In order to convey a better understanding of the history of Palestine under the Assyrians and the Babylonians, a narrative of the history of Mesopotamia is presented here. The political history of Mesopotamia can be summarized in the following timeline:

| 4500–4000 BCE | Rule by the Sumerians |

| 2700 BCE | Treaty with the Elamites |

| 3000–2000 BCE | The period of city-states and nation-states. The most important state is the one established by Sargon of Akkad in 2334 BCE; Akkadi rule lasts until 2112. |

| 2000–1500 BCE | The period of the several kingdoms. The most important kingdoms are the one established in Babylon by Hammurabi in 1792 BCE, the state established by the Kassites in Babylon, and the Assyrian state of Tiglath-Pileser I. The Babylonian empire lasts from 1830 to 1595 BCE. |

| 1365–626 BCE | The period of empires of Mesopotamia. The Assyrians take control; the Elamites are another power during this period. The most important of these are: • The Assyrian Empire under Assurnasirpal II (883 BCE) • Shamaneser III (858–824 BCE) • Tiglath-Pileser III (744–727 BCE) • Sargon II (727–705 BCE) • Sennacherib (704–681 BCE) • Esarhaddon (713–669 BCE) Assyria falls to the Persians in 610. |

| 586 BCE | The Neo-Babylonians and the Medes: the Neo-Babylonians exile the Jews. |

| 539 BCE | The Achaemenids (First Persian Empire): Cyrus the Great of Persia conquers Mesopotamia in 539 and sends the Jews home |

| 330 BCE | Alexander the Great conquers the Medes, ending the Persian Empire. |

| 323 BCE | Alexander the Great’s death. The Seleucids inherit a large portion of his empire, including most of the Achaemenid and Persian empires. |

| 245 BCE | Parthia takes over after the weakening of the Seleucid Empire. A period of instability follows, marked by a long series of battles between Rome and Parthia. |

| 226 BCE | The Sassanids and the Byzantines arrive; the Sasanian Empire (also called the Neo-Persian Empire) defeats Parthia and comes to power in 87 BCE. |

| 220 BCE–ca. 650 CE | The Persian Sassanids and the Byzantines fight long and bitter wars, opening the way for Arab rule. |

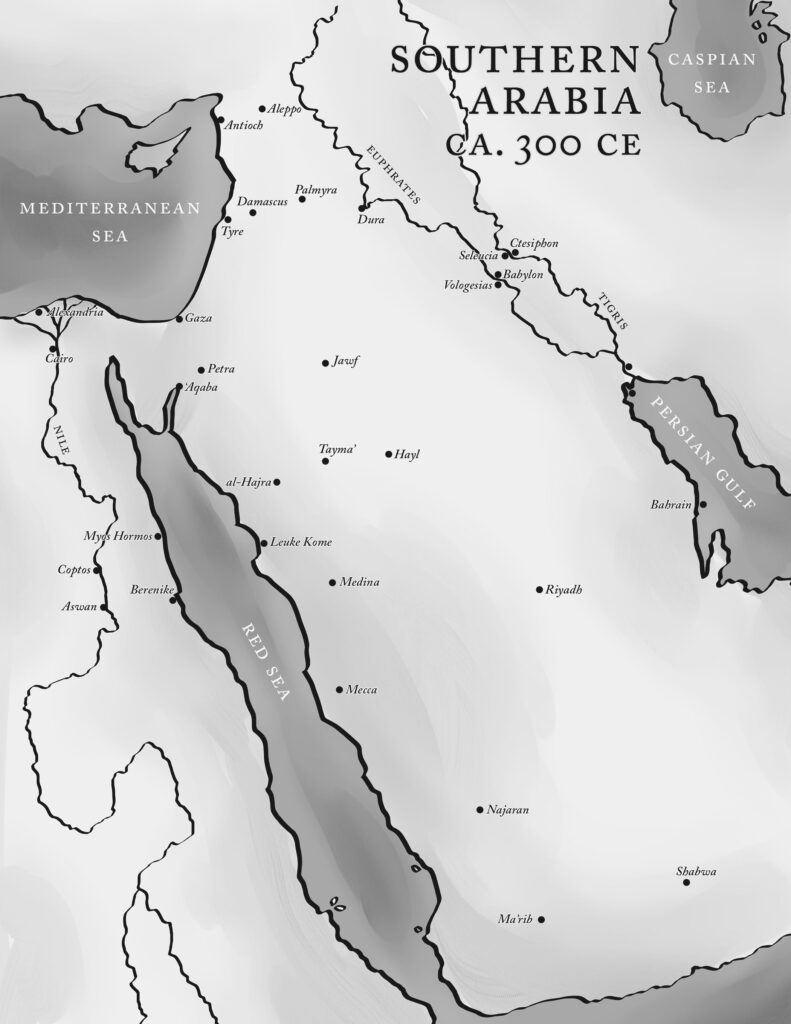

In Greek, the term mesopotamia means “[land] between the rivers.” Originally it referred to the flat plains between the Tigris and Euphrates. Over time, the term included all the plains and hills surrounding the rivers, corresponding to modern-day Iraq, Kuwait, and the northeastern section of Syria, as well as parts of southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran. Early scholars and historians assumed that Mesopotamia was the first part of the Near East to be settled. Most historians now believe that the Near East’s initial inhabited zone was the Fertile Crescent, a broad belt of foothills surrounding the Mesopotamian plains. The Crescent ran from central Palestine northward through Syria and eastern Asia Minor, then turned eastward to include northern Iraq and Iran. As early as 9000 BCE, this region witnessed the beginnings of agriculture and raising livestock. Over time, agriculture and herding stimulated population growth and the establishment of many settlements. By the eighth millennium BCE (7000 BCE), some of these settlements had grown larger and became towns.

Between 6000 and 5500 BCE, some of the inhabitants of the villages and towns began moving southward onto the plains of Mesopotamia. The exact reasons for the migrations are not clear. Several theories have been postulated; the most recent was proposed by a group of scholars at Columbia University who attributed these movements to a huge natural catastrophe. William Ryan and Walter Pitman postulate that the Black Sea was a closed lake, not connected to the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas. A huge natural dam, the Bosporus, separated the lake from the two seas. The catastrophe occurred around 5600 BCE, when this dam burst and allowed an enormous amount of salt water to enter the lake, which was hundreds of feet below sea level, flooding its shores for many kilometers. This disaster coincides with the time when migrations started. The historians also speculate that this catastrophe was behind the legends of the great flood that are mentioned in the ancient Near Eastern texts. 79

The most significant immigrant group who settled in Mesopotamia were the Sumerians, who settled in the flatlands just northwest of the Persian/Arab Gulf between 4500 and 4000 BCE. The Sumerians probably controlled the region after they conquered the farmers and hunters who already lived there.

Once the Sumerians controlled southern Mesopotamia, they began developing the most advanced agricultural community in their new land. They were extremely intelligent adventurists who created new methods of irrigation which turned their lands into a Garden of Eden, and over time they developed the first high civilization in human history. As Yale University scholar Karen R. Nemet-Nejat says, “The Sumerians turned an agricultural community into the first urban civilization in the world.” 80 They invented the brick mold and devised many tools, skills, and techniques: the potter’s wheel, the wagon wheel, the plow, the sailboat, the arch, the vault, the dome, casting in copper and bronze, and many other inventions. They invented a system of writing on clay which was adopted by people all over the Near East for more than two thousand years. They made significant advances in arts, literature, medicine, religion, and law. They valued personal rights and resented any encroachment on them. 81

The Sumerian writing system, known as “cuneiform” (wedge-shaped) writing,

was composed of nearly six hundred separate cuneiform signs. Thousands of clay cuneiform tables were discovered which contained administrative and financial records as well as religious literature and myths. They also contained historical records related to Sumerian kings, their wars, and their achievements.

The Sumerian agricultural communities were dependent on a complex irrigation system which required a strong spirit of cooperation and commitment to the interests of the entire community. This was the foundation of the advanced governmental institution and the birth of the city-states. It was also behind the development of trade and the creation of a strong military force. The Sumerian cities were not just large, populous towns but also true city-states, each city representing a cohesive political unit controlling a large expanse of farmland and supporting villages. Competition and sometimes war dominated the relationship between these cities. Uruk and Eridu were among the first to be established. These two cities and several others, including Lagash, Ur, Larsa, and Nippur were engaged in commerce, trading, and different industries. Some of the trade routes extended northward into Akkad in central Mesopotamia. Akkad was not as prosperous as Sumer. Competition among the cities of both regions dominated the political scene until a strong political-military ruler of one of the cities took control and created the world’s first known empire. This ruler was Sargon of Akkad, who in 2334 BCE created the first known empire in the world.

Sargon was a royal official in Kish when that city was captured by the Sumerian king of Uruk. Sargon and other officials of Kish escaped and moved north to Akkad. They were able to form a coalition of many cities in Sumer and Akkad, and raised a strong army. Sargon marched onto Kish and defeated the Sumerian king of Uruk, then attacked and seized control of the other city-states one by one. After his armies reached the gulf in the southwest, he turned northward into Syria. Sargon’s empire did not last for long; his successors failed to defend Akkad and Sumer against the Gutians and Elamites of Persia and the Amorites of Syria.

In about 2112 BCE, the Sumerian king of Ur established a new dynasty to rule the region; however, this dynasty did not last for long either, and Mesopotamia returned to its previous status of multiple city-states.

In 1813 BCE, Shamishi-Adad, a military leader in the city of Ashur, overthrew the ruler of the city and established a new dynasty which controlled all of Mesopotamia and expanded its control into the Syrian city of Mari.

In 1850 BCE, a new dynasty was established in Babylon under the leadership of Hammurabi, who seized many cities: Eshnunna, Ashur, Nineveh, and others. Hammurabi dedicated great efforts to constructing new irrigation channels, building shrines, and encouraging artists, writers, and educators. He was known as a strong ruler who established law and order. He issued a harsh law code under which many offenses were punished by death. During his reign, Babylon was a prosperous state. The kingdom of Babylon under Hammurabi’s heirs did not last for long, however. By 1700 BCE, Mesopotamia was back to being a coalition of city-states.

In 1595 BCE, the forces of Hatti, in Asia Minor, marched on Babylon and destroyed the city, but they withdrew their forces shortly after their victory. The Kassites of the mountainous region of eastern Iran then marched into southern Mesopotamia and occupied Babylon. Within two or three generations, they had assimilated with the inhabitants of Babylon and become Babylonized. The Kassite rulers of Babylon managed to bring most of the city-states of southern and central Mesopotamia under Babylonian control, thus building a stable and prosperous empire that lasted more than four centuries.

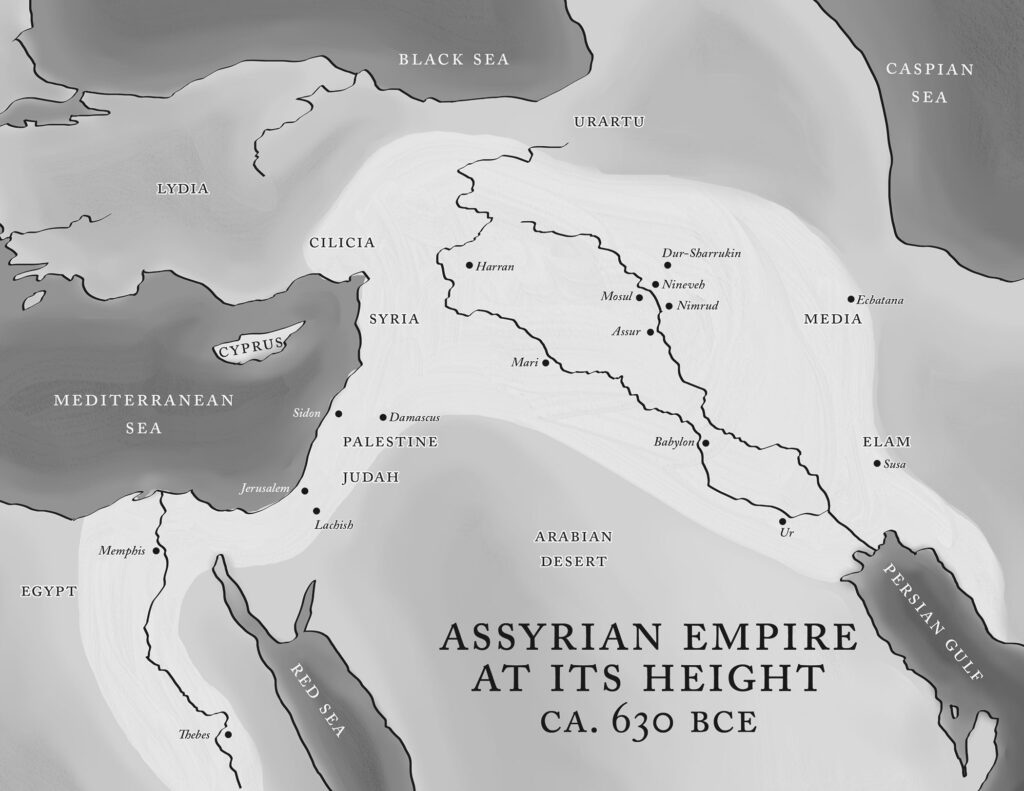

In 1365 BCE, an aggressive Assyrian king, Assuruballit I, established a new Assyrian kingdom that ruled over all of Mesopotamia. Under Tiglath-Pileser (1115–1077 BCE), Assyria turned into an empire that included significant parts of Syria. This empire had many strong and effective rulers. By 630 BCE, the Assyrian Empire included many territories: western Persia, eastern Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt.

Palestine under Assyrian Rule (841–612 BCE)

Assyria started campaigning to expand its empire in the ninth century BCE. The Assyrians were able to control Hatti and Amurru; then they marched against Syria. An impressive coalition of Levantine states—Damascus, Hamath, Israel, and various Phoenician city-states—confronted the Assyrian forces of king Shamaneser III (858–824 BCE) at the battle of Qarqar in 853 BCE. Although the coalition was defeated in this battle, the Assyrians were unable to advance further due to the fierce resistance of the coalition forces. In 841 BCE, Shalmaneser returned and was able to capture Damascus, and from there marched south into Palestine, capturing Samaria, the capital of the city-state of Israel. The Assyrian forces then marched through Palestine, controlling all its regions: Phoenicia, Ammon, Moab, Judea, Edom, Ashqelon, and Gaza.

As Assyria began expanding its authority over Palestine, it started a policy of subordinating these states and managing them as vassals. Their economies were integrated into the international trade of the Assyrian Empire. In 733 BCE, the Assyrian king Tiglath–Pileser III (744–727 BCE) annexed Damascus as a province. He also had a strong grip and a direct control of the Jezreel. Rulers and states who were compliant with Assyria’s interest were allowed to survive intact as clients of the empire. Those who resisted faced systematic destruction followed by deportation of the population. The deportees were settled in Assyrian cities or other parts of the empire. Several hundred thousand people were transported across the extent of the empire. These large-scale deportations caused the collapse of indigenous regional infrastructures. Vassal states were able to maintain their social infrastructures. In 731 BCE Samaria, as an Assyrian vassal, was given control over the fertile lands of the vast Jezreel Valley. This autonomous status lasted for less than a decade and ended in 722 BCE, when Sargon II (727–705 BCE), king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, seized the city, destroyed its infrastructure, and deported its population to Syria and Assyria. Different groups of people were brought to Samaria from other parts of the empire. Samaria then became a new Assyrian province, governed by an Assyrian officer. 82

The next Assyrian target was the southern highlands. Lachish dominated the region and controlled its olive industry. In 701 BCE the Assyrians launched their attack on Lachish. The city was destroyed and burned, and the entire population was deported. The coastal towns were annexed, and the olive industry was reorganized.

The Assyrians named the whole southern region Judea, and made Jerusalem its capital. Jerusalem played a major role in the new reorganization of this region. It supported Assyrian policies and became an Assyrian vassal. By the mid-seventh century Jerusalem had grown to a city of 25,000 people, becoming the political and economic center of the south.

Assurbanipal, who ruled between 668 and 627 BCE, was the last great Assyrian king. In 626 BCE, a Chaldean prince seized control of Babylon and established the Chaldean (Neo-Babylonian) dynasty. In 612 BCE, the coalition forces of the Neo-Babylonians and the Medians swept into Assyrian heartland, taking town after town and finally capturing Nineveh. By 610 BCE the Assyrian throne and government had ceased to exist.

After the fall of the Assyrian capital Nineveh in 612 BCE, Egypt marched into southern Palestine and occupied Judea in 609 BCE. In 605 BCE, The Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar defeated the Egyptians at Carchemish, and four years later defeated them again at Gaza.

Palestine under Babylonian Rule (626–539 BCE)

In 612 BCE the Assyrian capital at Nineveh was captured and then burned by the coalition forces of the Medes and the Babylonians. The imperial government of Assyria survived for a short time in Haran. However, the Babylonians succeeded in taking Haran and then marched against the Egyptians in the south. In 605 BCE Nebuchadnezzar’s forces defeated Pharaoh Neco at the battle of Carchemish on the Syria-Anatolia border. With this decisive victory, Syria and Palestine became open for the Babylonians, and over the following few years they asserted their claim as Assyria’s successors.

In 597 BCE Jerusalem surrendered to the Babylonians and became a vassal state, like all other Syrian and Palestinian cities. However, the Egyptians continued to pressure the state of southern Palestine to resist Babylonian rule. In 588 BCE, Jerusalem allied itself with Egypt and revolted against Babylon to regain its independence. This action prompted the Babylonians to march their army toward the city, which was placed under siege until it fell in 586 BCE.

Babylon followed Assyria’s policy toward the defeated countries. This policy was based on population relocation, resettlement, and reconstruction. The rulers and the upper classes were deported to regions in the heart of the empire, along with the skilled laborers. Rebels and potential troublemakers were severely punished or killed. Large-scale population resettlement was a long-term solution for potential rebellions. The resettlement of new people in the great cities of the empire and in the villages and towns of foreign territories assured their allegiance to the empire. They served as a counterbalance against any local opposition to the government. This population

resettlement program was backed by extensive political propaganda. Conquering a new territory was presented as liberating its people from former oppressive rulers. Deportation was presented as a reward for populations who rebelled against their leaders. The deportees received land and enjoyed a prosperous life in their new cities. They were also given support and protection against the indigenous population, who viewed them as intruders. The ultimate goal of this policy was to create an imperial citizenry that was faithful and dependent on the empire. This Babylonian policy was applied to Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar after its defeat in 586 BCE. The city suffered a lot of destruction by the victorious army, but was not completely destroyed. Deportation of the population was carried out according to the above-stated policy. The king and the leaders of the city were exiled to Babylon along with the elites and skilled laborers. It is worth noting that, for the most part, the “people of the land” (am-hares) were allowed to stay. Some were deported to other parts of the empire. People from other regions were resettled in Palestine’s southern highlands, much like what happened in Samaria around 722 BCE. Cities were not completely destroyed, nor were entire populations deported. 83

According to data collected during intensive surveys and excavations, at least 75 percent of the population of the southern hills remained on the land, continuing their normal agricultural life as before. The city of Jerusalem was affected the most during the conflict. Bethel and Gibeon, north of Jerusalem, continued to be inhabited, as well as the area south of Jerusalem around Bethlehem. Misshape, near modern Ramallah, was not destroyed; in fact, it became the capital of Judea. The population that remained in the country did not just consist of the poor villagers—it also included artisans, scribes, and priests. 84

After the defeat of Jerusalem, the Babylonians installed Gedaliah, the grandson of King Josiah’s secretary in Mizpah, as governor. They also distributed the lands of the deportees to the poorest and most exploited sector of the population. In 582 BCE officers of the old army assassinated Gedaliah, but their coup failed.

In Babylon, the exiles lived in the capital city and in the nearby countryside. They established new lives for themselves and became well integrated into Babylonian society. They were allowed to meet freely, buy land, and establish businesses. Many became prosperous and respected merchants. 85

In the autumn of 539 BCE, the Persian army defeated the Babylonians at Opis on the River Tigris. A month later, Cyrus entered Babylon and was enthroned as the representative of the god Marduk. The conquest of Babylon by the Persians resulted in the inheritance of the territories of Greater Syria, which included Palestine.

The Origins of the Persian Empire

Thousands of years ago, Central Asia was the origin of waves of nomadic migration into Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia. The earliest of the peoples who migrated were the Dravidians, who established themselves on a broad arc of territory that extended from the Indus River in what is today Pakistan through Iran, Anatolia, and perhaps all the way to Italy. The Etruscans, the rivals of Rome, probably were part of this wave.

The next major wave of migration was the nomadic people who are known as the Indo-Europeans, which occurred around four thousand years ago. The Indo-Europeans are known as the peoples who domesticated the horse. This accomplishment enabled them to move rapidly over vast distances and gave them overwhelming military superiority over sedentary peoples. Mounted on their horses or using carts pulled by horses, they were able to spread over much of Asia and Europe beginning about 2000 BCE. 86

The horse played an important role in the life of the Indo-Europeans. It was their “magical animal” or totem. One of the great nomadic groups who invaded Europe, the Goths, took their name from their word for horses; another group, ancestors of Persians, used personal names derived from their word for horses. The horse was one of three developments that enabled the Indo-Europeans to shape world history. The second of these innovations was the wheeled chariot, which came into use sometime around 1800 BCE. The third was the bow, the weapon that would dominate warfare for nearly three thousand years. Its later adaptation, the crossbow, was regarded as such a lethal weapon that when it was introduced into Europe in the twelfth century CE, the church banned its use for warfare among Christians. 87

The Indo-Europeans who migrated in 800 BCE to the territories south of the Caspian Sea along the Elbruz Mountain chain became known as the Persians. It is believed that they migrated from what is now northern Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan, an area that became known as Aryana Vaejah (the homeland of the Aryans). As they reached the northern part of what today is Iraq, they were forced to move east by the Assyrians. One group, known as the Medes, settled in what is now northern Iran, while other tribes moved further south to the hinterlands of the Persian Gulf, an area that the Greeks called Persis and that they themselves called Persia. The new immigrants settled in the low valleys and along the rivers, where they could farm and herd animals, and over time they were assimilated with the tribes who occupied the northern part of the country.

The kingdom of Elam was the dominant power in western Iran from the second millennium BCE until the mid-first millennium, when the Medes and the Persians established their states. Khuzistan and Fars were the main Elamite settlements, and the cities of Anshan and Susa were the centers of Elamite civilization. As Susa was on the eastern edge of Babylonian plains, its history was intertwined with that of its Mesopotamian neighbors. The Elamite kings held the title “King of Anshan and Susa.” Competition between Elam and Assyria dominated the political and economic scenes for control of the trade routes through the Zagros Mountains; however, there was a rich network of cultural ties, including close links between the Assyrian and Elamite royal families of the seventh century BCE. Although the Assyrians were the main dominant military power in the region, they never were able to control Elam completely. The Assyrians carried out multiple military campaigns against Elam, the most serious of them in 646 BCE, in which the forces of Ashurbanipal sacked Susa. 88 The Medes dominated northwest Iran. The Assyrians carried out multiple military campaigns against them, aiming to control the commercial routes and capture horses. By the end of the eighth century, many areas of Media, especially along the Great Khorasan Road, were incorporated in the Assyrian Empire. The Median city-lords in the territories controlled by Assyria were bound to the Assyrian king by loyalty oaths. 89

The Medes played a major role in the fall of the Assyrian Empire. The Median and Babylonian forces sacked the city of Nineveh in 612 BCE. The final battle between this coalition and the Assyrians took place in 609 BCE at Haran in northwestern Mesopotamia, where the Babylonian-Median coalition forces destroyed the remnant of the Assyrian army.

The Persian kingdom in Anshan was ruled by Cyrus I, the grandfather of Cyrus the Great. In 550 BCE, as the young king of Persia, Cyrus II conquered the Medes and expanded his kingdom to include Media. This victory was the beginning of a successful military campaign aimed at establishing the Achaemenid Empire, which controlled all of Mesopotamia. Their territory extended to the borders of Turkey (Anatolia) and Greece; they defeated the Babylonians and inherited the territories of Greater Syria and Palestine. Cyrus is credited with returning the Jewish exiles to Jerusalem in 538 BCE.

In 530 BCE Cambyses succeeded Cyrus the Great, inheriting a far larger empire than any that had previously existed. The most important achievement of Cambyses was his invasion of Egypt in 525 BCE, followed by the capture of Libya in the west and the kingdom of Kush in the south. 90 In 521 BCE, Darius I succeeded Cambyses, gaining the support of many influential officials in Persia, especially in the northern territories. During the reign of Darius I, the Persian Empire expanded further to the east, incorporating the Indus River Valley region (modern-day Pakistan and part of India), and incorporating a large area in Eastern Europe to the west. His forces crossed the narrow strait between the northern tip of the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea, sailing from the Black Sea to the Danube; his general Megabazus subjugated Thrace (southeastern Europe)and part of Macedonia. At its territorial height, the Persian Empire stretched from the Himalayas (Central Asia) to the Sahara (Africa), and from the Indus River Valley (the Indian subcontinent) to the Danube River (southeastern Europe). 91

Darius died in 486 BCE and was succeeded by his son Xerxes I, who took upon himself the responsibility of retribution against Athens, but first he had to deal with a revolt in Egypt which had begun before Darius’s death, and another in Babylon. Both revolts were crushed in 486 BCE. Xerxes then began a long campaign against Greece that was ultimately unsuccessful. He returned to Persia after assigning Mardonius to continue the military campaign in Greece. In the summer of 479 BCE, Athens was sacked for a second time. Between 479 and the early 460s BCE, the Athenians won several battles against the Persians.

In late July or early August 465 BCE, Xerxes was assassinated. He was succeeded by his son Artaxerxes I, who ruled for forty-one years. During his reign, Artaxerxes contended with a rebellion in Egypt. The rebels were supported by the Athenians. Persia was involved in several wars with the Greeks in the Aegean region and Anatolia. The relationship between Greece and Persia during Artaxerxes’ reign consisted of more than military conflicts; between wars it was dominated by a diplomatic relationship involving treaties and cultural exchanges, especially between Persia and Athens. Following the death of Artaxerxes in 424 BCE, his son Xerxes II ruled for just forty-five days. Between 424 and 331 BCE, several Persian kings ruled the empire: Darius II, Artaxerxes II, Artaxerxes III, Artaxerxes IV, and Darius III. During this period, the Persians continue to rule over vast territories. Unrest and rebellions continued from time to time; however, they were kept under control.

Palestine under Macedonian Rule (336–323 BCE)

In the late sixth and early fifth century BCE, Macedon was a Persian vassal. Macedonians were not Greek; however, the ruling family and elites were Hellenized, sharing cultural and political ties with their Greek city-state neighbors. Macedon was not a city-state, but a kingdom with extensive natural resources and manpower.

In the mid-fourth century, the Macedonian king Philip II (359–336 BCE) expanded his power in southeastern Europe after he built a strong army. Between the 350s and 340s he extended his influence into Greece, which was a collection of warring city-states. In 338 BCE, Philip II defeated Athens and the other Greek cities at the battle of Chaeronia. In 336 BCE, Philip II started his military campaign in Ionia. A force of ten thousand men crossed the Hellespont toward Abydos, which became the staging area for the Macedonian army.

In the summer of 336 BCE, when Darius III was king of Persia, the twenty-year-old Alexander III—who became known as Alexander the Great—succeeded his father Philip and became king of Macedon. While Philip was on his military campaign, Alexander stayed in Macedon, being tutored by the philosopher Aristotle and groomed for kingship. Between 336 and 334 BCE, Alexander consolidated his power in Thrace and Greece; in the spring of 334 BCE he led an army numbering between thirty thousand and forty thousand men and confronted Darius III at the Granicus River in northwestern Anatolia, ultimately defeating the Persians. This victory opened Asia Minor to the Macedonians. The garrison commander of Sardis, Mithrenes, voluntarily surrendered the city to the Macedonians. Alexander, who needed the Persian imperial bureaucracy to maintain a successful conquest, left Mithrenes in charge of the city. His progress through the rest of western Asia Minor followed the same pattern: those cities that gave themselves up willingly were “liberated” from Persian rule and subjected to Macedonian rule with no significant changes in their civic affairs. 92

Alexander faced Darius again in the autumn of 333 BCE and won another victory in the battle of Issus (in Anatolia), which opened the way to Phoenicia, giving the Macedonians access to the Persians’ main naval facilities. From Issus, Alexander marched south into Syria and Palestine. During the winter of 333–332 BCE, he captured Damascus, which was a critical center, as it was the place where many prominent Persian families had gathered, including Darius’ wife, mother, and several children.

Several important Phoenician cities, including Byblos and Sidon, surrendered without a fight; however, Tyre resisted for more than a year. As Alexander captured the Phoenician cities, he controlled the Persian fleet not only in Phoenicia, but also in Cyprus, Rhodes, and other important bases along the southern coast of Anatolia, which meant the end of Persian naval superiority.

Gaza, in southern Palestine, was considered the gate to Egypt; the city halted Alexander for two months. Historical records state that the inhabitants of Gaza continued fighting, street by street, even after the Persian garrison surrendered. 93

In November of 332 BCE Alexander reached Egypt, and the Persian satrap (governor) Mazaces surrendered the satrapy of Egypt to Alexander. At Memphis, the Egyptians crowned him as their pharaoh with the traditional double crown of the pharaohs. Then he spent a whole year organizing the country, during which he founded the city of Alexandria.

The defeat of the Persians in the battle of Issus shocked the Jews of Jerusalem, who had been loyal vassals of Persia. According to the Jewish historian Josephus Flavius, the high priest refused at first to submit to Alexander. The Macedonians promised that the Jews would continue to be governed according to their own law.

Alexander faced a revolt in Samaria against the governor he appointed. The revolt was crushed and the rebels were punished swiftly. Alexander’s march through Samaria toward Mesopotamia set the stage for the last decisive battle against Darius on October 31, 331 BCE. Defeated, Darius fled the field and withdrew to Ecbatana in the northern Zagros Mountains, intending to form another army from the upper satrapies. 94

Darius’ decision to withdraw to the north left the way open for Alexander to march on Babylon, Susa, Pasargadae, and Persepolis. In October of 331 BCE, Alexander was hailed as “King of the World” in Babylon. Alexander paid respect to the Babylonian god Marduk and his temple. The Persian governor of the city and province of Babylon, Mazaeus, was confirmed as a governor in conjunction with a Macedonian troop commander. In December of 331 BCE, Alexander was similarly received by Susa. 95

In the first few months of 330 BCE, Alexander faced a difficult road from Susa to Persepolis, but both Persepolis and Pasargadae surrendered in mid-January of 330 BCE. The treasuries of both cities were transferred to Susa. Alexander then visited Cyrus’ tomb to pay his respect to the empire’s founder. He thereafter turned his forces north toward Ecbatana in pursuit of Darius III.

In the midsummer of 330 BCE, Alexander continued his drive for the eastern provinces to control all of the Persian Empire and beyond, reaching India in 326 BCE. Only a mutiny by his army stopped him from going further east. He died in Babylon of a fever in 323 BCE. In building his empire, Alexander influenced the history of Europe, Africa, and Asia as he introduced Hellenism to the Middle East and opened the world of that time to trade and social interaction.

The Macedonians combined Syria and Palestine into one province with Samaria as its capital. Alexander continued the old imperial policies of deporting people to secure his provincial capital against rebellion. He deported a portion of Samaria’s population to other parts of the empire and resettled Macedonians in the city. He brought teachers, architects, and craftsmen to Palestine. The Greek language, art, and philosophy were used to create citizens loyal to their new rulers. Hellenism had been penetrating the Near East for decades before the triumph of Alexander. The coastal cities of northern Palestine (Phoenicia) had been affected by the Hellenistic culture through trade.

Palestine under Seleucid Rule (323–255 BCE)

After the death of Alexander, fighting broke out among the leading generals for control of the empire. For the next two decades, the lands conquered by Alexander witnessed many battles between the generals who succeeded him. Palestine was continuously invaded by armies on the march from Asia Minor or Syria to Egypt. During these years Jerusalem was conquered no less than six times. 96 Ultimately, the empire was divided into four kingdoms: the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt, ruled by Ptolemy I; the Cassander Kingdom in Macedonia, ruled by Cassander; the Kingdom of Lysimachus (a coalition of Greek cities, including Athens), ruled by Lysimachus; and the Seleucid Empire, ruled by Seleucus I Nicator.

The Seleucids inherited a larger portion of Alexander’s empire; their lands extended from Anatolia in the west to the borders of India in the east. They held most of the Achaemenid Empire except for Egypt, southern Syria, and parts of Asia Minor. The part of Alexander’s empire that the Seleucids controlled was extremely wealthy due to the trade routes that ran through it and the natural resources it was endowed with.

The Seleucids adopted the basis of the Achaemenid system of administration, but they founded new cities and rebuilt some of the old ones under new names. These were managed along the lines of the Greek polis, with its assembly of peoples, its council, and its officials appointed annually. Seleucus built two capitals: Seleucia (now Baghdad) on the Tigris in Mesopotamia, and Antioch, on the Orontes in Syria. Greek colonies were founded as far east as Bactria (Afghanistan), and the Greek culture spread throughout all of Iran. Greek became the official language, but it did not replace Aramaic, which had been the official language of the Achaemenid Empire; both languages were used in official transactions. Greek was the language of the upper classes, and appeared to replace the Aramaic at that level. Hellenization took place; however, it was not forced on the Persians. At the same time, Persianization of some Greek territories took place due to the intermingling and intermarriage of the two peoples. 97

The vast Seleucid Empire was made up of various Iranians and non-Iranians. As

a result, it was extremely difficult for the Seleucids to keep the eastern part of their empire united. By the middle of the third century BCE, the Seleucids had lost control over Bactria and Parthia. Andragoras, the satrap of Parthia, declared his independence in 245 BCE, and Diodotus, satrap of Bactria, declared Bactria’s independence in 255 BCE.

Palestine under the Parthian Empire (160 BCE–216 CE)

Shortly after the Bactrian Greeks declared their independence, the Parni tribe, a group of Scythian Dahae nomads who lived in the region between the Caspian and Aral Seas under the leadership of Arsaces, defeated the local Seleucid forces and took control of Parthia. About the same time, Arsaces’ brother, Tiridates (Tirdad), was able to take control of another region, Hyrcana (Gorgan). A new capital named Arshak (now known as Ashkhabad, the capital of Turkmenistan) was built for the new kingdom. The new kingdom, which became known as the Arsacid Kingdom or the Parthian Empire, expanded gradually in the second century BCE to include the entirety of Achaemenid Persia. 98

The ruler who established the Parthian Empire as a great power was Mithridates (Mehrdad), who conquered Media, Babylon, and Seleucia between 160 and 140 BCE. He then built a new capital, Ctesiphon, very close to Seleucia, east of the Tigris River (south of what is now Baghdad). He was compared to Cyrus the Great by Iranian historians; hence they gave him the Achaemenid title “King of Kings.” During this period, the Parthian Empire extended further east to include the Graeco-Bactrian kingdom.

The Parthian government was a decentralized feudal system in which power was distributed among many lords. The empire was composed of a collection of eighteen semi-autonomous kingdoms. These kingdoms paid tributes and taxes to the center and contributed military forces whenever there was an external war. Although there were always armed men both at the center and the vassal states, there was no central army ready at all times; forces were called up from across the empire in times of war. In their wars, the Parthians depended on light cavalry—mounted archers who were known for their mobility and maneuvering abilities. The early Islamic historians described the Parthians as Muluk al-Tawa’f, the “Kings among the Tribes.”

Within the empire there were sixty autonomous Greek settlements. The Parthians allowed the different cultures to strive and to work together rather than against one another. In other words, the political structure was built on the principle of unity based on diversity. Mithridates I established a Parthian senate, a council composed of members of the royal family and a group of advisers from different regions of the country. Mithridates also created a constitution that laid down the foundation of constitutional monarchy. 99

Between 140 and 53 BCE, Parthia faced many challenges from the west and north from the Seleucids, the Romans, and the Armenians, as well as nomadic invasions from the east, especially from the Scythians. During this period, several kings ruled the country. Among the most effective of these was Mithridates II, who took over the realm in 123 BCE; he was compared to Darius I. King Orodes II, who took office around 58 BCE, was very effective; during his reign, Marcus Licinius Crassus, the Roman governor of Syria, marched with a vast force toward Parthia. In 53 BCE, the Iranian general Sorena (Suren) broke Crassus’ army in the battle of Carrhae (Haran), capturing ten thousand Roman soldiers and killing and wounding twenty thousand more, including Crassus himself.100

The battle of Carrhae was one of the most humiliating defeats that the Roman army had ever suffered. It was the first time that Roman and Parthian armies had met each other on the battlefield, and it was a perfect demonstration of two different military machines of the ancient world.

The next Roman invasion took place in 37 BCE, when Mark Antony marched against the Parthians with one of the largest armies ever to be assembled. As winter was approaching, Mark Antony decided to end this expedition and to return to Syria. He went back in the spring of 34 BCE; however, this second campaign against Parthia was of minimal value; it only served to save face for Mark Antony. When Octavian came to power in 30 BCE, he followed a policy of diplomacy with the Parthians that enabled him to retrieve the eagle standards of the legions that had been lost at Carrhae. This friendly relationship allowed the Parthians to expand their empire in the east. War erupted again in 58 BCE during the reign of Nero, ending in a treaty whereby Rome and Parthia agreed to establish an independent Arsacid dynasty in Armenia as a buffer state. The treaty gave the Parthians the right to select future kings of Armenia subject to Roman approval.

The peaceful relationship between Rome and Parthia lasted a relatively long time, until the reign of Trajan, who found a pretext for war when the Parthian emperor, Vologases III, deposed the king of Armenia and appointed a new king without getting Rome’s approval. He marched as far as the shore of the Persian Gulf. His war ended in 116 CE, when he got ill. The conflicts continued with subsequent Roman emperors until 216 CE.

The wars between Rome and Parthia make for an engaging story, but like any good story, these wars also offer great lessons to learn from. Neither Rome or Parthia was able to prevail over the other for any length of time, regardless of what devices they used or what strategy they applied. Seeking profit and protecting the interest of the ruling elites was the motivation for war on both sides; when all attempts by either side to reach a decisive victory failed, they resorted to diplomacy to protect their interests. The interests of ordinary people were never the determining factor in their decision-making. As in most imperial countries, the two ancient superpowers of Rome and Parthia maintained steep social inequality, which led to unrest and instability. “This is why it could be said that for all their power, politics and wealth, it was glaring inequalities in these societies which ultimately destabilized Rome’s and Parthia’s vast empires and hastened their demise.” 101

Palestine under Roman Rule

Rome and the Italian peninsula were ruled by the Etruscans, who originated somewhere north of the Black Sea and settled in the northern part of the Italian peninsula. It is believed that the city of Rome gained its independence at the end of the sixth century BCE.

At the beginning, Rome was a society of agriculturists ruled by a hereditary elite of “patrician” families. Rome benefited from its strategic location on the last crossing on the Tiber River before the sea, which allowed the city to control the trade routes. During the early stage of the history of Rome, the city resembled the Greek city-states, and was known as the Republic; however, Rome at that time, unlike Athens, was not a democratic republic. The Senate was controlled by elite families who used their political control to enhance their social and economic position at the expense of the peasants. The Senate in this system appointed a consul to be the head of the state.

Rome expanded its control over all of Italy and beyond through military means. The greatest challenge Rome faced in its expansion wars was that of the city of Carthage, the powerful Phoenician city in what is now Tunisia, in North Africa. The fight between the two cities, known as the Punic Wars, was a long one. At one point the Carthaginian general Hannibal crossed the Alps from the north and invaded Italy. At the end, in 146 BCE, Rome won the war and destroyed the city of Carthage. Although the peasants (“plebeians”) bore the brunt of the fighting, they did not control the army and did not benefit from the victories; the elites controlled most of the conquered territories. Over time the peasants’ situation worsened, which led to a sort of mutiny and refusal to join the army. This form of struggle between the two classes resulted in the plebeians gaining some seats in the Senate. These were held by their leaders, but the poor masses gained almost nothing.

The wars produced a new source of wealth for the rich through the exploitation of the captives who were enslaved. The big landowners who could buy slaves cheaply used them to cultivate the land rather than employing the landless peasants. The slave population grew massively, and by the first century BCE there were two million slaves, compared with the free population of 3.25 million. Slave labor led to further impoverishment of the free laborers. The poor peasants could not provide their families with the main necessities of life, and many of their children ended up in the slave markets. The resulting class polarization led to a new wave of civil unrest which was much bloodier than the previous one. This period also witnessed several slave revolts, the most significant being the revolt of Spartacus in 73 BCE. This was the background against which Julius Caesar marched his army toward Rome in 49 BCE to put an end to the republic era and to establish a dictatorship leading to a new era: that of the Roman Empire. 102

The era of the empire is characterized by the dominance of the emperor over the Senate. The Senate became dependent on the emperors to maintain stability and to control the poor masses. The civil wars over social issues were replaced by civil wars between generals. Augustus became the first emperor in 31 BCE. The members of the wealthy class accepted monarchy as the only way to reestablish political stability. Augustus provided the rich the stability that protected their interests, and at the same time presented himself as the friend of the poor by providing them with cheap or even free grain, paid for with a small fraction of the taxes collected from the conquered countries. After Augustus’ reign, the rich on several occasions conspired against emperors, and when they succeeded, they selected a new emperor rather than re-establishing the republic.

The prosperity of the empire that has been claimed by historians was the prosperity of the rich in Rome, the other Roman cities, or the rich Roman communities in conquered territories. This prosperity manifested itself in rebuilding the cities on a lavish scale with temples, theaters, stadia and amphitheaters, gymnasia and baths, markets, aqueducts and fountains, and palaces and administrative buildings. All this, however, was achieved at the expense of the colonies, where the Roman administration established a brutal system of oppression. The farmers in the colonies were subjected to an intolerable tax system savagely enforced by Roman soldiers. The emperors relied on a strong professional army, made up mainly of mercenaries. The poor in Rome were pacified by the cheap food provided by the emperors. 103

The contribution of the Romans to civilization was limited to constructing buildings for the rich and the administrators, and paving roads for the purpose of moving Roman armies rapidly. The Roman Empire added little to humanity; it was not characterized by innovation in the same way as early Mesopotamia and Egypt or Greece. The Romans were originally a barbarian nation who adopted Hellenistic culture. They became wholehearted Hellenists. They abandoned their crude culture and followed the Greek one. However, they continued to be Romans, despite the brilliant Hellenistic literature they produced. They continued to convey themselves as a warlike, powerful nation; their legend of the twin sons of the god of war, Romulus and Remus, remained the symbol of Rome. The conquered nations, including the Palestinians, associated the Romans with savage oppression, crucifixion, and gladiatorial combat. 104