An overview of religion in Palestine during the Bronze and Iron ages, followed by a summary of the Mesopotamian religions and Zoroastrianism. An account of the emergence of Judaism and early Jewish history, and examination of the historicity of Old Testament accounts.

Religion in Palestine during the Bronze and Iron Ages

During the Bronze and Iron ages, people in Palestine and the rest of the Near East believed in the concept of the “Divine Council” or the “assembly of gods.” The divine was understood to be the power that controlled and governed the functions of natural and human orders. There is no archaeological evidence to support the concept of monotheism in Palestine during this period; however, people did believe in the concept of a God of gods. As early as the Bronze Age they referred to El as the father of the gods and the creator of heaven and earth, and referred to Asherah or Astarte as the “queen of heaven” or the “mother of all living.” Baal was El’s chief executive. Each major region of Palestine had its own main god apart from El: Baal in Phoenicia, Yahweh in the central highlands, Baal and Yahweh in the southern highlands, Qaus and Yahweh in Edom, and Moloch and Chemosh in Moab. The religious beliefs in the highland states of Palestine did not differ from those of other regions of Palestine or Greater Syria. The religion of Israel and Judea was no different from those of Ammon, Moab, or Edom. Also, it was no different from the religious beliefs in Phoenician cities or in Elba, Ugarit, Hama, or Damascus.

Palestinian religious beliefs shared concepts of both polytheistic and monotheistic ideas; that is, they were henotheistic. This was the case in other parts of the ancient world. People understood gods as the power that controlled their life and destiny. The divine nature of gods in human religious thinking implied the recognition of the spiritual dimension of human life. In the ancient world, people believed that law, justice, and human destiny were all in the gods’ hands. The Code of Hammurabi that was published by the royal court in Babylon (1755–1750 BCE) declared that the king, the obedient servant of the god Marduk, had established justice as God had demanded of him. The concept of the power of the king being based on appointment by the divine is seen in all texts from the law of Sumer to the codification of Roman law. It can be seen in Egypt’s texts as well as in the texts of Assyria and Persia. 1

The Influence of the Ugarit Kingdom

A large number of clay tablets written in what is known as the Ugaritic script, consisting of thirty cuneiform signs representing alphabetic characters, were found in Ugarit, in the northern Levant, in 1929. These texts, dating from the fifteenth to fourteenth centuries BCE, dealt with legal, commercial, and administrative affairs. Many of them were related to religion and mythology, which was very helpful in demonstrating the connection between the religious beliefs of Ugarit and those of the rest of Canaan. It is clear from the textual archives that a large number of deities were worshipped in Ugarit and throughout Canaan. The supreme god was El, the father of the gods and ruler of the divine pantheon. Asherah, who was the marine goddess, was the mother of all gods. El’s divine executive was Baal, who represented the royal power and the authority of God. Baal’s spouse was Anat, the goddess of war and of love. A large number of deities were worshipped by the Canaanites: Shemesh, the sun goddess; Yarih, the moon god; Yam, the sea prince; Dagan, the god of grain; and Mot, the ruler of the underworld. 2

The texts of Ugarit made it possible to reconstruct the Canaanite pantheon and provided poems, myths, and legends of the adventures of the gods and goddesses. Such legends and stories represent the literary heritage of Canaan—which Israel, as a sub-polity of Canaan, also shared. Unsurprisingly, many of these myths found their way into biblical writings. 3 One such example is the myth related to Baal and the primeval serpent, Lothan. This myth is almost identical to Isaiah 27:1, which states: “On that day the Lord shall punish with His great strong sword Leviathan the primeval serpent, Leviathan, the tortuous serpent, He will slay the dragon in the sea.”

In the early religions of Palestine, there were four distinct levels, or classes, of gods and goddesses:

- El, the creator of the world, who fathered the other gods with his spouse: El possessed all of the powers that belong to gods. He was the ultimate and the cause of all existence.

- Major administrative deities: These gods were responsible for all the forces in the ancient world: the state, the army, justice, death, fertility, love, the weather, the sea, etc. They were honored through dedications, monuments, and temples.

- Middle management: These were the gods of families and clans, subordinate to the great or “high gods” and related to specific places or smaller regions.

- Impersonal gods: These deities possessed magical forces of good and evil that supported or terrified people. They included demons, the forces of disease, the power of fertility, the guardians who gave power to the evil eye, the shadows of past dead, or the spirit of an ancestor. 4

The Religion and Mythology of Mesopotamia

European scholars (historians, archeologists, and linguists) became interested in exploring archeological sites in Iran and Iraq in the eighteenth century. Their efforts increased significantly in the mid-nineteenth century, encouraged by their governments’ desire to expand their influence in these countries. The greatest of those scholars was Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, an English soldier, diplomat, and linguist. He was the first to crack the cuneiform code. 5 The excavating expeditions carried out by several archeologists and linguists in the second half of the nineteenth century resulted in the discovery of more than thirty thousand tablets inscribed in the Sumerian language. Publication of some of this material began as early as 1893. 6 George Smith, an apprentice to Rawlinson in t he British Museum in London, was eager to study and translate tablets and fragments that he had labeled as mythological and mythical. In 1872, Smith discovered in one of the tablets an independent version of the flood story, including the wooden ark, that coincided with the biblical narrative right down to the selection of survivors of the flood through the intervention of a god. He concluded that most likely the Bible scribes had borrowed a narrative they had heard when they were held in captivity in Babylon. Smith presented his findings before a large, distinguished audience assembled in the offices of the Society of Biblical Archeology. Rawlinson, when interviewed, emphasized the great commonality between the flood myth translated by Smith and a version handed down by the Babylonian priest Berossus in the third century BCE. 7

The flood story was part of the epic of Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh, the fifth king of the first dynasty of Uruk, is believed to have lived in the period from 2850 to 2700 BCE. After losing his friend and comrade Enkidu to death, Gilgamesh leaves Uruk on a mission to find a man called Utanapishtim, who was granted everlasting life by the gods after the Great Deluge. Gilgamesh’s goal is to find out the secret of immortality, as he has become terrified of death. When Gilgamesh finds him, Utanapishtim relates a tale that bears marked similarities to the biblical story of the flood: Being told by a god that a flood is planned to destroy mankind, he built a boat and took on board “the seed of every living creature.” A storm raged for seven nights and days; when it calmed, he sent out a dove to see if the floodwaters had subsided, but it returned, unable to find food. He tried again with a swallow, and finally a raven, which did not return. Then he and his wife disembarked and made a sacrifice to the gods, who endowed them with immortality. 8

George Smith was involved in the excavation expeditions at the site of Nineveh in northern Iraq for several years, during which he came across nine or ten Assyrian tablets that he named “The Story of the Creation and Fall.” Smith published the narrative of the creation in his book The Chaldean Account of Genesis. The resemblance of this material to the Old Testament chapter of Genesis was unmistakable. In the tablets, the epic of Enuma Elish describes a time when nothing existed aside from the divine parents, Apsu and Tiamat, and their son Mummu. Apsu was the primeval sweet-water ocean, and Tiamat the saltwater ocean, while Mummu represented the mist rising from the bodies of water and hovering over them. These three types of water were mingled in one mass that contained all the elements needed to create the universe. 9 The people of ancient Mesopotamia did not question how the primordial elements came into being.

Heaven was created of its own accord. Earth was created of its own accord. Heaven was an abyss, earth was an abyss.

All Mesopotamian creation stories were based on the existence of heaven and earth. In ancient Mesopotamia, the human race was created from clay, mixed with divine blood. Man was created to take over the gods’ work so the gods could rest. Personal well-being was tied to correct worship of the gods. If an individual sinned or a community neglected the proper rites, disorder, plague, earthquake, fire, or other evils could befall the entire community. 10

During the fourth millennium BCE, early Mesopotamians regarded the supernatural forces that controlled their life as mysterious and impersonal. They believed that storms, rivers, lakes, marshes, mountains, sun, wind, and fire were beings, and so they worshipped all forces of nature. During the third millennium, as Mesopotamia entered the city-state period, these nature gods were transformed into city gods or heads of state. The Sumerian theologians assumed that a pantheon made of a group of living beings—humanlike in form but superhuman and immortal—were operating, directing, and supervising the universe. This pantheon controlled the cosmos in accordance with well-laid plans and laws. They functioned as an assembly with a king at their head; their mission was to protect their realm against external enemies and internal lawlessness. 11

An, the god of the sky, was the supreme ruler of the pantheon. All things on heaven and earth conformed to his will. Enlil, “Lord Wind,” became the leader of the pantheon around 2500 BCE. Enlil is known as “the father of the gods, the king of heaven and earth, the king of all the lands.” The Sumerian myths and hymns portray Enlil as the creator of the cosmos. Enki (called Ea in Akkadian) was the god of wisdom who organized the earth in accordance with the decisions of Enlil. Ninmah was the mother-goddess. She may originally have been Ki (mother-earth), who shared power with An, the sky god. In one of her myths, she plays an important role in the creation of man, and in another she starts a chain of divine births in Dilmun, the paradise of the gods, which leads up to the “forbidden fruit” motif. Sumerians cherished goodness and truth, law and order, justice and freedom, mercy and compassion. The gods empowered rulers to establish law and order, to protect the weak from the strong and the poor from the rich, and to wipe out evil and violence.

Zoroastrianism: The Start of Monotheism

The Persians were the nomadic people known as the Indo-Europeans who migrated to Persia from the region of Central Asia known now as the southern steppes of Russia. Their religion was based on the same principle as all ancient religions: the concept of a pantheon of gods. The Persian pantheon held three principal gods: Varuna, the god of the oath and lord of the waters; Mithra, the god of the covenant and lord of fire; and Ahura Mazda, the lord of wisdom.

Zoroaster (Zarathustra in Persian) was the prophet of the first revealed religion of the world, Zoroastrianism. Many historians believe that Zarathustra had lived between 1400 and 1000 BCE. He was probably born in what was then northwestern Persia, roughly where the boundaries of modern Iran, Afghanistan, and Turkmenistan meet today. 12 At the age of twenty, he left home and began a period of wandering inquiry about the nature of righteousness. From when he was twenty to when he was thirty, he lived in solitude on a mountain, searching for answers. At the age of thirty he met a glorious angel, Vohu Mana, on a riverbank. The angel asked him who he was and what the most important thing in his life was. Zarathustra replied that he wanted most of all to be righteous and pure and to gain wisdom. With that, the angel led him into the presence of Ahura Mazda, who was accompanied by six other angels. It was there and then that the prophet received his revelation. 13

Mary Boyce, a leading scholar of Zoroastrianism at London University, states clearly the role of Zoroastrianism in shaping the teachings of Judaism and other monotheistic religions:

Zoroaster was thus the first to teach the doctrines of an individual judgment, heaven and hell, the future resurrection of the body, the general Last Judgment, and life everlasting for the reunited soul and body. These doctrines were to become familiar articles of faith to much of mankind, through borrowings by Judaism, Christianity, and Islam; yet it is in Zoroastrianism itself that they have their fullest logical coherence, since Zoroaster insisted both on the goodness of the material creation, and hence of the physical body, and on the unwavering impartiality of divine justice. According to him, salvation for the individual depended on the sum of his thoughts, words and deeds, and there could be no intervention, whether compassionate or capricious, by any divine Being to alter this. With such a doctrine, belief in the Day of Judgment had its full awful significance, with each man having to bear the responsibility for the fate of his own soul, as well as sharing in responsibility for the fate of the world. 14

R.C. Zaehner, former chair of Eastern religions at Oxford University, states:

From the moment the Jews first made contact with the Iranians they took over the typical Zoroastrian doctrine of an individual afterlife in which rewards are to be enjoyed and punishment endured. This Zoroastrian hope gained ever surer ground during the interestamentary period, and by the time of Christ it was upheld by the Pharisees, whose very name some scholars have interpreted as meaning “Persian”; that is, the sect most open to Persian influence. 15

The basic principles of Zoroastrianism are as follows:

- Ahura Mazda (Spenta Mainyu, which means holy spirit) is the one eternally existing god and supreme creator of all that is good, including all beneficent divinities.

- Ahriman (Angra Mainyu, which means the hostile spirit) is also equally uncreated and eternal, and represents wickedness and cruelty and all that is bad.

- Free will—Ahura Mazda does not control every aspect of human life. At creation he gave humanity the gift of free will, which gave humans the choice to do the will of Ahura Mazda, to live according to the teachings of Zoroaster: Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds. Upon death, the individual soul is judged according to what it has done in this life. Each soul must depend on its own ethical achievements when judged. If the good are heavier than the bad, then the soul is judged worthy of paradise; otherwise, the soul is led to Hell. 16

The battle between the perfect good and the spirit of evil will continue for several thousand years. At the end of this period, a savior will lead people successfully against the forces of evil and ignorance. When the forces of darkness and evil are annihilated in the last great battle, resurrection will occur, followed by the last judgment, in which all the righteous are separated from the wicked—both those who have lived until that time and those who have been judged already. At this point Ahriman (Angra Mainyu) and all traces of wickedness in the universe will be burned in Hell, and the world will be restored to its original perfect state.

The Emergence of Judaism

The Semites

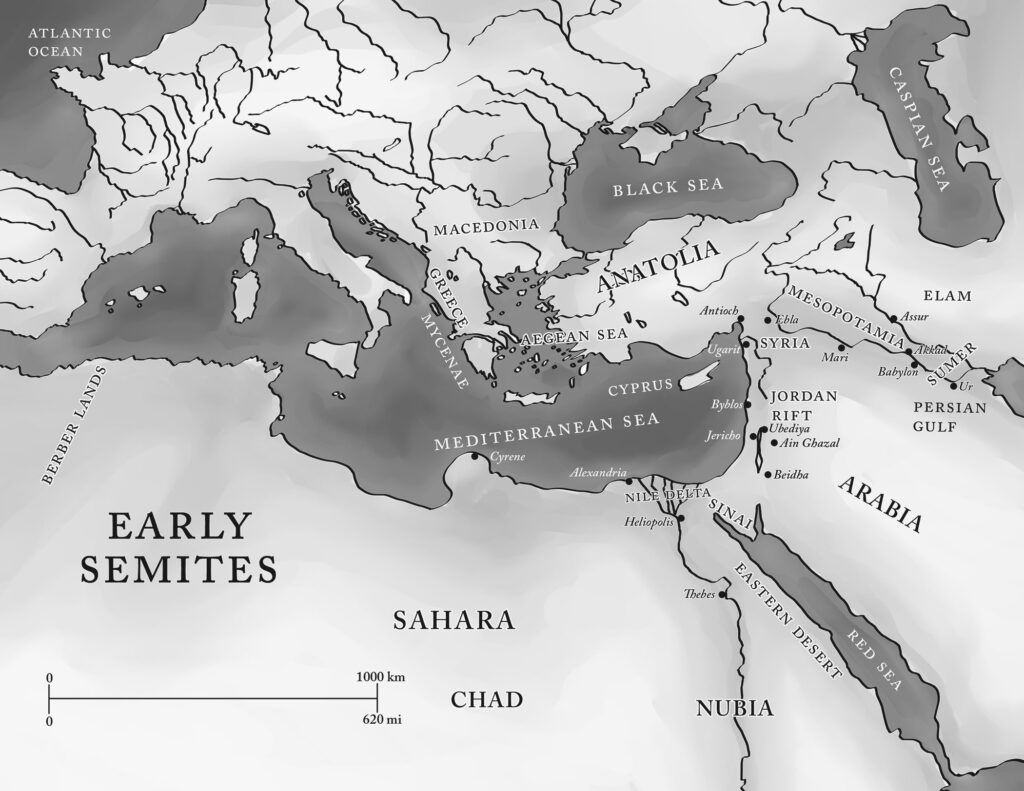

The term “Semite” comes from the mythology of the Old Testament, which states that the Semites are the descendants of Noah’s eldest son Shem. “According to scientific usage . . . the term is a linguistic one; it applies to him who speaks or spoke a Semitic language. The Semitic languages are now recognized as a distinct family comprising Assyro-Babylonian (Akkadian), Canaanite (Phoenician), Aramaic, Hebrew, Arabic and Ethiopic.” 17

During the nineteenth century CE, Western historians introduced the theory that the Semites originated in Arabia, migrating to the Fertile Crescent in the third millennium BCE in search of more fertile land. This theory was not based on any historical records or archeological finds; it arose from the belief of some scholars that the Semitic languages are closer to Arabic than to the old Akkadian and Babylonian texts of ancient Mesopotamia or the texts of Ugarit of Syria. Those scholars believed that around 3500 BCE, a Semitic migration from Arabia moved northeast and settled among the highly civilized Sumerian population of Mesopotamia, producing the Akkadians (later known as the Babylonians). A millennium later, another wave brought the Amorites, who settled in the northern plains of Syria and then moved to Mesopotamia, and the Canaanites, who settled in the plains of Palestine. These historians also invented the story of a third wave of semi-nomads, the Aramaeans, who moved from Arabia into central and northern Syria between 1500 and 1200 BCE, supposedly founding the states of Aram, Ammon, Moab, and Edom in Syria and eastern Palestine. 18

During the 1950s and 1960s, German scholars who had begun to recognize close similarities between verbs in the Akkadian language and in some of the languages of North Africa developed a new theory about the origin of the Semitic languages. This theory held that the Semitic languages that developed among the sedentary agriculturists of Syria-Palestine and then in the Mesopotamian heartland were closely related to a number of African languages: the Berber and Egyptian languages, as well as the Cushite language of the modern Sudan and the language of Chad south of the Sahara.

A third theory emerged in the 1970s, when texts from ancient Elba in Syria were discovered which showed that West Semitic had been the language spoken in all the regions of Syria and Palestine during the third millennium BCE. The West Semitic languages have a common vocabulary for words related to agriculture, horticulture, and sheep- and goat-herding. This vocabulary must have been utilized by people who were both sedentary and agricultural, not Bedouins. As Mesopotamia had a very short period of pre–Bronze Age settlements, Syria and Palestine most likely were the region of the earliest development of the Semitic languages. By the 1980s, the Semito-Hamitic (also known as Afro-Asiatic) theory had gained more support from archeologists and linguistic historians, and became the most prominent theory. 19

The above-described migration-from-Arabia theory collapsed, as it lacked any support from historical texts or archaeological research. Greater Syria (Palestine-Syria) had been inhabited by an advanced population who had established hundreds of villages and towns since the beginning of the Neolithic Age.

The Concept of Monotheism

Judaism as a monotheistic religion evolved during the fifth century BCE. In 586– 587 BCE, many of the citizens of the kingdom of Judea had been exiled to Babylon. Around 550 BCE, the Persian ruler Cyrus II launched a political campaign prior to his military advancement toward Babylon, promising that he would honor the gods, restore the temples, rebuild the ruined cities, and restore a universal peace. He presented himself as the one chosen by the gods to return the scattered people to their homelands and to restore their temples and religions. In 539 BCE, he issued a decree allowing the Palestinian exiles in Babylon to return to Jerusalem and rebuild their temple. A number of groups and their families were transferred from Mesopotamia and resettled in southern Palestine. They established a new colony in and around Jerusalem. 20 The rest—possibly the majority—chose to remain in the cultural centers of the flourishing east. 21

The exiles in Babylon were influenced by the culture and religious concepts of Persia, which were based on universal theology. They were exposed to Zoroastrianism, which was an expression of monotheism. The interaction between the exiles and their descendants on one hand and the center of high culture of Babylon on the other provided the foundation for Judaism as monotheistic religion. The exiles in Babylon were engaged in a remarkable religious reform that evolved into the monotheistic religion of Judaism. 22

During the Persian rule over Palestine (538–332 BCE), the inhabitants of Yehud were referred to as Yehodim. This is a religious description, not a geographic or ethnographic one, meaning the adherents of Yahweh. The term “Jews” was also used as a religious description of those people. “Judaism” refers to religious and philosophical traditions which embrace the classical world of monotheism. This term does not apply only to the Yahweh temple community of Jerusalem, but also includes all the communities associated with other Yahweh temples and cults. It is a theological definition, not an ethnic one. It includes all variant historical forms of the religion throughout Palestine and the shores of the Mediterranean: the Shomronim of Samaria, the Samaritans, the Hellenistic Jews of Philo in Alexandria, the Elephantine colony, the Zadokites and Nazirites, the Essenes, the Saducees, and the Pharisees. 23

The Persian kings adopted a policy of granting their subjects a certain level of autonomy. Palestine was divided into several districts. The southern highlands of Palestine, referred to in the Assyrians’ records as Judea, became known under Persian rule as the province of Yehud, which was limited to Jerusalem and the surrounding countryside. 24 The people of Yehud were managed by a dual system: politically by governors appointed by the Persian authority, and religiously by priests. Yehud was of great strategic value because of its location on the border of Egypt. Palestine remained in the hands of the Persians for two centuries until the conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great of Macedonia in 332 BCE. 25

Under Xerxes (r. 486–465 BCE), the Persians adopted a policy of centralized control over religious ideology by banning pluralist religious ideas. 26 This appears to have been the turning point toward exclusive monotheism in the Near East. This ideology was clearly stated in the Persian and Aramaic texts of Cyrus’s era (590–529 BCE), which expounded on a single god who controls human life—Ahura Mazda in Persia; Marduk in Babylon; Sin in Haran; Baal Shamem in Greater Syria; and Elohe Shamayim, later called Yahweh, in Palestine.

The first group of exiles returned to Palestine under the leadership of Sheshbazzar (a member of the exiles’ royal family) shortly after Cyrus defeated Babylon. A few of them actually stayed in Jerusalem; others settled in the countryside south of Jerusalem. Hardly any building work was done at this stage. The second group came after Darius’s accession, under the leadership of Zerubbabel, who was appointed as the high commissioner of Yehud. He gathered all the returnees in Jerusalem to build a temple. They started with the altar, and when it was finished, they began to offer sacrifices. The building work was stalled due to the deterioration of the economy. Construction resumed in 520 BCE, and was completed in March 515 BCE. From the start, the temple was a disappointment for the returnees, as it was so modest and simple. 27

The returnees to Jerusalem from Babylon were a minority in Yehud. However, they were closely connected with the Persian administration. They were of high social, religious, and economic status, which gave them power far beyond their number. They were able to control the entire population of Yehud because they were in control of the temple. The main goal of these elites was to reunite the community around the new temple. According to Thomas Thompson, the construction of the temple by the returnees in the fifth century was a great historical event that triggered and initiated the process of the formation of the Old Testament. He believes that the process of the Bible formation could possibly have started as early as 450 BCE (the Nehemiah and Ezra periods) or as late as the second century BCE (the Maccabean period). 28 Benedict de Spinoza stated in his Theological-Political Treatise that “the main books of the Bible were written and theologically engineered only after those who left Babylon arrived in Jerusalem, and even at a later time, during the Hellenistic period.” 29 The community of authors was most likely large and diverse, and maintained constant contact with the centers in Babylon. It is obvious that the texts were repeatedly written and rewritten over a period of many generations, resulting in repeated accounts, the absence of narrative consistency, lapses in memory, changes in style, and significant numbers of contradictions. 30

The Old Testament contains a large collection of stories that were circulating among the inhabitants of the entire Near East. The creation stories of the Old Testament are borrowed from the creation mythology of the Sumerians. The flood- and-ark epic was part of the epic of Gilgamesh, as mentioned above.

The returnees who had been born and raised in Babylon considered themselves superior to their neighbors in other parts of Palestine. According to Israel Finkelstein, this separatist ideology was behind the composition of the biblical narrative. The biblical scribes invented the ethnicity myth, claiming that the inhabitants of the central and south highlands were descendants of immigrants from Mesopotamia during the third millennium BCE, and from Egypt during the thirteenth century BCE. 31 Both Mesopotamia and Egypt were considered the most prestigious cultural centers in the Near East. This story was also behind the separatist ideology that dominated the Old Testament: “The Jewish people are the people chosen by God.” It is also behind the violent nature of their religion. The authors of the biblical texts not only opposed the inhabitants of the land, but called for their complete eradication to make room for God’s chosen people. God addressed Moses: “But in the cities of these peoples that the Lord your God is giving you for an inheritance, you shall save alive nothing that breathes” (Deuteronomy 20:16).

The Bible describes the extermination of the local population of Palestine after the conquest of Jericho by Joshua: “They completely destroyed everything in the city with the sword, every man and woman, both young and old, and every ox, sheep, and donkey” (Joshua 6:21). “So Joshua conquered the whole region, the hill country, the Negev, the Judean foothills, and the slopes, with all their kings, leaving no survivors. He completely destroyed every living being, as the lord, the God of Israel, had commanded” (Joshua 10:40). “And all the spoil of these cities and the livestock, the people of Israel took for their plunder. But every person they struck with the edge of the sword until they had destroyed them, and they did not leave any who breathed” (Joshua 11:14).

Judaism started in Jerusalem as an exclusive cult for the returnees (golah), and continued as such for a while. The cult members were prohibited from integrating with the simple rural people of the land, and from marrying into local pagan families. Those who married local women were ordered to divorce them, and those who had returned from Babylon were forced to import wives from Babylonia. These policies were behind the composition of such prohibitions in the Deuteronomy. Moses issued the following instructions:

When the Lord your God brings you to the land that you are entering to take possession of it, and clears away many nations before you, the Hittites, the Girgashites, the Amorites, the Canaanites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites, seven nations more numbered and mightier than you, and when the Lord your God gives them over to you, and you defeat them, then you must devote them to complete destruction. You shall make no covenant with them and show no mercy to them. You shall not intermarry with them, giving your daughters to their sons or taking their daughters for your sons. (Deuteronomy 7:1–3)

The Samaritans

The definition of the Samaritans and Samaritanism contains three principal elements: First, their self-awareness as a religious sect; second, their use of the Samaritan Pentateuch; and third, their preference for Mount Gerizim (the south mountain of Nablus) as the proper place of worship.

The term “Samaritan” refers to a well-defined and self-conscious religious sect that uses a version of the Pentateuch called the Samaritan Pentateuch as its sacred text; they honor Mount Gerizim as the proper place of worship. 32

The Hasmonean period (168–123 BCE) can be identified as the beginning of the Samaritan religious sect. The sect emerged on the historical horizon during the middle of the second century BCE. The Samaritans believe themselves to represent the orthodox faith; they hold that Judaism is the deviant. This understanding is reflected in their self-designation: “Shomrim,” which means “keepers of the Torah.” 33

When Jesus conversed with a Samaritan woman at Sychar, near Shechem (modern-day Nablus) on various subjects, including Jewish-Samaritan relations, the woman was amazed that Jesus was even talking to her, and said: “Jews do not share [things] in common with Samaritans” (John 4:9). Later, the woman told Jesus: “Our ancestors worshiped at this mountain [Gerizim], but you [Jews] say that the place at which God must be worshipped is in Jerusalem” (John 4:20). The conversation between the Samaritan woman and Jesus reflects the strained relations between Samaritans and Jews in the early centuries of the Common Era. Both Samaritans and Jews advocated centralization (as demanded in the Torah [Deuteronomy 12])—the firmly held tenet that the God of Israel had to be worshipped only at one location—but differed strongly about where that worship was to be centered (Mount Gerizim vs. Mount Zion). 34 The Samaritans are the descendants of the inhabitants of the city-state of Israel,

in the central hills of Palestine, founded by its leader (king) Omri in the early ninth century BCE. Its capital was Samaria. This state lost its independence in 733–732 BCE, when the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III invaded Syria-Palestine and defeated the house of Omri. The Assyrian king Shalmaneser V captured Samaria in 722–721 BCE after a two-year siege. The new Assyrian king, Sargon II, who succeeded Shalmaneser in 720 BCE, implemented the Assyrian bidirectional deportation policy. During the reigns of Shalmaneser and Sargon, the deportation of Israel’s inhabitants and the importation of foreign peoples resulted in demographic and religious transformation. The Assyrian royal inscriptions mention the arrival of state-sponsored immigrants in Samaria; however, the numbers of foreign imports did not appear to be high, and it seemed that the immigrants were gradually absorbed into the local population. Archeological findings demonstrated continuity in material culture in the city of Samaria and the Samaritan hill country, which indicates that neither the Assyrians themselves nor the immigrants they sponsored were sufficient in number to replace the Israelites. 35

The Samaritans, who prefer to call themselves Israelites (not Israelis), claim that they originated in the eleventh century BCE. According to the Samaritan book of Joshua (which is different from the biblical book): “Joshua assembled the tribes of Israel at Shechem for the reading of a new covenant.” It was at Shechem (now called Nablus) that the Israelites, under the leadership of Joshua, had affirmed their covenant after occupying the land of Canaan, making Shechem the original holy place of all Israel. The deviations from the pure Israelite religion began with Eli and Samuel, continued with David and Solomon, and were pursued with vigor by Ezra after the Babylonian exile. According to Samaritan tradition, Ezra corrupted the Torah with the addition of “fables, legends, and lies,” insisted on a temple in Jerusalem, and falsely claimed that the Samaritans were of Gentile descent. The Samaritans and the Jews agree that the eventual split between the two groups had at its core a division within the priesthood. The Samaritans claim an uninterrupted succession of priests and worship on Mount Gerizim, preserving the ancient tradition of the “House of Joseph.” 36

The Jewish interpretation of the origins of the Samaritan group is based on 2 Kings (17:25–26), which refers to the devastation of the northern kingdom of Israel in the eighth century BCE. The Bible implies that the Samaritans descended from peoples who had been deported by the Assyrians from other parts of their vast empire. Among those who resettled in Samaria were people from Cuthah, the region surrounding an ancient city of the same name northeast of Babylon. This was one of the lands conquered by the Assyrians and subjected to the policy of forced migration. Eventually “Cuthean” became the Jews’ name for the Samaritans and thus a reminder of Jewish contempt for these genetically and religiously impure persons. The biblical story of 2 Kings 17 emphasizes that these “Cutheans,” deported by the Assyrians, adopted a form of the Israelite religion in part as an effort to ward off a plague of lions sent by God as punishment for ignoring Him. These “lion proselytes” were never to be trusted, and certainly were not honored with the name “Israelite,” because their syncretistic form of worship recognized a multiplicity of deities (2 Kings 17:33). In fact, however, Cutheans were simply the inhabitants of the north; they were not Samaritans. Sargon’s deportation of the indigenous Israelite population from Samaria primarily affected the aristocracy within the city. The groups brought into the region to replace the deportees remained a minority. In the Bible, 2 Kings refers to this select few and not the general population, and certainly not a religious sect that had not yet attained a sense of self-awareness (i.e., the Samaritans). The prophetic books (Isaiah through Malachi) contain indirect evidence that the schism between Jews and Samaritans had not taken place by the fifth century. These prophetic texts do not mention a group called the Samaritans. 37

The Assyrians were not consistent in their administrative polices in Samaria; while they deported some Israelites, they left many others in place, which explains why the region of Samaria made a swifter recovery after the Assyrian campaigns than Judea did after the Babylonian invasions in the sixth century BCE. Under Nebuchadnezzar, the Babylonians took a much more devastating approach to dealing with rebellions in Palestine. Excavations in Jerusalem indicate that the Babylonians did massive damage to the city’s fortifications and major buildings. The contrast with the relatively lenient treatment given to the city of Samaria is striking. The Assyrians were much more interested in directing the resources of their empire toward exploiting the possibilities for trade and commerce in the southern Levant than the Babylonians were. 38

In the mid to late fifth century BCE, Nehemiah, the governor of Persian Jerusalem under Artaxerxes I, not only was trying to build a physical wall, but also was creating an ethnic wall between Judea and Samaria. Such concentrated efforts by Nehemiah were repeatedly met with resistance from high-ranking members of his own elite, who advocated cooperation between the Judeans and the Samaritans. The tensions between Nehemiah, Sanballat (the governor of Samaria), and Tobiah (an Ammonite official) reveal that Yahwists in Judea, Samaria, and other regions were concerned about their own ethnic identities. Nehemiah’s campaign to create a more independent Yehud set an important precedent for later Judean rulers, especially the Maccabees. It is important to mention here that some of the Judeans disagreed with major components of Nehemiah’s national agenda. The fact that Nehemiah felt compelled to justify his harsh treatment of his opponents indicates that there were other viewpoints that held sway within the community. This was also evidenced by the fact that there was no major breach between Samaria and Judea during this period. 39

During the Hellenistic period, both Samaria and Judea faced challenges and suffered from significant political and economic decline. In 331 BCE, Samaritans murdered the Macedonian-appointed prefect of Syria. Alexander’s forces carried out a punitive campaign against the Samaritans. Alexander destroyed the town of Samaria and settled a colony of Macedonians at the site. In 296 BCE, Ptolemy I deported many captives from Jerusalem, Samaria, and Mount Gerizim to Egypt. However, during the same period, certain areas in Palestine witnessed growth and prosperity. The region of southern Samaria increased in population and material wealth, and around 200 BCE, Seleucid ruler Antiochus III accorded the Mount Gerizim temple the same privileges he accorded to the Jerusalem temple. The Samaritans at Mount Gerizim managed to expand the temple complex, and were able to build sections of a city wall on the southern edge of the site, in addition to towers, large domiciles, service buildings, courtyards, oil presses, storage jars, and various lamps. The Samaritan Yahwists during this period expanded to different regions of the Mediterranean. Two Samaritan inscriptions dating to the late third and early second century BCE were discovered on the Aegean island of Delos; in these inscriptions, there is a mention of “the Israelites in Delos who make offerings for the temple of Mount Gerizim.” 40

The early Hellenistic period witnessed periodic cooperation among members of the Yahwistic elites of Samaria and Judea. Many Judeans emigrated northward to Samaria during this period. The Samaritan governor Sanballat persuaded Alexander the Great to assist the Samaritans in constructing their own temple. Now the two Yahwist sects were able to build their own temples, one on Mount Zion and the other on Mount Gerizim. A Judean priest from the elite priestly family of Jerusalem was appointed as the high priest of the temple of Mount Gerizim. The Samaritan and Judean Yahwists worked together to create a common collection of prestigious scriptures: the Pentateuch, or the five books of Moses, the authoritative set of stories and laws revealing God’s will for Israel. It is not clear how such a process of scribal communications was achieved. Not much is known about the interactions between the political and religious leadership of the two provinces, but it is important to recognize the existence of one vital social and religious institution shared by the two: the Aaronide priesthood. The temple priesthoods at Mount Gerizim and Mount Zion both claimed a common priestly pedigree. Each sought to legitimize its sacerdotal leadership by tracing its origin to Moses’s brother Aaron, the authoritative high priest of the Sinaitic period. Each tradition acknowledged that the priests serving at the other group’s temple were also of an Aaronide pedigree. The fact that the Aaronide priesthood controlled both temples undoubtedly facilitated contacts between the two communities. In an age in which both Judea and Samaria were occupied by the same foreign regime and subject to its administrative, military, and economic policies, the Pentateuch provided each group with a larger social and religious identity. 41

The Deuteronomic laws of centralization mandated cultic unity, involving only one sacred site, and cultic purity throughout the entire land (Deuteronomy 12:1– 13:1). Such regulations entailed the elimination of all non-Yahwistic sanctuaries and all rival Yahwistic sanctuaries to the central sanctuary. How did the Samaritans and the Judeans resolve this issue, and accept two sacred sites?

Textual and literary evidence . . . indicates that the Pentateuch shared by the Judeans and the Samarians was ultimately a compromise document, a work that could (and did, and does) function as scripture for both communities The ambiguous phraseology in the centralization legislation in which the site of Yhwh’s own choosing goes unnamed was a critical component of the Judean-Samarian compromise. Such imprecise language could be (and was, and is) interpreted differently by each group. The lack of definition in this critical edict allowed for multiple readings and sustained the notion that both Samarians and Judeans belonged to a larger people called Israel. Both societies were bound by the same authoritative scriptures, even if they understood some key texts in these common writings differently. 42

The mid- to late second century BCE witnessed a decline in the position of Samaria and a rise of the position of Judea. During the Maccabee era (167–37 BCE), Judea gradually came to dominate the southern Levant. The Maccabees (discussed later in this chapter) expanded their state into Samaria, Idumea, Galilee, Gilead, Perea, Moab, and beyond. In 111–110 BCE, the Maccabean high priest John Hyrcanus laid siege to Mount Gerizim and defeated the Samaritans, destroying their sanctuary. His forces also captured Shechem and reduced it to a village. The destruction of the Mount Gerizim temple ended the existence of the chief Yahwistic competitor to the Jerusalem sanctuary within the land and swung the pendulum entirely toward Judea. If Samaria had been the dominant power in relationship to Judea during the Neo-Babylonian and part of the Persian period, the opposite was now true. With a Maccabean leader in charge of Judea—which expanded to include all of Palestine— there was no longer any need to contemplate points of strategic cooperation with Samaria. For John Hyrcanus, exterminating the Mount Gerizim temple not only fulfilled the centralization mandate but also consolidated political, sacerdotal, and economic power in Jerusalem. However, this achievement came at a significant cost. The military and religious victory of Hyrcanus resulted in tremendous Samaritan resentment and prompted their scribes to create a new edition of the Pentateuch that differed from the Jewish Pentateuch in a number of critical respects. By including Mount Gerizim in a revised version of the “ten words,” Samaritan scribes ensured that the recently destroyed central temple was indelibly and perpetually enshrined within the scriptures they held dear. In effect, the Samaritan scribes removed ambiguities and rendered explicit what they thought that the Pentateuch had meant in the first place. The Samaritan additions to the books of Moses distanced these texts from those of their Judean counterparts. What differentiates the Samaritans from the Jews is not just their Samaritan Pentateuch, but also “the delimitation of the canon to the five books of Moses, the belief in the exalted status and uniqueness of Moses as a prophet (and the concomitant rejection of the prophets and the prophetic books in the Jewish Tanakh), the belief in the unity of God (monotheism, transcendence, constancy, eternity, power, justice, and mercy), the practice of their own calendar, and the belief in a day of divine vengeance and recompense.” 43

The Old Testament and Early Jewish History

The Old Testament is a collection of legends, laws, poetry, philosophy, and history. It is the central scripture of Judaism and the first part of Christianity’s canon. It is also an essential reference of the teachings of Islam conveyed through the Quran, which includes the biblical stories of all the Jewish prophets. It consists of thirty-nine books that can be divided into three main sections:

- The Torah (the five books of Moses, or the Pentateuch), which includes Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

- The Prophets, which is divided into two main groups: the former prophets (Joshua, Judges, 1 Samuel, 2 Samuel, 1 Kings, 2 Kings) and the later prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi).

- The Writings, which is a collection of homilies, poems, prayers, proverbs, and psalms.

For a relatively long period of time, Western historians considered the Bible to be a historical account, and used the Old Testament narrative as a reference for the history of the Near East. However, the second half of the twentieth century witnessed major archaeological advancements that led to reevaluation of this position. The historicity of the biblical narrative became the subject of debate for decades. This debate has intensified in recent years, especially since the early 1990s. Archaeology contributed greatly to this debate, as it utilized anthropology and ethnography in studying archaeological finds. However, some biblical archaeologists used archaeology to promote the biblical narrative as a real history in spite of the absence of actual support in archaeological finds. As an example, Nelson Gluek, the archaeologist who was involved in the excavation at Tell el-Kheleifeh at the tip of the Gulf of Aqaba, interpreted the remains in this region as evidence of a huge copper-smelting industry in the days of King Solomon. This romantic image later proved to be a fantasy—a wishful illusion based on the biblical text rather than on actual archaeological evidence.

For centuries, readers of the Bible unquestioningly believed that the scriptures were both divine revelation and accurate history conveyed directly by God to a wide variety of sages, prophets, and priests. The Pentateuch—the five books of Moses, including the book of Deuteronomy—was supposed to have been set down in writing by Moses himself, even though Deuteronomy describes in great detail the precise time and circumstances of Moses’ own death. This raised a troubling question: how could Moses describe his own death?

By the nineteenth century CE, biblical scholars had concluded that the Pentateuch was the product of several writers, noting that the book of Genesis contained two conflicting versions of the creation (1:1–2:3 and 2:4–25), two different genealogies of Adam’s offspring (4:17–26 and 5:1–28), and two flood stories (6:5–9:17). Most scholars now believe that the Bible was composed, compiled, and edited by priests and scribes as late as the Hellenistic period (fourth to second centuries BCE).44 Archaeology played a crucial role in the debate about the composition and reliability of the Bible. By the end of the twentieth century CE, archaeology had shown that the Bible was a fanciful collection of priestly literature, written with no historical basis at all. Israel Finkelstein concludes: “The biblical stories should be regarded as a national mythology with no more historical basis than the Homeric saga of Odysseus’s travels or Virgil’s saga of Aeneas’s founding of Rome.”

A brief summary of Old Testament stories is presented below, followed by a summary of the archaeological finds related to these stories.

The Biblical Patriarchs

According to the Bible, Abraham originally came from Ur in southern Mesopotamia and resettled with his family in Haran, on one of the upper Euphrates tributaries in northern Syria. In Haran, God appeared to him and commanded: “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land I will show you. And I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great so that you will be a blessing” (Genesis 12: 1–2). Abram (as he was then called) obeyed God, took his wife Sarai (as she was then called) and his nephew Lot, and departed for Palestine. He wandered with his flocks throughout the central hill country between Shechem, Bethel, and Hebron. During his travels, he built altars to God in several places.

God promised Abram and his descendants all the lands from “the River of Egypt to the great river, the River Euphrates” (Genesis 15:18). God changed Abram’s name to Abraham, to signify his role as the patriarch of many people, “For I have made you the father of many nations” (Genesis 17:5). God also changed Sarai’s name to Sarah.

During the wandering of Abraham’s family in Palestine, the shepherds of Abraham quarreled with the shepherds of Lot, so they decided to partition the land. Abraham and his people remained in the western highlands, while Lot and his family settled in Sodom near the Dead Sea. The people of Sodom and the nearby city of Gomorrah proved to be wicked and treacherous, so God rained brimstone and fire on the sinful cities, destroying them. Lot then moved to the eastern hills and became the ancestor of the people of Moab and Ammon in Transjordan.

Abraham also became the father of several other ancient peoples. Hagar, Sarah’s Egyptian slave, became Abraham’s concubine, as Sarah could not produce children because of her advanced age. Hagar gave birth to a child named Ismael, who would in time become the ancestor of all the Arab people. God promised Abraham another child. His beloved wife Sarah miraculously gave birth to a son, Isaac. Abraham then was a hundred years old and Sarah was ninety years old. God confronted Abraham with the ultimate test of faith by commanding him to sacrifice his son Isaac (or, according to Muslims, his son Ismael), and just as Abraham was about to carry out the order, God halted the sacrifice and rewarded him by renewing the covenant.

Isaac lived in the southern city of Beersheba. He married Rebecca, a young woman who was brought to him from his father’s family in the north. Rebecca gave birth to twins: Esau, the elder, a mighty hunter, was Isaac’s favorite; and Jacob, the younger, more sensitive and delicate, was Rebecca’s favorite. Rebecca presented Jacob to her dying blind husband as being Esau after she disguised him with a cloak of rough goatskin, to grant him the birthright blessing due to the elder son. When Isaac discovered his mistake, it was too late to do anything but to promise his son Esau that he would become the father of the Edomites (Genesis 27:39); thus another nation was established. In time Esau took a wife from the family of his uncle Ismael (Genesis 28:9), the ancestor of the Arabs.

Jacob fled to the north, to the house of his uncle Laban in Haran. On his way north, God confirmed Jacob’s inheritance: “I am the lord, the God of Abraham and the God of Isaac; the land on which you lie I will give to you and to your descendants I am with you and will keep you wherever you go, and bring you back to this land.” (Genesis 28:13–16)

Jacob stayed with his uncle Laban in Haran. He married Laban’s two daughters, Leah and Rachel, and fathered eleven sons—Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun, and Joseph—with his two wives and their two maid-servants. God then commanded him to return to Palestine. On his way back, while crossing the river, he was forced to wrestle with a mysterious figure. Whether it was an angel or God, the mysterious figure changed Jacob’s name to Israel (“He who struggled with God”), “for you have striven with God and men, and have prevailed” (Genesis 32:28). Jacob then proceeded to Palestine and camped near Shechem. He built an altar at Bethel, in the same place where God had revealed himself to him on his way to Haran. Rachel died as she gave birth to Benjamin, the last of Jacob’s sons. Joseph, Jacob’s favorite son, was detested by his brothers. They sold him to a group of Ismaelite merchants going to Egypt with a caravan of camels. The brothers claimed to their father that a wild beast had attacked Joseph. In Egypt, Joseph rose quickly in wealth and status and was appointed as the pharaoh’s grand vizier. In this high position he reorganized the economy of Egypt by storing surplus food from good years for future bad years. When Palestine was hit by famine, Jacob sent ten of his sons to Egypt for food. When they met the grand vizier Joseph, they did not recognize him, but eventually he revealed his identity to them. Jacob and his children then moved to Egypt to live with Joseph. On his deathbed, Jacob blessed all his children, and gave Judah the royal birthright (Genesis 49:8–10). And after his death his body was taken back to Palestine to be buried in the cave of Machpelah in Hebron.

The Historicity of the Narrative of the Patriarchs

Many of the early biblical archaeologists were clerics or theologians. They had a strong belief that God’s promise to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob was a real promise given to real people, not imaginary creations of an anonymous ancient scribe’s pen. People like the French archaeologist Ronald de Vaux and the American archaeologist William F. Albright insisted that the picture in Genesis was historical. These biblical historians and archaeologists were convinced that new discoveries would confirm that the Patriarchs were historical figures. They believed that the Bible narrated the history of Israel in sequential order, from the Patriarchs to Egypt, to Exodus, to the wandering in the desert, to the conqueror of Canaan, to the period of judges, and to the establishment of the united monarchy. 45

Albright argued that the collapse of the early Bronze Age urban culture in Palestine had been a sudden one resulting from an invasion of pastoral nomads from the desert in the northeast. He hypothesized that the invaders were the Amorites. He also dated the Abraham episode in Genesis to the second millennium. This “Amorite Hypothesis” did not last long, as excavations showed that the urban system had not collapsed suddenly, but declined over many decades as a result of economic, social, and climatic changes. As outlined in part I, the South Levant in the third millennium enjoyed favorable climate conditions that brought more than five hundred years of extraordinary prosperity to Palestine. During the second millennium, this prosperity started to decline as a result of devastating drought. So when the assumed Amorite migration westward from Mesopotamia toward Palestine was shown to be illusory, Albright and his colleagues tried to link the patriarchal narrative to the middle Bronze Age or the early Iron Age. Again this attempt failed to establish a convincing link. 46

During the 1970s, John Van Seters and Thomas Thompson suggested, in two detailed monographs, exilic or post-exilic dates for the entirety of the Patriarchal traditions, and argued against their affinity with any second-millennium BCE backgrounds. Their views became influential, and today most scholars indeed define the Patriarchal tradition as a late invention with no historical validity. 47

Most scholars believe that the patriarchal stories in Genesis are not related to the second millennium BCE, but are rather most likely related to the period of the compilation of the Bible in the seventh and eighth centuries BCE, based on the following points:

- The stories of the Patriarchs are packed with camels. It is well known that camels were not domesticated earlier than the first millennium. The camel caravan carrying “gum, balm, and myrrh” in the Joseph story would have been part of the Arabian trade that flourished during the Assyrian rule from the eighth to seventh centuries BCE.

- Gerar is mentioned in Genesis as a Philistine city. It has been identified with Tel Haror, northwest of Beersheba. Excavations in this region demonstrate that it was a small village in the early Iron Age.

- The Aramaeans, who dominated the stories of Jacob’s life in the north with his uncle Laban, did not become an important political factor in the region until the early ninth century BCE.

- In the story of Lot, two daughters served their father wine until he became drunk; they lay with him and eventually gave birth to two sons: Moab and Ammon. These two kingdoms were established between the eighth and seventh centuries BCE.

- In the story of Esau, Jacob promised his older son that he would become the father of Edom. Assyrian records indicate that there were no real kings and no state in Edom before the late eighth century BCE.

- Ismael, the scorned son of Abraham and Hagar, is described in Genesis as the ancestor of the Arab tribes who lived in the territories on the southern fringe of Judea. The Kedarites (descended from Ismael’s son Kedar) were mentioned in the Assyrian records of the late eighth century BCE. The Assyrian and Babylonian records of the eighth and sixth centuries BCE mention Ismael’s other sons: Adbeel, Nebaioth, and Tayma.

Taken in sum, the above incidents mentioned in the patriarchal stories in Genesis indicate that they were all composed around the same time, rather than being an actual historical account. 48

The Exodus

Jacob’s twelve sons and their descendants enjoyed a prosperous life under the protection of Joseph in the cities of the eastern Nile Delta. Over a period of four hundred years, they evolved into a great nation as God promised. “They multiplied and grew exceedingly strong, so the land was filled with them” (Exodus 1:7). But times changed and eventually a new pharaoh came to power “who knew not Joseph.” The new pharaoh enslaved them and forced them to build the royal cities of Pithom and Ramses. “But the more they were oppressed, the more they multiplied” (Exodus 1:12). The Egyptians made the Hebrews’ life bitter as they were forced into hard labor “with mortar and brick and in all kinds of work in the field” (Exodus 1:14).

The Egyptians became alarmed by the explosion of the Hebrew population, so the pharaoh ordered that all male Hebrew infants be drowned in the Nile. A child from the tribe of Levi set adrift in a basket of bulrushes was found and adopted by one of the pharaoh’s daughters. He was given the name Moses (meaning “to draw out of the water”), and was raised in the royal court. Years later, in adulthood, when he saw an Egyptian taskmaster beating a Hebrew slave, Moses killed the Egyptian and hid his body in the sand. He then fled to the wilderness, to the land of Median, where he started a new life as a desert nomad.

From the flickering flames of a burning bush, the god of Israel revealed himself to Moses as the deliverer of the people of Israel. He revealed his name, YHWH, and charged Moses and Moses’ brother Aaron with the task of returning to Egypt and demanding that the pharaoh free the Hebrews. The pharaoh, however, rejected Moses’s demands and intensified the suffering of the Hebrew slaves. God then told Moses to tell the pharaoh that YHWH would inflict a series of terrible plagues on Egypt if he refused (Exodus 7:16). But the pharaoh did not relent, and Egypt suffered from ten plagues: the Nile turned to blood; frogs, then gnats, then flies swarmed throughout Egypt. Boils and sores erupted on the skin of the Egyptians’ livestock. Hail rained down from the heavens, ruining the crops. Plagues of locusts and darkness then came upon Egypt. The final punishment, the tenth plague, was the death of all Egyptian firstborn, both human and animal.

Before the last punishment took place, God instructed Moses and Aaron to prepare for the Hebrew congregation a special sacrifice of lambs, whose blood was to be smeared on the doorpost of every Israelite dwelling so that the angel of death would pass over them on the night of the slaying of the Egyptian firstborn. When the pharaoh witnessed the death of the firstborn, including his own son, he relented and let the Hebrew slaves go. “About 600,000 men on foot, besides women and children” (Exodus 12:37) set out from the cities of the eastern delta toward the wilderness of Sinai. “God led the people round by the way of the wilderness toward the Red Sea” (Exodus 13:17–18). Later on, the pharaoh changed his mind and sent “six hundred picked chariots and all the chariots of Egypt” after the Hebrew people. The Red Sea parted to allow the fleeing Israelites to cross over to Sinai on dry land. And as soon as they had made the crossing, the towering waters drowned the pursuing Egyptians in an unforgettable miracle that was commemorated in the biblical Song of the Sea (Exodus 15:1–18).

Moses then guided his people through the wilderness. They faced extreme hardship, and suffered from thirst and hunger. They were expressing their dissatisfaction to the point of regretting departing from Egypt. Moses pled with God to help his people. God intervened, and helped calm and feed them; he rained bread from the skies, which the Israelites named “manna.” God spoke to Moses, “I have listened to the complaints of the Israelites. Now tell them: at dusk you will eat meat and at dawn you will eat your fill of bread; and you will realize that I am God, your God” (Exodus 16:1). Finally, they reached the mountain of God, where Moses had received his first revelation. God told Moses: “Climb higher up the mountain and wait there for me;

I’ll give you tablets of stones, the teachings and commandments that I have written to instruct them” (Exodus 24:2). So Moses climbed to the summit to receive the laws under which the Israelites should forever live. Moses was on the mountain forty days and forty nights. And when God finished speaking to Moses on Mount Sinai, he gave him two tablets of testimony, slabs of stone, written with the finger of God.

The people grew impatient after weeks of waiting for Moses to come down off the mountain, and they asked Aaron, “Make gods for us to lead us” (Exodus 32:1). So Aaron told them, “Take off the gold rings from the ears of your wives and sons and daughters and bring them to me.” He took all the gold and cast it in the form of a calf to worship. When Moses came back and saw the calf and his people celebrating their new god, his anger flared. He threw down the tablets and smashed them to pieces and melted the calf down with fire (Exodus 32:12).

God then spoke to Moses: “Cut out two tablets of stone just like the originals and engrave on them the words that were on the original tablets you smashed.” Moses cut two tablets of stone and climbed Mount Sinai. God said to Moses: “Now write down these words, for by these words I have made covenant with you and Israel.” Moses was there with God forty days and forty nights. And he wrote on the tablets the words of the covenant, the Ten Commandments. And when Moses came down the mountain, he conveyed to his people God’s Ten Commandments and the legislation of worship, purity, and dietary laws (Exodus 34:34–35).

The Israelites camped at Paran and sent spies to collect intelligence on the people of Canaan (Numbers 13). Upon their return, they reported details of the strength of the Canaanites, which frightened the Israelites. They revolted against Moses, begging to return to Egypt. So God determined that this generation did not deserve to inherit the promised land and must remain wandering in the wilderness for another forty years.

The final chapter of the exodus story takes place in Transjordan. Moses revealed to his people the laws they were required to obey if they were to inherit Canaan. This law, known as the second law, is contained in the book of Deuteronomy (which means the “second law” in Greek). Finally, at the age of 120, Moses appointed Joshua, son of Nun, to lead the Israelites, and then ascended to the summit of Mount Nebo and died.

The Historical Context of the Exodus

The biblical narrative dates the Exodus event to the thirteenth century BCE, in the time of Pharaoh Ramesses II. There is no mention of these events in the Egyptian records, whether in inscriptions on the walls of temples, tomb inscriptions, or in papyri. And there is no evidence of the presence of Hebrews in Egypt as a distinct foreign ethnic group living in a distinct area of the eastern delta during this period.

The Bible implies that the children of Israel lived in the land of Goshen (Genesis 47:27). The delta region throughout the second millennium hosted migrant workers from many places, including Palestine.

It is an understatement to say that hundreds of thousands of slaves escaping from Egypt at the time of Ramesses II and crossing the desert toward Palestine was unlikely. In the thirteenth century BCE, Egypt was a dominant power controlling the entire region. The road that crossed the desert between the delta and Gaza was protected by a sophisticated system of forts, granaries, and wells. These road stations enabled the Egyptian army to cross the Sinai Peninsula efficiently when needed. A large group of slaves would have been stopped long before they could cross the desert. 49

According to the biblical narrative, the children of Israel wandered in Sinai for forty years. Extensive archaeological work in the entire peninsula, including Mount Sinai, has failed to yield any evidence of the existence of the wandering Israelites at the supposed time of the Exodus in the thirteenth century BCE (according to Numbers 33). Kadesh Barnea is mentioned as the place where the children of Israel camped for thirty-eight of the forty years of their wandering (Numbers 34). Archaeologists identified this site as being the oasis of Ein el-Qudeirat in eastern Sinai. Repeated excavations in this area failed to provide any evidence of fleeing refugees in the late Bronze Age. Ezion Geber is another place mentioned in the Bible as a camping site. Its location was identified by archaeologists as being at the tip of the Gulf of Aqaba between the towns of Eilat and Aqaba. Excavations in this location between 1938 and 1940 revealed no remains related to the late Bronze Age. 50

The Bible mentions the Canaanite king of Arad attacking the Israelites and taking some as captives. With the help of Yahweh, the children of Israel destroyed all the Canaanite cities (Numbers 21:1–3). However, twenty years of excavations at the site of Tel Arad east of Beersheba failed to reveal any remains related to the late Bronze Age. Furthermore, the biblical account says the Amorite king of Hesbon tried to block the Israelites from crossing his territory on their way to Palestine (Numbers 21:21– 250; Deuteronomy 2:24–35; Judges 11:19–21). Excavations at Tel Hesban south of Amman reveal no evidence of a late Bronze Age city in this region. It is also mentioned in the Bible that the children of Israel, as they crossed Transjordan, were confronted by Moab, Edom, and Ammon. It is known now that the plateau of Transjordan was sparsely inhabited in the late Bronze Age. 51 As Amihai Mazar and Israel Finklestein state in their book, The Quest for the Historical Israel:

The Exodus story, one of the most prominent traditions in Israelite common memory, cannot be accepted as a historical event and must be de-fined as a national saga. We cannot perceive a whole nation wandering through the desert for forty years under the leadership of Moses, as presented in the biblical tradition. 52

The Conquest of Canaan

According to the book of Deuteronomy, Moses did not enter the promised land. Before his death and burial on Mount Nebo, he delivered God’s laws to his people and appointed Joshua as his successor to lead the Israelites.

God commanded Joshua to enter the promised land. Jericho was the first target, so Joshua marched around the high walls of the city for six days, and on the seventh day, the mighty walls tumbled down as the Israelites’ war trumpets blasted.

The next target was the strategic city of Ai, near Bethel, located on the main roads leading to the hill country. Joshua tricked the enemy by setting an ambush on the western side while having his main force in the open field to the east of the city. When the Canaanite army stormed out of the city to engage the retreating Israelite attackers, the hidden ambush unit entered the city and set it ablaze. Joshua then reversed the retreat; he slaughtered all of the city’s inhabitants and hanged the king from a tree (Joshua 8:1–29).

Following the victories in Jericho and Ai, the Gibeonites who inhabited four cities north of Jerusalem sent emissaries to Joshua pleading for mercy on the basis that they were foreigners and not the natives whom God ordered to be exterminated. Joshua agreed to make peace with them. But when he learned later that they were natives, Joshua punished them by declaring that they would always serve as “hewers of wood and drawers of waters” for the Israelites (Joshua 9:27).

The Canaanite kings of Jerusalem, Hebron, Jarmuth, Lachish, and Eglon formed a coalition and marched their forces around Gibeon. Joshua surprised the coalition forces and God pummeled them with great stones from the heavens. The sun was setting, but Joshua asked God to keep the sun standing still until the coalition forces were destroyed and divine will was fulfilled. The sun then “stayed in the midst of heaven, and did not hasten to go down for about a whole day. There has been no day like it before or since, when the Lord hearkened to the voice of a man; for the Lord fought for Israel” (Joshua 10:13–14). The fleeing kings were finally captured and killed. Joshua’s military campaign continued until all the cities in southern Palestine were destroyed.

The final chapter took place in the north. Joshua faced a coalition headed by Hazor in an open-field battle in Galilee that ended with the complete destruction of the Canaanite forces. Hazor then was set ablaze (Joshua 11:4–10).

The Historical Context of the Conquest of Canaan

Excavations at the sites of Beth Shan and Megiddo disclosed evidence of strong Egyptian influence in Palestine during the thirteenth and twelfth centuries BCE. 53 The Egyptian records of the late Bronze Age provide us with full information about the status of Palestine during that period. Most of the information is provided by the Tel el-Amarna letters sent to Egypt by the rulers of the city-states in Palestine, who were vassals of Egypt. These letters reveal that Palestine was an Egyptian province controlled by an Egyptian administration. Palestinian cities such as Jerusalem, Shechem, Megiddo, Hazor, Beth Shan, Gaza, Lachish, and Jaffa were weak, and were not protected by fortifications. Many cities became deserted or shrank in size, and the total population did not exceed 100,000. Pharaoh Ramesses II, the strongest of the pharaohs, would not have overlooked or ignored an event like the invasion of Palestine by a group of refugees. It is also unlikely that the destruction of so many vassal cities by the invaders would have been left unmentioned in the extensive Egyptian records.

The city of Jericho was unfortified in the thirteenth century. There was no evidence of a settlement in the city at that time. Thus the story of the Israelite forces marching around the walled town, causing the collapse of Jericho’s mighty walls by blowing war trumpets, must be an invention. 54

Archaeologists identified Khirbet et-tell as the location of Ai, northeast of Jerusalem. A French-trained Jewish Palestinian archaeologist, Judith Marquet-Krause, conducted extensive excavation work in this area between 1933 and 1935. She found no evidence of settlement at that location. Renewed excavations in the 1960s produced the same results. 55

Similarly, at el-Jib north of Jerusalem—identified by archaeologists as the site of Gibeon—no remains related to the late Bronze Age have been found. Excavations at the other three Gibeonite cities—Chephirah, Beeroth, and Kiriath-Jearim—revealed the same picture. The same is true in the cases of Arad and Hesbon, as mentioned previously. 56

The book of Joshua states that “the land had rest from war” (Joshua 11:23). It claims that all the Canaanites and the indigenous people were destroyed, and then the land was divided among the twelve tribes of Israel. However, the book of Joshua itself contradicts this claim, as it states that large territories remained to be conquered, including “all the regions of the Philistines” in the southern coastal plains, the Phoenician coast in the north, and the Beqa Valley in the northeast” (Joshua 13:1–6). The great Canaanite cities of the coastal plains and the northern valleys, such as Megiddo, Beth Shan, Dor, and Gezer, are listed in the book of Judges as uncaptured. The book also mentions that the Ammonites and the Moabites remained hostile, as well as the desert-dwelling Medianites and Amalekites. Furthermore, the book of Judges is full of stories of the wars between the Israelites and their neighbors (the most colorful of these is the saga of Samson, who was betrayed by the Philistine temptress Delilah).

Since the 1960s it has become obvious that the conquest of Canaan was not a historical reality. Archaeologists have concluded that many of the sites mentioned in the conquest narrative were uninhabited during the presumed time of the conquest in the thirteenth century BCE. It is now accepted by all scholars that archaeology has ruled out the conquest of Canaan as a verifiable historical event.

The Golden Age of the United Kingdom of David and Solomon

The transition from the period of Judges to the time of the monarchy begins with a great military crisis, described in 1 Samuel 4–5. The Philistine armies defeated the Israelites in battle and captured the holy Ark of the Covenant. The Israelites, under the leadership of the prophet Samuel, recovered the Ark and brought it back to Kiryat Yearim, west of Jerusalem. Following this military confrontation with the Philistines, the elders of Israel assembled at Samuel’s home and asked him to appoint a king for Israel (1 Samuel 8:10–18). God instructed Samuel to do as the people requested, and revealed to him his selection of Saul, son of Kish, to be the first king (1 Samuel 15:10–26). God also instructed Samuel to go to the family of Jesse from Bethlehem, “for I have provided for myself a king among his sons” (1 Samuel 16:1).

The Philistines waged another war against Israel, and the two armies faced each other in the valley of Elah in the Shephelah (lowlands) in the Judean desert. The giant warrior Goliath of the Philistines mocked the god of Israel, and challenged any Israelite warrior to engage in single combat with him. David, the youngest of Jesse’s sons, took up the challenge. He shouted at Goliath: “You come to me with a sword and with a spear and with a javelin; but I come to you in the name of the Lord” (1 Samuel 17:45). David then took a small stone from his shepherd’s pouch and slung it with deadly aim at Goliath’s forehead, killing him on the spot. The Philistines were routed. David, the new hero of Israel, befriended Saul’s son Jonathan and married Michal, the daughter of the king. David was popularly acclaimed Israel’s greatest hero—greater even than the king. The enthusiastic cries of his admirers, “Saul has slain his thousands and David his ten thousands!” (1 Samuel 18:7) made King Saul jealous. It was only a matter of time before David would have to contest Saul’s leadership and claim the throne of all Israel.

Escaping Saul’s murderous fury, David became the leader of a band of fugitives and soldiers of fortune, with people in distress or deep in debt flocking to him. David and his men roamed in the foothills of the Shephelah, and in the southern margins of the Judean hills—all regions located away from the center of power of Saul’s kingdom to the north of Jerusalem. Tragically, Saul’s sons were killed in battle with the Philistines far to the north at Mount Gilboa, and Saul took his own life. David proceeded quickly to the ancient city of Hebron in Judea, where the people of Judea declared him king. This was the beginning of the great Davidic state and lineage, the beginning of the glorious united monarchy.

Once David and his men had overpowered the remaining pockets of opposition among Saul’s supporters, representatives of all the tribes duly convened in Hebron to declare David king over all of Israel. After reigning seven years in Hebron, David moved north to conquer the Jebusite stronghold of Jerusalem—until then claimed by none of the tribes of Israel—to make it his capital. He ordered that the Ark of the Covenant be brought up from Kiriyath-Jearim.

David then received an astonishing, unconditional promise from God:

Thus says the Lord of hosts, I took you from the pasture, from following the sheep, that you should be prince over my people Israel; and I have been with you wherever you went, and have cut off all your enemies from before you; and I will make for you a great name, like the name of the great ones of earth. And I will appoint a place for my people Israel, and will plant them, that they may dwell in their own place, and be disturbed no more; and violent men shall afflict them no more, as formerly, from the time that I appointed judges over my people Israel; and I will give you rest from all your enemies. Moreover the Lord declares to you that the Lord will make you a house. When your days are fulfilled and you lie down with your fathers, I will raise up your offspring after you, who shall come forth from your body, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom. He shall build a house for my name, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever. I will be his father, and he shall be my son. When he commits iniquity, I will chasten him with the rod of men, with the stripes of the sons of men; but I will not take my steadfast love for him, as I took it from Saul, whom I put away from before you. And your house and your kingdom shall be made sure for ever before me; your throne shall be established for ever. (2 Samuel 7:8–16).

David then initiated sweeping wars of liberation and expansion. In a series of swift battles, he destroyed the power of the Philistines and defeated the Ammonites, the Moabites, and the Edomites in Transjordan, concluding his campaigns with the subjugation of the Arameans far to the north. Returning in triumph to Jerusalem,

David now ruled over a vast territory, far more extensive even than the tribal inheritances of Israel. But he did not find peace even in this time of glory. Dynastic conflicts—including the revolt of his son Absalom—led to great concern for the continuation of his dynasty. Just before David’s death, the priest Zadok anointed Solomon to be the next king of Israel.

Solomon, to whom God gave “wisdom and understanding beyond measure,” consolidated the Davidic dynasty and organized its empire, which now stretched from the Euphrates to the land of the Philistines and to the border of Egypt (1 Kings 4:24). His immense wealth came from a sophisticated system of taxation and forced labor required of each of the tribes of Israel, and from trading expeditions to exotic countries in the south. In recognition of his fame and wisdom, the fabled queen of Sheba visited him in Jerusalem and brought in a caravan of dazzling gifts.