumaea, and parts of Transjordan. These territories were the areas inhabited by Jewish populations. The cities along the coast were made independent. The cities along the Jordan were joined together into what became known

as Decapolis, which included Skythopolis, Philadelphia, and Gerasa. Some sections of Transjordan in the south were added to Nabataea, and the ones in the north were added to Iturea.

Aristoboulos, his sons Alexander and Antigonos, his two daughters, and his father-in-law Absalom were taken off to Rome. During the journey, Alexander escaped and returned to Palestine, where he gathered a number of supporters. His purpose was to claim the throne and the post of high priest. By 58–57 BCE, he had amassed sufficient support to seize control of Jerusalem. The Roman governors did not prevent him from removing Hyrkanos; however, when he began rebuilding the city walls, they put a stop to it. In 57 BCE, Gabinius, who was familiar with the country, was appointed as governor. He recognized the potential threat of Alexander’s increased power in Jerusalem; at the same time, Alexander realized that Gabinius was planning to control Judea and to limit his role to just that of high priest. This development prompted him to recruit an army of ten thousand men. War erupted between Alexander’s army and Roman forces under the command of Mark Antony. Alexander was defeated and escaped to one of the forts. Alexander’s mother—the wife of Aristoboulos—negotiated with Gabinius, offering her son’s surrender in return for allowing her husband and her other children to be released and returned to Jerusalem.

Hyrkanos returned to Jerusalem as high priest with reduced authority, as Gabinius divided Judea into five regions, each with its own priest. Antipater’s authority was also reduced, but he continued to govern. Aristoboulos, along with his son Antigonos, returned to Palestine. It is not clear whether Aristoboulos escaped or whether he was released as a result of the bargain his wife had made with Gabinius.

The return of Aristoboulos revived the Jewish resistance. Many Jews responded to Aristoboulos’s call for renewing the war, recognizing that their king had succeeded in escaping from Rome rather than being pardoned by the Senate. A new Jewish army of eight thousand men was recruited, but this force was easily defeated by the well-trained and well-equipped Roman soldiers. Aristoboulos retreated to the fortress of Machaerus with a few men, and after a two-day siege he gave in and returned to Rome. His wife and daughters moved to Ashkelon, which had always been an independent city free of Judean control.

Gabinius was assigned to march to Egypt to suppress an uprising, and a contingent of Jewish soldiers led by Antipater accompanied the Roman legions into Egypt. Antipater cooperated with the Romans in hopes that he would be rewarded. While Gabinius was in Egypt, Alexander recruited more soldiers and started a new campaign targeting Romans in Jerusalem and throughout Judea. The surviving Romans took refuge on Mount Gerizim, where they were besieged. Upon his return from Egypt, Gabinius prepared his army for a decisive battle to crush this new uprising. At the same time, Antipater managed to convince many of the insurgents to go home. In the final battle at Mount Tabor, sixty kilometers north of Shechem, Alexander was defeated and his army was destroyed; more than ten thousand insurgents died in the battle.

Gabinius reorganized the government in Jerusalem, allowing Antipater to play a major rule in Judea’s affairs. In 54 BCE, Licinius Crassus replaced Gabinius as governor of Syria and was assigned by Rome to attack Parthia. In preparation for the war, he went to Jerusalem and appropriated eight thousand talents from the temple to fund the campaign against Parthia, which failed in 53 BCE. Upon his return to Damascus, he faced a new rebellion in Judea led by one of Aristoboulos’ senior officers. In Galilee, he defeated the insurgents, destroyed their army, executed their leader, and had thirty thousand captives sold into slavery.

Thus, during the period between 57 and 54 BCE, there were four uprisings in Judea. John D. Grainger, who has studied the historical records of this period— especially those narrated by Josephus—is critical of these records. He presents a scholarly analysis and conclusions in his book The Wars of the Maccabees:

Uniting [these uprisings] was the fact that they were all attempts to overthrow the settlement imposed by Pompey, and their increasing anti-Roman sentiment. The ferocity of the fighting steadily increased, each Jewish defeat leading to great casualties and to a greater effort. . . .The repeated Jewish risings also developed a pattern by which any Roman setback or distraction—Egypt, Parthia, a defeat anywhere— would be seized on as a signal to attempt a new rising The purpose of the risings had been not just to rid Judea of the Romans, but it had been aimed at restoring full Judean independence. 77

The Roman civil war between Caesar and Pompey began in 49 BCE. During this conflict, Alexander’s family moved from Ashkelon to Iturea under the protection of Ptolemy, the son of Mennaeus. Hyrkanos and Antipater were rewarded by Caesar; Joppa and the Great Plain of Esdraelon were returned to Hyrkanos, and Antipater was given the title of procurator of Judea. Antipater then appointed his son Phasael to govern Jerusalem, and Herod, his other son, to govern Galilee.

In 42 BCE, Mark Antony was put in charge of the eastern Roman provinces. While he was in Rome, the Parthian army invaded north Syria. Ptolemy was succeeded by his son Lysanias, who allied himself with the Parthians. Antigonos, who had been living in Iturea at Ptolemy’s court since 49 BCE, also allied himself with the Parthians. The Parthian army marched south along two routes: the coast road and the interior route. They were welcomed in the Carmel area and Ptolemais. A detachment was sent to Judea. A great uprising in favor of Antigonos erupted in Jerusalem. Herod, Phasael, and Hyrkanos resisted the uprising and fought Antigonos’ followers. The fighting caused many casualties on both sides, and control of the city passed back and forth between the two fighting groups. Hyrkanos and Phasael were captured by the Parthians. Herod managed to escape with the remainder of his forces and was able to reach the fortress of Masada. He left his family in Masada and fled to Nabataea. The Parthians plundered Jerusalem and advanced south toward Idumaea. Hyrkanos was mutilated and sent off in exile to Babylon. Phasael killed himself to avoid being tortured. Antigonos was installed as king and high priest.

Herod left Nabataea and went to Egypt and then to Rhodes, where he communicated with Antony in Rome. Antony, who needed local support in Syria against the Parthians, obtained a decree from the Senate appointing Herod as king of the Jews to bring him to an equal status to Antigonos, who had been appointed as king by the Parthians.

The Romans drove out the Parthians from north Syria; however, they were unable to take Jerusalem, which was controlled by Antigonos. They avoided subjecting the city to a siege, but kept a force in Judea. Herod had landed at Ptolemais, which had returned to Roman control in 49 BCE. He started recruiting to build an army, a mixture of Jews and mercenaries. Then he started a military campaign to capture Galilee. His next target was Joppa. His strategy was to isolate Jerusalem before attempting to assault the city. Over time he gained control of Samaria and Idumaea. Antigonos resorted to guerrilla attacks and ambushes to keep Herod away from Jerusalem.

In the spring of 37 BCE, the siege of Jerusalem started. The city was fortified, since Caesar had allowed Hyrkanos to rebuild the walls. Herod’s forces and the Roman army forces together numbered between thirty thousand and fifty thousand men. It took a long time to isolate Jerusalem from the countryside by building a wall and digging a ditch around the city. As soon as this work was completed, the city was attacked and the walls were breached. As the attackers reached the temple, the defenders were massacred. Herod managed to prevent any looting of the temple. Antigonos was captured and handed over to Antony, who executed him.

Herod had married Mariamme, Alexander’s daughter, just before the siege began. Aristoboulos, a younger brother of Mariamme, was appointed as high priest. The daughter of Antigonos was later married to Herod’s son Antipater. Thus, the Hasmonean family was integrated into Herod’s family in order to forestall any claim to the kingship.

Palestine under Roman Rule

The year 37 BCE marked the beginning of the Roman rule over Palestine. It was the beginning of the reign of Herod the Great as king over a large part of Palestine, including Judea, Idumaea, Perea, and Galilee. During his reign as a client king, people in Herod’s kingdom did not have to pay taxes directly to Rome. Herod’s administration, rather than the Roman tax collectors, was responsible for collecting taxes from the kingdom’s inhabitants. The Palestinians under his rule were spared the humiliations of the Roman soldiers, as the Roman armies were not allowed to enter the country to demand tribute and sell off defaulters into slavery. Herod was responsible for the protection of the empire’s borders against any attack, and for keeping his kingdom in good order and loyal to Rome. He devoted great effort to keeping the kingdom an integral part of the Roman Empire by suppressing any tendency toward resistance in Judea’s population. As a Jew, he encouraged nonpolitical manifestations of the Jewish traditions, such as the legal studies of the Pharisees, but suppressed any manifestations of Palestinian nationalism. He worked to make Jerusalem a Roman city by introducing “the Actian Games” in the Greco-Roman style, with chariot races, theatrical performances, athletic events, and gladiatorial contests. Several buildings were constructed in the city, including an impressive palace for himself.

During Herod’s reign, Jerusalem became a distinguished Roman city, home to about 120,000 inhabitants. Pilgrims visited the city in massive numbers—between 300,000 and 500,000 every year, especially during major religious holidays. 78

Jerusalem’s temple played a major and essential role in the Jewish life not just in Judea, but in the lives of Jews throughout the world. As one of the most important structures in Jerusalem, it drew Herod’s attention. He provided the necessary funds to rebuild it and expand its platform. It included a spacious plaza where merchants and money-changers conducted their business. The money-changers’ mission was to exchange foreign currency for shekels, which were the official currency of the temple. The money-changers were also in charge of collecting the temple tax. Pilgrims would use their new currency to buy offerings that they then passed to the priests who usually were roaming in the plaza.

When Herod died in 4 BCE, the Pharisees, who adhered to the strictest interpretation of the Bible, led an uprising in Jerusalem. Herod’s older son Arcelaus promptly sent the troops into the temple’s courts and brutally crushed the rebels, killing three thousand people. Arcelaus was then summoned with his brothers to Rome to meet Emperor Augustus. While they were away, Varus, the governor of Damascus, sent Roman troops to Jerusalem to crush any protests. The soldiers robbed Herod’s palace and plundered the temple, carrying off a large amount of money.

Augustus split the kingdom among Herod’s three sons: Arcelaus was appointed governor over Judea, Samaria, and Idumaea; Herod Antipas became the governor of Galilee and Perea; and Philip was given Gaulanitis (modern-day Golan). Arcelaus was not given the title of king; he was put on probation, and after ten years he was removed from his post. With this, Palestine was no longer an autonomous princedom; it became a Roman province administered by the Roman governor of Damascus.

Around the time of Herod’s death, a serious uprising erupted in Galilee, led by a magnetic revolutionary preacher known as Judas the Galilean. He was the son of Hezekiah, who had led a revolt in 48 BCE and had been captured and beheaded by Herod. Judas the Galilean founded a new movement: the “Zealot party.” The historian Josephus called this the “fourth philosophy” (to differentiate it from the other three “philosophies”; i.e., the Pharisees, the Sadducees, and the Essenes). “Zeal implied a strict adherence to the Torah and the Law, a refusal to serve any foreign master—to serve any human master at all—and an uncompromising devotion to the sovereignty of God.” 79 Such ideas had existed among the population of Palestine long before Judas the Galilean, but Judas was the first revolutionary to fuse the ideology of zealotry and armed resistance into a single revolutionary force, making resistance to foreign rule a religious duty.

In the time after Herod’s death, Judas and his small army of zealots raided the city of Sepphoris, the capital of Galilee, stole weapons from the armory, and launched a guerrilla war throughout Galilee against the Romans and the wealthy Jewish aristocrats who were collaborating with Rome. Their movement had many sympathizers in Sepphoris and in Galilee. Varus, the governor of Damascus, crushed the rebellion and burned Sepphoris down. 80 But Judas escaped and continued to organize resistance for several years. The Zealot movement grew in size and ferocity throughout the following decade.

In 6 CE, when Judea became a Roman province after Arcelaus was banished, Quirinius, the prefect of Syria, and Coponius, the new procurator, conducted a census to register people and their properties to secure more taxes. Several taxes were imposed: land tax, income tax, a poll tax, a water tax, city taxes, taxes on meat and salt, a road tax, boundary taxes, a market tax, and customs duties. Jews also had to pay taxes for the maintenance of the temple; these were collected by the tax collectors. This oppression encouraged recruitment by the rebels.

After the census was completed, the procurator put in place the infamous system of tax farming, in which tax collection was handed over to private contractors. Those who failed to pay were sold into slavery. Tax collection was not the only hardship inflicted on the Palestinians; they also suffered from the practices of predatory businessmen who came from Rome to enhance their wealth by advancing loans to those who were unable to pay their taxes, charging them up to 50 percent interest and selling them into slavery when they failed to pay. The same unscrupulous characters were also cornering the wheat market and then selling it in areas of shortage at inflated prices. In order to enforce these rules, Roman troops were stationed in several locations in the country ready to inflict all forms of punishment on the farmers. 81

The atrocities and savage practices of the Romans did not stop at the economic measures mentioned above, but extended to other aspects of their life, especially religious practices. The Romans exercised a policy of complete control over the Jewish religious establishment. When Pompey captured Jerusalem, the Roman soldiers entered the part of the temple where only priests were allowed. Then Pompey himself entered the Holy of Holies, that most sacred place, where only the high priest could go once a year on the Day of Atonement. In 39 CE, Emperor Caligula issued a decree ordering that a statue of himself be set up in the temple and worshipped as a god. The high priest became a Roman employee appointed and controlled by the Roman procurator. Even the vestments of the high priest, which were used in the New Year and the Day of Atonement, were kept in the hands of the Romans, to be made available to the high priest only for the day of the ceremonies.

The Palestinian Resistance

The Romans subjected the Palestinian population to the most brutal kind of occupation. They imposed a costly tax system on the peasantry, depriving them from enjoying the fruits of their hard work and driving them to the worst state of poverty. Palestinians generally became landless, and often went underwater in debt and ended up in the slave market. The Romans interfered in all aspect of Palestinian life, including culture, traditions, and religion.

The Arrival of Pontius Pilate

The monotheistic religion of Judaism replaced polytheism in Palestine around the fifth century BCE and became the religion of the majority of Palestinians in the first century BCE. The Hasmoneans had transformed Judaism from a cult religion into a universal one that dominated all aspects of life in Palestine and beyond. During their rule they encouraged proselytization in the neighboring countries around the Mediterranean. Judaism became prevalent in Egypt, North Africa, and Spain. The Jewish community in Alexandria numbered about 500,000, and there were many Jews in the Carthaginian empire. In Babylonia there was a large and prosperous Jewish community that played a major role in spreading Judaism in the neighboring countries, especially Persia. As mentioned above, during Herod’s reign over Judea, large numbers of pilgrims visited Jerusalem every year.

Palestine witnessed multiple uprisings and revolts against the savage oppression of the Roman occupation. The Zealot uprising in Galilee under the leadership of Judas the Galilean between 4 BCE and 6 CE was not the only resistance activity against the Romans; Palestine witnessed many revolts during the first two centuries of Roman rule. Most of the time, the rebel leader claimed to be the Messiah.

Between 6 CE and 26 CE, four governors ruled Judea. In the year 26 CE, Pontius Pilate arrived in Jerusalem as the fifth governor. Pilate was one of the longest-serving governors in Judea; he stayed in his office until 36 CE. Philo of Alexandria, the great Jewish philosopher, summarized his character: “He was cruel and hard-hearted . . . During his reign, men were often sent to death untried.” 82

The main functions of a Roman governor were to ensure an uninterrupted flow of tax revenues to Rome and to maintain a functional relationship with the high priest. Gratus, the governor who preceded Pilate, had appointed five different priests in his time. Pilate had only one high priest to deal with: Joseph Caiaphas. Caiaphas had a close relationship with Pilate, which allowed him to stay in office for eighteen years.

Antonia Fortress, The Temple, Upper City and Lower City, Record Building, Ananias’ House. The map highlights Jerusalem’s defensive structures and central buildings during this tumultuous period.

The Revolt of 67–70 CE

When Pilate was dismissed by Emperor Tiberius in 36 CE, Palestine was assigned, temporarily, to the oversight of the governor of Syria. Caligula, who succeeded Tiberius as emperor, appointed Agrippa I, the grandson of Herod the Great, to rule Palestine. Agrippa I had been raised in Rome in the imperial family. This new king respected the Jewish customs and was able to balance between protecting Rome’s interests and the Jews’ religious autonomy, as his grandfather had.

Agrippa I died in 44 CE; his son Julius Marcus Agrippa (Agrippa II), was seventeen at that time. Claudius, the Roman emperor who succeeded Caligula, felt that Agrippa II was not well prepared to assume the mantle of leadership, so he kept him in Rome. When Agrippa’s uncle, Herod of Chalcis, died in 48 CE, his small kingdom halfway between Beyrut and Damascus was assigned to the young Agrippa. This appointment carried with it the important right of superintending the temple in Jerusalem and appointing the high priest.

The governors appointed by Rome were responsible for appointing procurators, whose role was to maintain law and order in the country and collect taxes. As procurators were unsure of how long their tenure would last, they worked hard to plunder and collect more wealth. Rome tolerated their corruption as long as it did not provoke rebellion.

As mentioned earlier, the first century of Roman rule over Palestine witnessed several uprisings against the repressive policies and practices of the Romans. “As injustices multiplied, so did protests, at first nonviolent, then violent. As protests grew stronger, so did repression. As repression reached its peak under the procurator Gessius Florus in 64–66 CE, the population finally resorted to total renunciation of Roman rule and violent revolt.” 83

Although Agrippa II and the Judean nobles tried to calm the situation in Jerusalem, promising to take matters to the emperor in Rome, the angry masses were inclined to escalate their protest into a full-blown revolution. King Agrippa abandoned Jerusalem and moved back to Caesarea, and the extremists took over forthwith. A group of lower-class priests seized control of the temple, joined by Zealot groups, especially members of the Sicarii. 84 They set fire to the public archives, which included the ledgers of the debt collectors and money lenders, property deeds, and public records, and won the Antonia Fortress, burning it down and slaughtering the garrison. 85 Meanwhile, a group of Sicarii attacked and captured the Masada fortress located at the southwestern corner of the Dead Sea which held arms for ten thousand men and vast stores of food and other supplies. They returned to Jerusalem with their plunder, but Zealot leader Eleazar ben Simon, sensing a threat, captured their leaders and sent them back to Masada.

Meanwhile, the Greeks in Caesarea slaughtered their city’s Jewish community, presumably with Florus’s encouragement. Twenty thousand men, women, and children were killed within an hour. The Greeks massacred Jews throughout Palestine and Syria. In Ashkelon, 2,500 Jews were killed, and as many at Ptolemais (Akka). Thousands more were murdered at Tyre, Hippos, Gadara, and in the surrounding villages. Florus’s calculated refusal to restrain the Caesarean Greeks from launching a pogrom triggered a bloodbath. The Jews attacked Greek towns and villages in revenge, killing large numbers of their inhabitants. The Jewish rebels were also able to capture several fortresses, including Cypros near Jericho and Machaerus on the cliffs east of the Dead Sea. 86

Unable to control the situation, Florus requested assistance from Cestius Gallus, the legate of Syria. Cestius assembled a large force composed of 32,000 soldiers from Antioch and other regions. They landed at Ptolemais on the coast near present day Haifa, marched into Galilee, and commenced a deliberate campaign of terror. Many people were slaughtered, and their homes were looted and burned. The Roman forces managed to control Galilee and the coastal cities within a relatively short period with minimal losses, but suffered considerable losses of troops, equipment, and supplies as they moved inland. Cestius’ assault on Jerusalem ended in a rout at Beth-Horon, with huge losses of men and cavalry. The rebels captured the siege weaponry and heavy artillery, including stone-throwing catapults and large quick-firing mechanical bows. They also captured the eagle standard of the Twelfth Legion. The remnants of Cestius’s forces withdrew back into Syria. 87 With his retreat, many of the most eminent Jews left Jerusalem and fled to Antioch, as they believed that the country would face a new destructive war. Others took refuge in Agrippa II’s territory.

The Rebel Government in Jerusalem

The great victory of the rebels over the Roman expedition at Beth-Horon was seen by the Palestinian population as a divine victory that brought back the memory of the Maccabees’ victory against the Seleucids at the same site. The rebel commanders envisioned themselves as the spiritual heirs of Judah Maccabee. The oppressed masses who started the revolt were extremely encouraged. However, the top-level members of the priestly bureaucracy were the primary beneficiaries, as they formed a war council to prepare for the next confrontation with the Romans. Although they have since been discredited as Roman collaborators, they were accepted as the leaders of the new state. High priest Ananus and the Sanhedrin (a legislative assembly of elders) maintained considerable influence in the new governing authority, and were able to prevent Eleazar ben Simon, who had played an important part in defeating Cestius, from becoming the overall leader. Ordinary people in Jerusalem did not realize that the rich aristocrats who took charge of the city were planning, by taking over the country, to negotiate a compromise peace with the Romans, as they had much to lose if the Zealots were ultimately to take control. The new government divided the country into five regions and selected ten generals to manage these regions. Most of the generals were of aristocratic origin, most notably Ananus and Joseph ben Gorion, who became joint governors of Jerusalem. Coins were minted: silver shekels and smaller denominations in bronze. 88

There had been a significant strain in the relationship between Jerusalem’s Christian church and the Jewish establishment since James the Pillar had been executed in 62 CE (see page XX). Ananus, who sentenced James to death, was now fully in charge of Jerusalem. The Christian community of Jerusalem, under the leadership of Simeon, Jesus’s cousin, decided to leave the city. Their departure meant the severance of any relationships with the Jewish community and the temple.

When Nero learned of his forces’ defeat, he became very concerned that Rome’s enemies, the Armenians and the Parthians, might exploit it. He wasted no time in preparing a massive force to crush the revolt. He appointed an experienced commander, Flavius Vespasian, to lead the new expedition. From 67 to 68 CE, Vespasian crushed the rebellions and systematically moved from one region of Palestine to another, burning and looting in a most vicious manner. Finally, he returned to Caesarea, where he gathered his forces in preparation for the final stage of the war: capturing Jerusalem. When news of Nero’s death on June 9, 68 CE arrived, he decided to suspend military operations and await further developments.

The Year of the Four Emperors

In June 68 CE, the Roman army in Rome and other parts of the empire revolted against Nero. The Senate proclaimed him an outlaw, which meant that he would be executed “in the ancient fashion” (i.e., flogged to death). On June 9, 68 CE, Nero committed suicide. Galba, who was the provincial governor of Upper Germany, was then elected as the new emperor by the Senate. Galba’s only asset was his noble lineage; he was known to be an impotent governor. As a new emperor he was not an effective or popular administrator; he made poor choices when he picked advisers and made bad decisions when he tried to solve the empire’s financial affairs. Such actions caused him to lose the support of the Senate and prompted him to appoint a successor. He chose Piso, an unqualified candidate, to succeed him. Otho, a prominent member of his staff who had expected to be the successor, arranged for the assassination of both Galba and Piso on January 15, 69 CE.

After the assassinations of Galba and Piso, Aulus Vitellius, the provincial governor of Upper and Lower Germany, was declared to be the new emperor by his troops. His army advanced toward Italy and defeated Otho’s army at Bedriacum, near Cremona. At the end of May, Vitellius, at the head of his victorious army, reached Cremona. His troops, who were made up of various ethnic German groups, treated Italy as if it were a conquered foreign land.

As soon as Vitellius had settled in Rome, he sent his representatives to the provincial governors to secure their allegiance. Tiberius Alexander, governor of Egypt, and Mucinius, governor of Antioch, withheld their support; both were in favor of having Vespasian as the new emperor. With their support, Vespasian would have fourteen legions—almost half the entire Roman army. Vespasian’s supporters formed a council of war and established a plan wherein Mucinius would march with his army against Vitellius in Italy, while Titus would assume command of all Roman and allied troops in Palestine and continue the war, and Vespasian would establish himself in Egypt, which was the main grain supplier of Rome. Interestingly, the king of Parthia proclaimed that he “would not only refrain from exploiting the situation to his own advantage, but would commit forty thousand of his mounted archers to assist Vespasian.” While Mucinius’s army was on its way toward Rome, the seven legions of the Danube destroyed Vitellius’s troops at Cremona and advanced toward Rome. In December of 69 CE, Vespasian was declared the new emperor. His army, under the command of Mucinius, arrived in Rome on December 20, 69 CE. He took control of the capital in Vespasian’s name, arrested Vitellius, and executed him. Thus, Vespasian became Rome’s fourth emperor within a single year. 89

The Battle for Jerusalem

As mentioned above, following the defeat of Cestius and his retreat to Syria, a new governing body controlled by the rich aristocrats who always cooperated with the Romans had been established in Jerusalem. Ananus ben Ananus, the former high priest, was in charge of the new system. Most of the Zealots who started the rebellion were peasants whose fight for the freedom of their country was inspired by their religious belief. They were proud of their zeal for religion; this was why they were called the Zealots. They were excluded from the decision-making process by the elites. Eleazar ben Simon, the Zealot leader who had played a major role in the Beth-Horon battle against Cestius, was marginalized and contained by Ananus. However, he managed to retain complete control over the temple. Eventually the Zealots under his leadership were able to depose all the aristocrats from their traditional positions in the temple, including the position of the high priest, and a new high priest from the peasant class was appointed. Then John of Gischala came from Galilee, where he and his supporters had opposed the Roman-aligned governor Josephus and fled from an attack on the city by Vespasian’s son Titus. When John of Gischala entered Jerusalem, he joined the Zealots and provided them with what they lacked: a clear vision and strategy. John was the one who helped develop a plan to take over Jerusalem. He started a real war against the old establishment and led the Zealot revolution.

In response, Ananus ben Ananus organized the elites’ camp and started preparing for a war against the Zealots. He was able to form an army of six thousand fighters. He held public meetings in Jerusalem where he attacked the actions and policies of John of Gischala and his supporters, urging people to confront the Zealots and put an end to their control over the temple. He accused them of being a great threat to the safety of the city.

John of Gischala convinced the Zealots who controlled the temple that Ananus had persuaded his party to send an embassy to Vespasian inviting him to come and take possession of Jerusalem. Then he contacted the Idumaeans and persuaded them to march into Jerusalem and participate in the fight against the moderates who were planning to surrender the city to the Romans. More than twenty thousand Idumaeans joined the Zealots and launched an attack on the moderates gathering in the area around the temple, killing more than 8,500 of Ananus’s supporters. The Idumaeans then rampaged through the city, looting houses and killing everybody they saw. Ananus was hunted down and killed.

It was clearly a class war that ended in favor of the Zealots. John of Gischala became the new ruler of Jerusalem. However, Eleazar ben Simon was unwilling to take orders from him, so the Zealots in Jerusalem split into two hostile factions, with Eleazar’s faction controlling the inner courtyard of the temple while John’s faction controlled the outer one. John of Gischala had the upper hand, and dominated the scene unchallenged from 68 CE until the spring of 69 CE. 90

A new Zealot faction under the leadership of Simon bar Giora evolved in the later part of 68 CE. Simon was born at Gerasa (now Jarash), on the east side of the Jordan River; his father was a Greek who had converted to Judaism. Simon was a Zealot who believed that the upper-class Jewish establishment had betrayed the nation and were collaborating with the Romans.

Simon had played a major role in the Beth-Horon battle against the Roman forces, and Ananus, who controlled Jerusalem after the withdrawal of Cestius, had expelled him from the city. After leaving Jerusalem, Simon had joined the Sicarii in Masada and participated in their raiding campaigns against nearby villages and communities. When Ananus was killed, Simon left Masada and went up into the hill country recruiting fighters and forming an army. As soon as he had gathered a sizable force, he expanded his activities south toward Idumaea. Simon bar Gioras took advantage of the suspension of the Romans’ war campaign and expanded his territory in the south. He fortified the village of Nain and made it his headquarters, and stored food, supplies and equipment in nearby caves. He captured the fortress of Herodium and then mounted a surprise attack against Hebron, looting the city.

The Zealots of Jerusalem became alarmed and concerned about Simon’s intentions. Their fighters ambushed Simon’s troops and captured his wife, expecting him to surrender. On the contrary, however, it made him more vicious and daring. He marched toward Jerusalem, killing the people that he found, though he sent some back to the city alive after he cut off their hands, threatening to storm Jerusalem. The terrified Zealots then released his wife.

Life in Jerusalem under the rule of John of Gischala and his troops became unpleasant and even intolerable. Dissent erupted within John’s own camp and among other segments of Jerusalem’s population, especially among the Idumaeans. The decedents consulted with the remaining chief priests in the temple, who advised them to invite Simon bar Giora to enter Jerusalem, get rid of John of Gischala, and take over the city.

When Simon bar Giora received this request from Jerusalem in the spring of 69 CE, Vespasian had renewed his military campaign in response to Simon’s gains in the south. He sent Roman forces through Samaria toward Jerusalem, taking complete control of Gophna and Acrabata, Simon’s original power base. He also dispatched Cerialis, who led the Fifth Legion from Emmaus to clear the rebels from Idumaea, destroying Bethel and Ephraim, and then moved into Hebron. At this point Vespasian controlled all of Palestine except for Jerusalem, Herodium, Masada, and the fortress of Machaerus.

Simon and his forces were stationed outside Jerusalem’s wall; he accepted the invitation and entered the city, welcomed by the crowds. John of Gischala retreated to the outer court of the temple. Eleazar ben Simon and his faction continued to occupy the inner court, while Simon bar Giora controlled the rest of the city.

Titus Takes Jerusalem

Vespasian remained in Alexandria for much of 70 CE. Titus, Vespasian’s son, was sent to Palestine to finish the mission of crushing the rebels and capturing Jerusalem. Vespasian appointed Tiberius, the governor of Egypt, as Titus’s second in command. (Tiberius, who came from a prominent Greek-speaking Jewish family in Egypt, had denounced Judaism and become an apostate at an early age.) From Alexandria, Titus marched into Palestine through the desert, arriving at Gaza and continuing along the coastal plains toward Caesarea, with the Fifth, Tenth, Fifteenth, and Twelfth Legions under his command. In addition, he had the Syrian auxiliaries and substantial detachments provided by the regional client rulers. In all, the Roman army numbered between fifty thousand and sixty thousand men.

Josephus estimates Jerusalem’s population at the time of the siege at 600,000. The Zealots’ forces were estimated to comprise around twenty thousand well-armed troops. However, the three Zealot factions failed to unite and establish a single defense strategy. On the contrary, they were engaged in internal fights among themselves, as each of the leaders was hoping to establish a new monarchy with himself as king.

Jerusalem was the biggest and the most heavily fortified city that the Romans ever besieged. It is built on high ground (the Four Hills) bordered by deep ravines. On the east and south sides, the Kedron Valley separates the city from the Mount of Olives. On the west side, the Hinnom Valley separates the city from Mount Scopus. The Old Wall encircles the upper city in the north and the lower city in the southeast. The temple, which was located to the northeast, was enclosed by walls that were thicker and more elaborate than any other structure. The fortress of the Antonia, located north of the temple, was a highly fortified structure; it was Jerusalem’s main fortress, dominating the temple and housing the city’s garrison. Herod’s Citadel, located on the northwest side since the Hasmonean times, was built on a fortified hill. Herod had built three towers: Hippicus, Phaseal, and Mariamne. The Hippicus Tower, looking over the Hinnom Valley and facing Mount Scopus, was thirteen meters wide at its base and forty meters high. The Phaseal Tower was twenty meters wide and twenty meters high. Herod’s palace was located south of the citadel.

A second wall had been constructed during Herod’s reign to include a new neighborhood that had sprung up adjacent to the Antonia Fortress, extending from the walls of the Antonia Fortress to the walls of Herod’s complex. The city grew further, extending north of the temple and adding the north high ground, which became known as the fourth hill. King Agrippa I, who governed Judea between 41 and 44 CE, intended to construct a wall to include the expansion of the city. He built the foundations, but was stopped by the Roman emperor Claudius. After Cestius’s defeat, the new authority of Jerusalem completed the wall to enhance the city’s defenses. Nine towers were erected on what became known as the Third Wall, or Agrippa’s Wall.

Titus marched from Caesarea through Samaria to Gophna, and after a long day’s march he camped in the “Valley of Thorns” about five and a half kilometers from Jerusalem. As the Romans worked to establish base camps on the perimeter of the city at Mount Scopus and the Mount of Olives, the rebels sent out sorties to harass them. In response, Titus leveled the ground from Mount Scopus to the wall in front of Herod’s palace and moved his troops to strongly fortified positions out of range of bowmen. From this point on, the defenders did not dare to make sorties outside the walls.

As mentioned earlier, Eleazar ben Simon controlled the inner court of the temple, while John of Gischala controlled the outer courts. Eleazar’s group was well armed and had plenty of food. They occupied the high ground and were able to shoot down on John’s supporters. A constant exchange of missiles between both sides dominated the scene. Simon bar Giora controlled the upper city and most of the lower city. John was attacked continually by Eleazar from above, and by Simon from below. During the skirmishes, John’s men set fire to Simon’s storehouses, and in return Simon’s men retaliated by setting fire to John’s supplies.