From its earliest history, the population of Palestine was enriched by numerous cultural influences arising from immigration, trade, and warfare. Among the groups that influenced Palestine were the Philistines, the Amorites, the Aramaic city-states, the Canaanite city-states, the states of Israel and Judea, and the Phoenicians.

The Philistines

The immigrants who arrived in Palestine from the Aegean during the twelfth and eleventh centuries BCE became known as the Philistines. Most of them came to southern Palestine by land. Their arrival was not a hostile military-style invasion; rather, they were searching for a new start in a new land. From as early as the beginning of the twelfth century BCE, they established their settlements in five sites in southern Palestine: Ashdod, Ashkelon, Tel Miqne/Ekron, Gaza, and Tell es-Safi/ Gat. This region became known as Philistia, and the settlement system became known as the Pentapolis, the five city-states, the base for a pan-Philistine confederation. The relationship between the Canaanites and the newcomers was characterized by peaceful interaction that led to integration. Archaeological finds suggest that intercultural marriages and intercultural interactions took place, which would have allowed both Canaanite and Aegean traditions to be maintained. 57 Itamar Singer, the history professor at Tel Aviv University, believes that the migrants came without an urban tradition of their own and adopted the Canaanite system of city-states. 58

The migration from the Aegean was not a sudden, single event. It was a prolonged process that started with the gathering of information, followed by the arrival of young men who prepared the ground for the arrival of the rest of the family or larger kinship group. It is believed by most scholars that the first wave of migrants arrived in Palestine at the beginning of the twelfth century BCE. American archeologist William F. Albright interpreted the Medinet Habu records as follows: “The Philistines were first subdued by the Egyptians and then settled in Egyptian forts in Palestine. Later, they managed to break free.” 59 As a result of intermarriages with Syrian women, a substantial number of migrants stayed in Syria for some years before continuing their journey further south into Palestine. The Aegean migration took different forms: some stayed in one site along the route, others continued on; some were joined by other groups of migrants of different origin and by people of non-Aegean origin. A significant number of the immigrants were second- or third-generation Aegeans born in different places along the migration routes, such as Cilicia, Cyprus, and Syria.

The Philistines eventually consolidated their position in the southern coastal plains. A distinctive material culture evolved as a result of the integration of the newcomers with the Canaanites, the indigenous inhabitants of Palestine. The Pentapolis federation of the five Philistine cities produced a local variety of a contemporary style of Mycenaean pottery, which became known as the Philistine style. “This wonderful, artistically inspired pottery combined in a unique painted style motifs derived from Egyptian, Canaanite and Mycenaean traditions. Not only did the Philistines introduce a new and characteristic style of pottery to Canaan, but new styles of architecture [that] strongly reflect the Aegean background and origin of the Philistines themselves.” 60

The Amorites

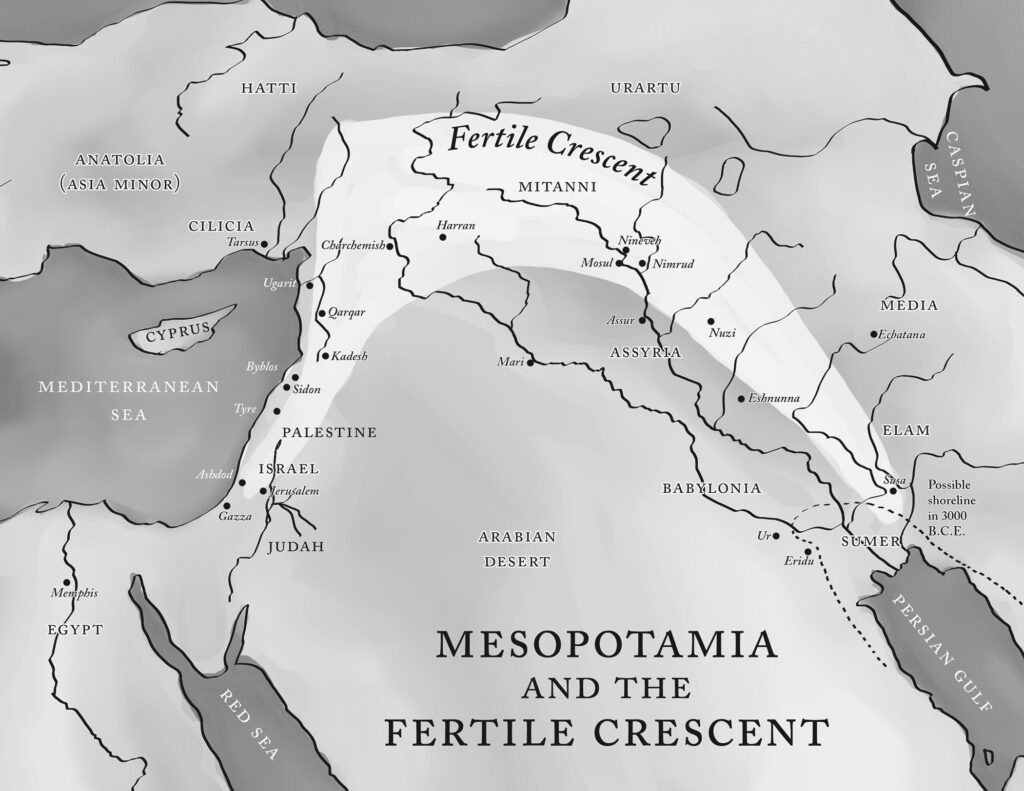

The Amorites are the indigenous population of inland, central, and north Syria, equivalent to the Canaanites of the Levant. The people who occupied Syria during the third millennium were called the Amorites by their eastern neighbors the Sumerians. This word means “westerners,” and their country was known as Amurru, the Westland. Their capital was called Mari, which is also a Sumerian word. Later the Babylonians expanded the name to refer the whole of Syria; they called the Mediterranean “the great sea of Amurru.” The first reference to the land of the Amorites appears as early as the time of the Akkadi emperor Sargon (2450 BCE). Before Sargon of Akkad overran Amurru, its capital, Mari, was the seat of one of the early Sumerian dynasties. 61

The Amorites’ economy was based on an advanced agricultural irrigation system, as well as on commercial relations with their neighbors. From the Gulf of Alexandretta to the western bend of the Euphrates, a distance of approximately 160 kilometers, the land formed a natural corridor between the shores of the Mediterranean and Mesopotamia. The narrow, low passage through the mountains in northern Syria that connected the valley in the east and the sea in the west became known as the Syrian Saddle. This important corridor served as a trade route for exchanging goods as well as a cultural throughway for the exchange of ideas. It was also the main pass that was used by Babylonians, Egyptians, Assyrians, Persians, and Macedonians in their military expeditions.

The name Syria was introduced by the Greeks. In Greek and post-Greek times, the term included Palestine and Lebanon. It described the area between the Taurus and Sinai, the Mediterranean and the Iraq desert. To Herodotus, Palestine was part of Syria, as it was to the Turks (the Ottoman Empire), and its inhabitants were the Syrians of Palestine. The Arabs gave the country a new name: al-Sham (as Syria is still known in Arabic) indicating it was to the left (north), relative to al-Yaman, and to the right (south) relative to al-Hijaz. Geographically, Syria occupies an important strategic position connecting the three continents, which has exposed it to invasions from all sides: from the Babylonians, Assyrians, Egyptians, Hittites, Persians, Macedonians, Romans, Mongols, Turks, Crusaders, and European colonists. Throughout its long history since the Bronze Age, there has hardly been a time in which Syria as a whole stood as an independent sovereign state. 62

At the end of the first half of the twentieth century CE, excavations at a site in northern Syria called Tell al-Hariri (silk merchant’s mound) revealed the ancient site of Mari. The finds included over twenty thousand cuneiform tablets, the language of which is mostly Akkadian, but the vocabulary and grammatical features leave no doubt that those who wrote them spoke Amoritic or West Semitic, which is distinct from East Semitic. The tablets represent the archives of Zimri-Lim (1730–1700 BCE), the last king of Mari, whose kingdom was destroyed by Hammurabi. These records revealed that horse-drawn chariots were already known, and that fire signals were used as a measure of national defense. The language of these tablets indicates that the civilization of the Amorites was a blend of Amoritic, Hurrian, and Babylonian elements. These tablets also reveal that Halabu (Aleppo), Gubla (Jubayl, Byblos), Qatana (Qatna, north of Hims), and Haran were centers of Amorite dynasties or were ruled by Amorite princes. They also indicate that around 1800 BCE, the entire region from the Mediterranean to the highlands of Elam was dominated by Amorite princes. The architecture of the palace of King Zimri-Lim and the documents it contained reveal an advanced culture that rivaled those of Egypt and Mesopotamia.

The ethnic composition of the population of Syria-Palestine is not clear to modern historians. People migrated there from different regions. As mentioned earlier, successive waves of migrants arrived from North Africa as a result of the extensive periods of drought that resulted in the creation of the great Sahara. These waves of immigration arrived between the seventh and fifth millennia BCE. Similar population movements of the Armenoids, the Hurrians, and the Hittites took place from the north and east toward northern and eastern Syria.

The Aramaic City-States

Between the twelfth and tenth centuries BCE, several city-states known as the Aramaean states were established in Syria. The collapse of the Hittite empire at the end of the Bronze Age, along with the withdrawal of Egypt from Palestine-Syria, created a vacuum which was filled by the Aramaic city-states of central and north Syria. Politically there was no centralized authority like a unified kingdom, but it was a formidable confederation of city-states consisting principally of Aleppo, Damascus, and Hamath. This confederation was able to resist and hold the advances of the Assyrian Empire for a relatively long period of time.

Aram Damascus played a major role in the coalition of city-states that confronted the Assyrian forces of Shalmaneser III in 853 BCE. The Aramaean language, Aramaic, was the most widely used language in the entire Near East. It is reasonable to assume that “the Aramaean ‘culture’ [was] a revival and resurgence of the indigenous population. The Aramaeans can be defined then as the population of first millennium (Iron Age) in central and north Syria.” 63

Under Ben-Hadad I, Damascus became the most prominent power in Syria-Palestine. The kingdom of Israel in the central highlands of Palestine (discussed in next section) was a vassal of Damascus during the last days of Omri, the king of Judea, who paid tribute to Ben-Hadad. Gilead in Transjordan was also controlled by Damascus. Aram Damascus was a prosperous community; the Aramaean merchants sent their caravans all over the Fertile Crescent. For centuries they monopolized the internal trade of Syria, while the Canaanites monopolized the maritime trade. Damascus was the port of the desert just as Gubla, Sidon, and Tyre were the ports of the sea. Aramaean merchants were responsible for spreading their West Semitic language throughout the entire Fertile Crescent, and by about 500 BCE, Aramaic had become the dominant language of the Near East. Under Darius the Great (521–486 BCE) it was made the official interprovincial language of the Persian government. With the spread of Aramaic, the Phoenician alphabet, which the Aramaeans were the first to adopt, spread and was passed on to other languages in Asia. 64

The Canaanite City-States

The Canaanites were the indigenous inhabitants of Palestine during the Neolithic period who established major agricultural settlements in the coastal plains, the Jordan Valley, the inland plains, and the inland valleys. They were the inhabitants of the ancient Levant; they had dwelt in that region since the time of the very earliest settled communities in remote prehistory. They were the same people who settled in farming villages in the eighth millennium BCE. 65 It is important to recognize that the Canaanites and Amorites were the indigenous inhabitants of the land since the Neolithic period. Over thousands of years, immigrants from different regions—the west (North Africa), the north (Anatolia), the northwest (Mycenae), the northeast (Armenia and the Caucasus), the east (Mesopotamia and Elam), and the south (Arabia)—slowly and gradually moved into Palestine-Syria, becoming integrated and fully assimilated with the indigenous inhabitants.

The Canaanites were undoubtedly influenced by others through trade and small-scale immigration. Nonetheless, the Ammonites, Moabites, Israelites, and Phoenicians who achieved their own cultural identities could all be classified as different parts of the multicultural entity that comprised the Canaanites. These groups are often described as distinct kingdoms, but in fact they were interconnected and interdependent. As described in the previous chapter, the Canaanites rose through the stress of the great Mediterranean drought, which forced different cultural groups to cooperate in the Mediterranean economy. Whereas some civilizations were weakened or devastated by the drought, the Canaanites were strengthened by it, because they had to become interdependent based on the different economic specialties of each region. This drove advancements in language, technology, and trade that shaped the culture of the region.

The land of Canaan, which means “lowland,” is defined geographically as the ancient Levant, which includes the modern areas of Palestine, Transjordan, coastal Syria (including Lebanon), and southern inland Syria. The Canaanites were the indigenous inhabitants who, during the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods, built Megiddo, Beth Shan, and Acco in the northern lowlands; Ashqelon and Gaza in the southern lowlands; and Hazor (Tel al-Qadeh), Shechem, Jerusalem, Lachish, and Gezer in the highlands. The continuity of population in the Levant from the beginning of settled communities in the Neolithic period through the Chalcolithic, Bronze, and Iron ages cannot be challenged.

By the eleventh century BCE, as the great Mycenean drought came to an end, Palestine slowly began the process of rebuilding its economy and reviving its society. All the agricultural regions—Phoenicia in the north coastal region; Philistia in the southern coastal plains; Samaria in the central highlands; and Ammon, Moab, and Edom east of the Jordan rift and in the Transjordan Plateau—prospered in the tenth century BCE.

As previously noted, during the long drought years, Egypt had maintained a significant military presence in Palestine, which played a major role in overcoming the serious problems created by the extended drought. At the end of the eleventh century BCE, due to internal discord, Egypt withdrew from Palestine and ended its control and hegemony.

Palestine-Syria became independent, but fragmented, with dominant towns starting to control the small villages in the immediate neighborhood. The majority of Palestine’s sedentary population lived in the Jezreel Valley and the connecting Beth Shan and northern Jordan valleys. The Iron Age witnessed the city-state system, in which major cities established their independent states, known historically as the world of the Canaanite city-states. This period was characterized by instability, as no single city-state was able to dominate the scene. “This endemic fragmentation into its many small regions left Palestine not only torn by recurrent regional conflicts, but extremely vulnerable to the armies of major powers from outside Palestine.” The independence of the city-states lasted for a full century, ending around 900 BCE with the rise of the Assyrian Empire. 66

The city-states continued their commercial activities with both Egypt and Mesopotamia and tried to maintain trade routes; however, the relationship between these states was dominated by competition rather than cooperation. The Assyrians benefited from this situation, and moved to fill the vacuum created by the withdrawal of Egypt from Palestine-Syria. There followed an increase in the volume of international trade between Egypt and Assyria. The trade route that passed through the Jezreel Valley connected the coastal plains to the upper Jordan Valley. No single power was able to control this route and maintain security and stability. The Phoenician city of Tyre competed with Damascus for control of the valleys and the trade routes. The small mountain villages of western Galilee were allied with Tyre, while eastern Galilee was controlled by Damascus. As the people of the central hills consolidated and created the state of Israel, a three-way struggle for dominance over Jezreel developed. For more than a century, the relationship between the three states of Tyre, Samaria, and Damascus was characterized by attempts to cooperate at some times, and periods of war at others. 67

The southern highlands, which became known in the seventh century BCE as Judea, lacked a centralized political structure. However, the scene in this region was dominated by small autonomous towns, including Jerusalem and Hebron in the hill country and Gezer and Lachish in the Shephelah (lowlands).

The City-States of Israel and Judea (1300–600 BCE)

In Palestine, the highlanders in both the central hills (later Samaria) and southern hills (later Judea and Jerusalem) came from people displaced from the lowlands. They were part of the indigenous population of Palestine who were displaced from their towns and villages as a result of the great Mycenean drought. The settlements of these highlands evolved into two states: the first state, which became known as Israel, was in the central hills, and its capital was Samaria; the second state, which became known as Judea, was in the south, and its capital was Jerusalem. Israel was founded in the tenth century, while the state of Judea, lagging behind Israel by three centuries, was founded in the seventh century. Their beliefs, religious practices, political system, culture, and social life were similar to those of the other communities of the southern Levant and Greater Syria.

Prior to the great drought, the majority of Palestine’s population lived in the central valleys and the coastal plains, where major towns were located. During the thirteenth century BCE, in response to the drought, farmers moved out of the major towns toward more remote and isolated areas of the lowlands, establishing new villages along the northern coastal plains around Acco. More small villages were also established in the Jezreel, Beth Shan, and northern Jordan valleys. As the number of refugees increased in these regions of the lowlands, they began moving into the central highlands north of Jerusalem (later Samaria). Initially they settled in the fertile interior valleys where there were small streams and springs. Later on, they established new settlements beyond the valleys into high grounds where they could grow grains and where herding would be possible. Even in periods of drought, highland rains were sufficient to maintain some form of dry agriculture. The new settlers developed the central hills into rich agricultural land suitable for olive trees, vineyards, and fruit orchards. They built terraces and adopted different methods for the maintenance of the limited water resources. They used slaked-lime plaster for the lining of the water cisterns and constructed large clay-jar containers for both water and grain storage. 68

The collapse of sea trade with Hatti, north Syria, and Phoenicia caused Egypt to lose its timber and oil suppliers. Egypt looked to Palestine as a potential new supplier of these products, so it expanded its presence there. Its willingness to pay inflated prices for both timber and oil encouraged entrepreneurs to move to the highlands and to establish new settlements. Egypt also helped integrate the Aegean refugees with the indigenous population and provided security and political stability to the region. These measures resulted in a significant population increase in the central hills. The population of this region responded to the growing market, building a diverse economy dependent on a variety of products, including oil, wine, fruits, nuts, and grain, to meet Egypt’s needs. The timber industry cleared the forest lands and turned the wilderness into the richest olive-producing area of Palestine. 69

Judea and Jerusalem

The southern hills, which are known as the Judean highlands, were dominated throughout the drought by pastoral nomads. Except for few small, scattered hamlets, sedentary life was absent. The dryness during this period prevented any agricultural activity. Lachish, which was located southwest of the hills, dominated the region, as it functioned as the central market that connected the highlands with the overland trade routes. Meat, cheese, butter, and wool reached the trade routes through Lachish. When the drought ended around 1050 BCE, the Judean highlands became able to support agricultural settlements. Lachish took the initiative and encouraged the nomads to convert the grazing lands into farming communities. By the end of the ninth century BCE, most of the Judean highlands had been cleared and terraced, and the region became one of the most important olive-growing areas of Palestine. In Judea, the greatest expansion of settlements occurred between 900 and 700 BCE, lagging behind the central hills by two centuries. During this period, Jerusalem was a very small town, and did not play any significant political role in the region.

Only after Lachish was destroyed by the Assyrians in 701 BCE did Jerusalem develop and grow to become the economic and political center of the south. 70

The northern highlands in the upper Galilee region had a different history. This region received more rainfall than any other region of Palestine; however, it was rugged and heavily wooded. Agriculture was more difficult in these hills, so settlements were fewer and widely scattered. During the Mycenaean drought, refugees settled in small farming villages in the northern hills. They were involved in grazing and grain agriculture, as well as cultivating olives and fruits. The western part of the northern highlands was connected with the Phoenician ports in the northern coastal region, while the eastern part was connected with the towns and villages located near the Sea of Galilee and the Hula basin.

The Origins of the City-state of Israel

Archaeological finds and historical records clearly indicate that the state of Israel in the central hills was developed on its own and was not an offshoot of a glorious “united monarchy” of the south. The population of the highland settlements in both the central and the southern hills in the tenth century was approximately 45,000 people. Ninety percent of the population inhabited the villages of the central hills north of Jerusalem. About five thousand people lived in the southern hills, scattered among Jerusalem, Hebron, and some twenty small villages. 71 Such a small, isolated society was unlikely to support a great empire or host a great capital. There were simply not enough people in the south hills to establish such a kingdom. There is no evidence of the presence of any political force anywhere in Palestine that could establish such a state. 72

The development of the southern highlands into a state started around 1050 BCE, when sedentarization began and the nomads established their agricultural communities. It took the settlers three centuries to be able to build the state of Judea; around 700 BCE the region was organized in the form of a state with Jerusalem as the capital. The Iron Age town of Jerusalem that was excavated by Kathleen Kenyon in the 1960s offered no significant remains from the late Bronze Age; the earliest structures discovered went back to the tenth century BCE. Thus, the history of Jerusalem began with the Iron II period. After the fall of Lachish in 701 BCE, Jerusalem’s power and influence extended southward over the Judean highlands. By the mid-seventh century, it had become a city of over 25,000 people, and was the capital of the Assyrian client state of Judea. 73

The biblical stories present a golden age of an ancient state of Israel with its capital in Jerusalem. This state, called the “united monarchy,” was supposedly established by Saul, and reached its peak during the period in which King David and his son Solomon controlled a huge territory from the Nile to the Euphrates. These stories also talk about a temple built by Solomon as the center of the worship of Yahweh.

According to the archaeological record, this storied kingdom does not exist in the actual historical past. Historian and archaeologist Thomas Thompson, who studied this era of the ancient history of Palestine, concludes:

There is no evidence of a united monarchy, no evidence of a capital in Jerusalem or of any coherent, unified political force that dominated western Palestine, let alone an empire of the size the legends describe. We do not have evidence for the existence of kings named Saul, David or Solomon; nor do we have evidence for any temple at Jerusalem in this early period. . . . There is . . . no artifact or archive that points to such historical realities in Palestine’s tenth century. One cannot speak historically of a state without a population. Nor can one speak of a capital without a town. Stories are not enough. 74

Historically, there was a small state called Israel (Samaria) in the central hills of Palestine in the early ninth century BCE. This small state started as a collection of villages and hamlets established by the displaced populations from the lowlands. The settlements had started at the beginning of the thirteenth century BCE; it took more than three centuries for the region to become organized in the form of a state. The settlers worked hard to turn the wilderness into the richest olive-producing area of Palestine. They were dependent on trade and barter with each other for survival, with an economy based on cash crops grown primarily for market. Olives became Palestine’s principal export. With the opening of international trade in the tenth and ninth centuries, sending goods to market required cooperation among the villages in the region, which led to the creation of a centralized administration and other forms of statehood, including dynastic kingship. The kingship developed from traditional forms of patronage and centered on the great families of the area. In the earliest records available that refer to this small state, one of the first families to control the central highlands was the house of Omri. Omri was a prominent local leader who played a significant role in creating a central authority in this region, which developed into a Canaanite city-state. The international trade route crossed through the Jezreel Valley just north of the highlands. Because its existence depended on international trade, it was destined to become a vassal state of the great empire of Egypt or the great empire of Assyria.

Religion played a major role in the new city-states of Palestine in the late Bronze and Iron ages. The religion in these states did not differ in form or content from religious practices throughout Syria. In all the Near East, people believed in the concept of a pantheon of gods. El was the father of the gods and the creator of heaven and earth. The human king was considered the representative of a god; he was not the patron himself, but the servant of the god, the executor of divine patronage. 75 The state of the central highlands became known historically as Israel. The word “Israel” is composed of two syllables: Isr and El. This name, which was given to the state by its leader Omri, meant “El will rule.” 76 The myth in the Old Testament claims that Yahweh, who fought with Jacob, gave him the name Israel, which means “the one who defeated God.” Initially Shechem (now Nablus) was the most dominant city in the region, but Omri’s dynasty later built Samaria as their capital.

The Phoenicians

Phoenicia is the northern part of the land of Canaan along the eastern shores of the Mediterranean. The name originates from the Greek word phoinix, which means “red-purple” and refers to the people of that region who extracted a special colorful dye from tiny sea creatures similar to snails. The term Phoenicians was first applied by the Greeks to the Canaanites with whom they traded. After 1200 BCE, the term “Phoenicians” became synonymous with Canaanites (as noted above, the Canaanites were an interconnected, interdependent group of city-states linked by the Mediterranean economy).

The coastal plains along the eastern shores of the Mediterranean run from the Sinai in the south to the Gulf of Alexandretta (Iskandarunah) in the north. Between the sea in the west and the mountains in the east, the plain widens in the north and in the south. At Juniyah, north of Beirut, it is just one mile wide. About five kilometers south, at the mouth of Nahr al-kalb, the mountain touches the sea. At Carmel, the plain is just two hundred yards wide. There are two chains of mountains: the Lebanon Mountains (whose highest peak is 3,090 meters) and the Anti-Lebanon Mountains (highest peak 2804 meters) with the fifteen-kilometer-wide Bekaa Valley in between. The Lebanon Mountain chain contains many rivers that flow westward to the sea: the Litany and Orontes rivers provide water to the rich agricultural land of the Bekaa Valley.

Sedentary life was established in Phoenicia as early as the beginning of the Neolithic Age. Byblos was among the first Palestinian settlements of that period. During the early Bronze Age, the Phoenician ports were the most prosperous cities in Palestine. The main cities were Byblos, Tyre, Sidon, Berytus, and Arwad. The Mari archives refer to diplomatic and commercial relations between Egypt and Syria-Palestine during the reign of the pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom. The Egyptians were interested in raw products and luxury goods from the Aegean region and the east, through the commercial centers of Syria and Palestine.

As early as 2900 BCE, the Phoenicians were involved in sea trade and exploration. Their earliest international routes connected Byblos with Egypt. Over time these routes expanded to include the entire Mediterranean. Their trade activities reached a peak around 1000 BCE, by which time they had established several colonies around the Mediterranean and beyond. They supplied timber, wheat, oil, and wine to several Mediterranean countries. Cedar wood was an important commodity; both Egypt and Mesopotamia used it to construct temples and palaces as well as fishing boats, merchant ships, and naval vessels. Gradually the Phoenicians became the distributing agents between west and east, practically turning the Mediterranean into a Phoenician lake.

At first, the Phoenician sailors kept the coast in sight and only traveled by day. Driven by their desire to expand their trade, they discovered the usefulness of the North Star (later called the “Phoenician Star”), which enabled them to navigate at night and master the art of night sailing. Gradually they developed shipbuilding techniques that allowed them to carry large cargos. They placed two or more rowers one above the other to gain more power and speed. In later times, the number of rowers reached fifty.

The Phoenicians were the first to sail around Africa—two thousand years before the Portuguese. Pharaoh Necho (609–593 BCE) of Egypt’s twenty-sixth dynasty reopened the ancient canal connecting the eastern arm of the Nile with the head of the Red Sea. The Phoenician vessels sailed through this sea toward the southern ocean. During the autumn they would land wherever they arrived, plant wheat, await the crop, and then depart the following year. At the end of their two-year journey, they returned to Egypt through the Pillars of Hercules (modern-day Gibraltar).

The Phoenicians established several colonies throughout the Mediterranean. One trading post after another developed into a settlement, and one settlement after another into a colony, until these colonies were linked together and to the mother cities. The settlements in the mid-Mediterranean isles go back to the middle of the eleventh century. Gades in Spain and Utica in Tunis were founded about 1000 BCE. The founding of Gades beyond the Strait of Gibraltar introduced the Phoenicians to the Atlantic Ocean and resulted in the discovery of the ocean by the ancient world. This is considered among the greatest contributions of Palestinian-Syrian civilization to world progress. In search of tin, they reached Cornwall in England. The Phoenician ships carried not only cargos of different materials and products, but also ideas. Phoenician merchants and colonists influenced those whom they came in contact with in more important ways than exchanging products. They introduced culture which enhanced the civilization of the world around them. The Greeks were the ones who benefited the most from contact with the Phoenicians: they learned navigation and colonization, as well as literature, religion, and art. Through the Phoenicians, the Mediterranean became the base of cultural exchange between the Canaanites, the Babylonians, the Egyptians, and the Greeks. They were the middleman intellectually and spiritually, as they were commercially. 77

One of the most significant contributions of the Phoenicians to civilization was the introduction of the alphabet. The invention and dissemination of the alphabet system is considered their greatest gift to humanity. They were familiar with the Sumerian cuneiform method of writing as well as the Egyptian hieroglyphic method.

They adapted these forms of writing and developed a new system based on the principle of representing the sounds of the voice in the form of letters. The simplicity of the Phoenician alphabet system, with its twenty-two letters written from right to left, brought the art of writing and reading within the reach of the ordinary man.

The Phoenician cities were under the influence and control of Egypt during the reign of the pharaohs of the Old and Middle Kingdoms. This control was loose, being limited to paying tributes to Egypt and securing international trade routes. During the rule of the New Kingdom, from around 1600 BCE until about 1050 BCE, the entirety of Palestine became part of the Egyptian empire. The Phoenician cities played an extremely important role in international trade between 1600 and 1300 BCE, before the Mycenaean drought, connecting Egypt with the Aegean region and the Mediterranean isles. Between the eleventh and the tenth centuries, when Egypt started withdrawing from its Asiatic territories, the Phoenician cities, like the rest of the Palestinian cities, became independent, and were part of the Canaanite city-state system. The tenth century was the beginning of the golden age of the Phoenicians, in which they began establishing their colonies throughout the Mediterranean.

Tyre—the name means “rock”—was one of the most famous Phoenician cities. Founded around 2750 BCE, it consisted of two parts: the main trade center, which was on an island, and “old Tyre,” about a half mile away on the mainland. The people of Tyre founded several colonies around the Mediterranean. The most prominent of these was the ancient city of Carthage (now in Tunis), in North Africa, which was founded around 850 BCE in a location that allowed for control of trade from the eastern to the western Mediterranean Sea. Carthage reached its peak in the sixth century BCE, when it became a mighty empire extending from Cyrenaica (modern Libya) to the Pillar of Hercules (Gibraltar), encompassing the Balearic Islands, Malta, Sardinia, and several settlements on the coast of Spain and Gaul (France). This expansion brought Carthage into conflict with Rome, “who contested with her the supremacy of the sea, on which the Carthaginian fleet had such a hold that the Romans were told they could not even wash their hands in its waters without Carthage’s permission.” 78

In summary, the history of ancient Palestine from the Bronze Age through the Iron Age was influenced by multiple overlapping and competing civilizations. All of them were greatly affected by the great Mycenean drought. This affected the distribution of population centers and gave rise to a loose confederation of city-states, including Israel and Judea, among others. The Phoenicians, as an extension of the Canaanites, were the dominant disseminators of early Palestinian-Syrian culture, language, writing and trade throughout the Mediterranean.