The concept of a Palestinian national identity grew out of the Arab uprising. It was strengthened by the British occupation and the growth of a Zionist presence in the land.

Palestinian Influence in the Arab Revolt

During the Ottoman rule of Palestine, the notables of the urban elite (A’yan) played a major role in the Ottoman administration. They were members of the governor’s council, which provided them formal access to Ottoman power. On their own, they possessed social power in their communities that afforded them access to the ruling authority; this access enhanced their local social position. They took care not to be perceived as an instrument of the central authority, and at the same time were careful not challenge the authority too strongly to avoid the risk of being deprived of the access to the ruler. They were the intermediaries between the government and the Palestinian population. As a result, the notables defended the social order and were loyal to the Ottoman authority. Political stability helped them preserve their positions of influence and power. The Ottomans derived their legitimacy in the eyes of Muslims through the control of the holy cities. During the reign of Sultan Abd al-Hamid, notable families began to send their sons to Ottoman professional schools from which they entered the civil or military service. Joining the Ottoman “aristocracy of service” enhanced their power.

Although the Ottoman reforms of the second half of the nineteenth century (the Tanzimat) succeeded in strengthening the power of the government in Cairo and Istanbul, they did not work in the outlying provinces like Palestine; on the contrary, the governors needed the notables more than ever because of the opposition which the new policies elicited.

The Young Turks’ CUP coup was a turning point in the position of the notables. The Young Turks dismissed many of the notables from their positions in the central government in Istanbul and began the Turkification of the empire. Many of the notables shifted from Ottomanism to Arabism; however, until the outbreak of World War I in 1914, they stressed only the need for reforms within the Ottoman Empire through Arab autonomy and not through secession.

Throughout the war, most of the Palestinian notables took the Ottoman side. When the Ottoman Empire entered the war on the side of Germany, many dominant Palestinian notables supported the sultan. Even Jamal Pasha’s anti-Arab policy and the Arab revolt of 1916 did not change their position. A large number of Arab leaders maintained their loyalty to the Ottoman state despite Jamal’s actions. On the contrary, some passed information on the Arab activists in Syria to the Ottoman authorities. As’ad al-Shuqayri was one of the first to report to Jamal Pasha about the revolt that was being planned by Arab nationalists in Syria. The execution, exile, and imprisonment of young Arab nationalists prevented them from making any significant contribution to the Hashemite’s revolt.

Palestinian participation in the Arab nationalist societies was significant. Out of the 126 members of the secret societies, a total of twenty-five were Palestinians: thirteen were from Nablus, eight from Jerusalem, one each from Jaffa and Haifa, and two from Gaza. Of the 387 names who sent telegrams in support of the Arab congress held in Paris in June 1913, a total of 139 were Palestinians: forty-four from Nablus and its environs (Nablus was considered the Beirut and Damascus of Palestine). Several Palestinians played a major role in the organization of the Paris congress.

On the eve of the fall of Palestine in the autumn of 1918, political control was in the hands of the older notables. The disintegration of the Ottoman Empire meant for these notables that Ottomanism was no longer a viable political ideology, so they turned toward Arab nationalism to protect their position of strength in local society. The younger Syrians, Palestinians, and Iraqis, who had either been officers in Faysal’s army during the war or members of the secret societies, became the real masters of Faysal’s regime.

As the British took control of Palestine, the older notables turned toward the new master and were ready to accept posts in the new administration. They were not ready to accept Zionism, but they were ready to cooperate with the British. They elected to present petitions against Zionism and the British Zionist policy to the British authority in Palestine. The British military administrators were unenthusiastic about the British Zionist policy in Palestine. As stated earlier, the three chief administrators during the military administration—General Money, Major General Watson, and Major General Bols—warned their government that the Palestinian Arabs were vehemently opposed to Zionism, and that the Zionist program would result in serious conflict between the Arabs and the Jews. The response from London was very clear: the British colonial strategy was a solid one; the imperial plans of Britain in the Far and the Middle East would not change; and Britain was determined to create not just a national home for the Jews in Palestine, but a Zionist state.

The Arab nationalists from Palestine viewed Faysal’s government in Damascus not just as the fulfillment of the dream of Arab independence, but more importantly a great source of strength in their struggle against Zionism. Tens of Palestinians played an active role in Faysal’s administration. The most prominent members of this group were Muhammad Izzat Darwaza, Rafiq alTamimi, and Awni Abd al Hadi. Izzat occupied several political positions—secretary of al-Fatat, secretary of the Nablus Muslim-Christian Association; secretary of the First Palestinian Arab Congress, which convened in Jerusalem in January 1919; secretary of the General Syrian Congress; and member of the leadership of al-Istiqlal party. Rafiq alTamimi, who attended al-Mulkiyya school in Istanbul, was awarded a grant by the Ottoman Ministry of Education to study at the Sorbonne in Paris. Awni Abd alHadi, who also attended al-Mulkiyya school in Istanbul, received a law degree in Paris. The Palestinian group focused most of their attention on the affairs of Palestine. They founded several political organizations in Damascus aimed at rallying support for the struggle against Zionism: Jam’iyat alNahda alFilastiniyya (the Palestinian Renaissance Society), alJam’iyya alArabiyya alfilistiniyya (The Palestinian Arab Society) and Jam’iyyat Fatat Filastin (The Palestine Youth Society). The primary Palestinian organization in Damascus was alNadi alArabi (The Arab Club); its main function was to promote the idea of pan-Syrian unity and to convince Faysal to reject any cooperation with the Zionists. 287

Spreading Political Ideology

During the British rule of Palestine, the freedom and power held by the notables during Ottoman rule was lost despite the fact that they continued to be accepted by the Palestinian Arabs. During this period, more than forty Arab political associations emerged with a total of more than three thousand members. These associations can be classified into two groups: First was the older politicians, who belonged to the families whose members had been officers or civil servants in the Ottoman Empire; the second was the younger politicians, most of whom also came from influential aristocratic families, but had not been part of the Ottoman imperial bureaucracy. 288

The older Palestinian politicians were represented by the MuslimChristian Association. Most of the MCA notables came from the same class, and the same interests influenced their attitudes and behavior. They maintained their old tradition of access to authority. They were cautious in expressing their discontent with the British policy. The British, like the Ottomans, needed intermediaries between the mandate authority and the Palestinian population, so the British military officers encouraged the establishment of the MCA. Years after the fact, Sir Wyndham Deeds (chief secretary of the Palestine government during the mandate period from 1920 to 1923) claimed to the head of the Arab Department of the Zionist Executive, Hayyim Kalvarisky, that the MCA received financial aid from the Palestine government. 289

The MCA was merely a loose alliance of notables designed to penetrate society and incorporate new social forces. In the First Palestinian Congress in February 1919, the MCA declared its strong opposition to the Jewish national home and to Jewish Immigration, and stated that it considered Palestine part of Arab Syria. Its objectives were defined as the preservation of the material and moral rights of the Palestinian people; the advancement of the agricultural, industrial, economic, and commercial conditions of the homeland; the revival of learning; and the edu cation of the new “nationalist generation.” 290

The second group—the younger Palestinian politicians—founded two organizations: alMuntada alArabi (the Literary Club) and alNadi alArabi (The Arab Club). AlMuntada was originally founded in Constantinople in the summer of 1909 by Abd al-Karim al-Khalil of Tyre, Lebanon, and by a group of officials, deputies, men of letters, and students to act as a meeting place for Arab visitors and residents in the Ottoman capital. This club had branches in several towns in Syria and Iraq; its membership ran into the thousands. Jamil alHusayni of Jerusalem was one of its most active members. In November 1918, the club reemerged in Jerusalem with a new political program. The club was largely dominated by prominent members of the alNashashibi family who did not belong to the Ottoman aristocracy of service. The club demanded complete Arab independence and the union of Palestine with Syria. Its active members worked diligently to rally support for Faysal in Palestine throughout 1919 and early 1920. Jerusalem was the center of the club, with several branches in other towns of Palestine.

AlNadi alArabi was founded by the younger members of al-Husayni family. Muhammad Amin alHusayni was one of the prominent leaders of the club. The club was originally set up by Palestinian Arab Nationalists in Damascus as an offshoot of al-Fatat. The Damascus central organization of the club was dominated by Arab nationalists from Nablus. On behalf of the central committee of al-Fatat and al-Nadi al-Arabi in Damascus, Dr. Hafiz Kanaan of Nablus maintained contact with the Arab Club in Jerusalem. Muhammad Amin al-Husayni, in his capacity as the president of the club in Jerusalem, met frequently with Kanaan in Nablus and agreed to work within the framework of the instructions of Faysal’s administration in Damascus.

Through al-Fatat, Kanaan also rendered financial assistance to the Jerusalem branch of the club. Members of al-Nadi al-Arabi cooperated with al-Muntada in promoting the idea of pan-Syrian unity in Palestine. The two clubs arranged for a joint appearance before the King-Crane Commission in the summer of 1919, and submitted joint petitions demanding unity with Syria to the British military authorities in Palestine.

In Palestine, al-Nadi al-Arabi spread its ideas through mosques, the press, and active mobilization in several Palestine towns and villages. The newspaper Suryia al-Janubiyya (Southern Syria) was founded in Jerusalem in September 1919 and edited by two members of the club, Muhammad Hasan al-Budayri and Arif al-Arif. The president of the club, Muhammad Amin, campaigned among the Palestinian Arab peasants and city dwellers propagating anti-Zionism and unity with Syria and Palestine. He played a significant role in the demonstrations of the Muslim al-Nabi Musa of April 1920. The club devoted efforts to establishing schools and medical clinics for the poor, and delivered speeches about social and literary topics.

These two clubs were behind the establishment of a secret organization, Jami’yyat alIkha’ walAfaf (the Association of Brotherhood and Purity), whose membership did not exceed two hundred. Set up to carry out violent actions, it lasted for less than a year. Associated with this organization, another society, alFida’iyya (Self-Sacrificer), was established initially in Jaffa in early 1919 and lasted until 1923. Branches of this organization were established in Jerusalem, Gaza, Tulkarm, Lydda, Ramla, Nablus, and Hebron. It was in close contact with Damascus. Every member took the oath upon enlistment that a traitor should be killed by his own friend. According to Zionist and British source material, these organizations were providing their members with small arms, preparing a list of prominent Zionists and their collaborators, and contacting the Bedouins of Transjordan to gain support. 291

Jerusalem, the most important city in Palestine, derived its importance from being the Holy City. The notables of Jerusalem were the most influential in Palestine. The main notable families of Jerusalem were the Husaynis, the Nashashibis, the Khalidis, the Alamis, and the Jarallas. The Husaynis and the Nashashibis dominated the political scene in Palestine through the entire mandate era. Their political ideology was initially the same with minor differences: both chose to cooperate with the mandate government, justifying this conduct as being the most effective strategy to achieve nationalist goals.

The older notables, including the Husaynis and the Nashashibis, had almost the same ideology in regard to their opposition to Zionism, the Balfour Declaration, and the British mandate. They advocated nonviolent means in their opposition to the Zionist policy of the mandate government. They were almost in a state of denial regarding the real strategic goals of Great Britain’s plans to establish a Jewish state in Palestine. The main motive of the Balfour Declaration was “the protection of British imperial interests in India, the Persian Gulf, and the Suez Canal.” Even those who acknowledged Britain’s true goals continued to believe that the right action was to try to change the British strategy. Some of them certainly collaborated with the British and even with the Zionists.

The relationship of the mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin al-Husayni, with the British was completely a different arrangement. From the start, he signed an agreement with Herbert Samuel that he would use his position as the mufti of Jerusalem and the president of the Supreme Muslim Council to maintain peace and to prevent violence. He stood strong behind his promise and fulfilled his duty as an employee of the British mandate government.

Between 1923 and 1928, the Palestinian Arab nationalist movement was in state of stagnation due to the disunity between the different factions of the notables (mainly the conflict between the two families, the Husaynis and the Nashashibis). In November 1923, the Nashashibis founded what they claimed to be the moder ate Palestine Arab National Party. Its leading figure was the mayor of Jerusalem, Ragheb Bey Nashashibi, and its permanent characteristic policy was opposition and hostility toward the Husayni family. Its program that was presented to the public featured an Arab Palestine, a representative government, and an end to Zionism. But in fact, the party was prepared to accept the reality of British mandatory rule. Although it was verbally hostile to Zionism (in public), the party enjoyed covert financial support from the Palestine Zionist Executive. Moreover, of those Palestinians who sold land to Jews, the majority were members of the Palestine Arab National Party. 292

This party was able to broaden its presence in the country by building a coalition of notables opposed to the Palestine Executive and to the Supreme Muslim Council. They gained the support of Sheikh Suleiman Taji al-Faruqi of Ramleh, Sheikh As’ad Shuqayri of Acre, and several wealthy westernized Muslims. They also were able to get the support of prominent Christians such as the editors of the two leading independent Arabic newspapers in Palestine, Filastin and al-Karmel, which both came to support the new party.

In 1926, Hajj Amin faced a setback at the Supreme Muslim Council when the High Court annulled its elections because of irregularities. The mandate government intervened and saved the day for Hajj Amin by appointing new members from among his supporters. In 1927, Hajj Amin faced another setback when his opponents scored a convincing victory in municipal elections all over the country. From 1924 onward, the Palestinian Executive lost a significant degree of influence in Palestine’s politics, which was reflected during the meeting of the Seventh Palestine Arab Congress in Jerusalem in 1928. This loss was obvious in the moderation of its resolutions and in the composition of the newly elected executive committee. However, Hajj Amin was able to regain his strong position as the most prominent Muslim leader in Palestine during the events of August 1929 (the Western Wall riots).

The 1929 Palestinian Uprising

In the seventh century, long after the Temple of Jerusalem had been destroyed by the Romans (see page XX), the entire temple compound, including the Western Wall, became the property of a Muslim trust (waqf). Most of Jerusalem’s Jews were not Zionists; their presence in the city was of a religious nature. They used to practice some of their religious traditions at the Wall. In 1918, the Zionist leaders began trying to buy the Wall area from the waqf. The Muslim officials of the waqf rejected the offer, feeling that the Zionists were trying to acquire the waqf holdings as a part of their plans to construct a Jewish building within the holy Muslim compound. The Muslims’ fears prompted the waqf officials to begin constructing a building within the compound overlooking the Wall. The Zionist leaders appealed to the mandatory authority to stop the work, complaining about the noise and the structural changes to the site. The construction work stopped temporarily and then was resumed in July 1928. Jabotinsky’s followers organized a protest on August 14, 1928, expanding their activities and bringing many objects to the site. The following day, the Muslims called for a counter-demonstration at the Wall, at which the Jewish religious objects that had been brought by the worshipers to the site were burned. The next week rumors were circulated among the Palestinians that the Zionists intended to destroy the principal Muslim shrine (al–Aqsa). In response to these rumors, the Muslims attacked the Jewish quarter in Jerusalem. Over the next five days, the attacks grew in intensity and spread throughout the country, resulting in the deaths of 133 Jews and 116 Arabs.

The British government dispatched an investigating commission headed by Sir Walter Shaw in order to determine the cause of the violence. The Shaw Commission’s March 1930 report concluded that Zionist land purchases had created a “land less and discontented class” within the Arab peasantry. The Commission defined Britain’s principal task in Palestine as holding the balance between the two communities, and urged the mandate government to restate its policy so as to remove any impression of favoritism toward Jews. 293

The government in London stopped issuing immigration certificates to Jews, and commissioned an economic adviser, Sir John Hope-Simpson, to examine the questions of immigration, land settlement, and development. In October 1930, HopeSimpson interviewed representatives of 104 Arab villages and found that 30 percent of Arab cultivators had been deprived of their livelihood from agricul ture. Substantial growth of the Palestinian Arab population during the decade combined with increased land sales to the Jews had created landless Palestinians. HopeSimpson described the situation in the rural areas: “Evidence from every pos sible source tends to support the conclusion that the Arab fellah [peasant] cul tivator was in a desperate position. He has no capital for his farm. He is, on the contrary, heavily in debt, he has to pay very heavy taxes, and the rate of interest on his loans is incredibly high.” 294

Hope-Simpson concluded his report with a number of specific and general policy proposals. For immediate relief, he recommended ending imprisonment for debt, exemption from taxation for lowincome peasants, credit and education for peas antry; and for the longer term, extensive agricultural development programs. He strongly argued, as did the Shaw Commission, for regulation of land transfer and tight restrictions on immigration. He recommended that the policy of the mandate government in regard to Jewish immigration must be determined by unemploy ment in Palestine overall, not just in the Jewish community. He acknowledged, “It is wrong that a Jew from Poland, Lithuania, or the Yemen should be admitted to fill an existing vacancy, while in Palestine there are already workmen capable of filling that vacancy, who are unable to find employment.” 295 The colonial secretary, Lord Sidney Webb Passfield, issued a document which became known as Passfield White Paper, based on the recommendations of HopeSimpson and the Shaw Commission. In addition, the Passfield White Paper proposed that it was time to develop institutions for selfrule in Palestine. 296

The Passfield White Paper came under vigorous attack by the Zionists and pro-Zionists in Britain and Palestine, which overwhelmed the minority government of Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald and prompted him to reverse the policy changes suggested in the Passfield White Paper. This policy reversal, expressed in a clarification in front of the British House of Commons and in a communication sent to Weizmann (labeled the “black letter” by Palestinians), kept in place the very social, economic, and institutional processes that the British authorities had determined to be the causes of the disturbances in Palestine. These processes picked up momen tum in the first five years of the 1930s and led to the greater Palestinian revolt of 1936, which stood not only against the Jewish settlers but also directly against British rule.

Meanwhile, Mufti Amin al-Husayni transformed the religious conflict into a political one. His position as the president of the Supreme Muslim Council, being responsible for all waqf property, including the Western Wall, prompted him to defend the Muslims’ claim. The mufti believed that the influence of the Zionists in London and United States, which became more obvious after the establishment of the Jewish Agency in 1929, could lead to the loss of Muslim control over this important waqf property. In November of 1929, he developed a new strategy aimed at publicizing the issue among the Palestinians and the Arab and Muslim worlds in order to unite them behind this issue and use their collective power to influence British policy.

The mufti claimed that he had fought both the British and the Zionists during the Western Wall controversy because he realized that the British were supporting the Zionist claims. Almost all his statements and actions, from September 23, 1928 until September 1929, indicate that he cooperated with the British during this critical period. When he was asked to suspend renovations at the Wall until the law officers of the Crown reached a decision about the legality of the action, he agreed. He promised the high commissioner to help maintain order, as he believed in Britain’s tradition of justice.

The events of 1929 in Palestine were the turning point in the history of the Palestinian resistance. Until then, the leadership of the Palestinian National Movement had been in the hands of the traditional notables who cooperated with the British and advocated nonviolence, limiting their activities to petitions or sending delegations to London. They were interested in protecting their privileges that they earned from the British in return for good behavior. Many of them were employed by the British administration. Hajj Amin, as the mufti of Jerusalem, was an employee who served the high commissioner.

The Palestine Arab Executive adopted a policy of cooperation with the British from the outset. The president of the executive, Amin al-Husayni, continued to cooperate with the British in spite of significant opposition and rejection by the Palestinian masses, even after British prime minister Ramsay MacDonald had reversed course on the Passfield White Paper. As the moderate political-diplomatic tactics of the elite Palestinian leaders failed to achieve any gains for the national cause, a new tone of militancy started to dominate newspaper articles, reports, and public speeches challenging the traditional notables’ leadership. This militancy gained stronger ground when the British authority hanged three Palestinian heroes—Muhammad Jamjum, Fu’ad Higazi, and Ata alZayr—who had participated in the August 1929 disturbances. The execution of the three martyrs led to a general strike and a commemorative celebration.

The challenge to the executive leadership manifested itself politically as well as militarily. A new political party called alIstiqlal (Independence Party) was founded in August 1932. This group promoted active opposition to both the

British and the Zionists, and opposed the moderate methods of the executive as ineffective and nonproductive. The leaders of the new party—Akram Zu’ayter, Awni Abd al-Hadi, Izzat Darwaza, and Ahmad al-Shuqayri—were independent, intelligent, articulate men who appealed to the emerging militant youth.

A stronger challenge to the elite leaders came from a secret religious organization led by Sheikh Izz alDin alQassam, a man of integrity and eloquence. AlQassam was born in Syria; he took refuge in Palestine in the early 1920s after being sentenced to death by French colonial authorities for leading the resistance to French occupation. He settled in Haifa among the urban poor and displaced peasants. He founded al-Istiqlal Masjid (Independence Mosque), where he preached his revolution (jihad), attracting workers as well as peasants from nearby villages, buying weapons, and training fighters. He spoke out fiercely against British rule and Zionist colonization, advocating spiritual renewal and political militancy as the appropriate means for defeating these dangers and achieving national goals. In the mid-1920s al-Qassam contacted the mufti of Jerusalem and demanded that waqf money be spend on arms rather than mosque repairs. Amin, who did not believe in military struggle, rejected this demand.

In November 1935, al-Qassam and his men took to the hills of northern Palestine with the aim of raising the countryside in revolt. AlQassam’s guerrillas were am bushed in Ya’abad Forest, where the sheikh and three of his followers fell in bat tle with British forces on November 20, 1935. The martyrdom of al-Qassam and his men electrified the Palestinian masses. A large number of youths throughout Palestine formed guerrilla bands, calling themselves Ikhwan alQassam (Brothers of al-Qassam). Indeed, al-Qassam achieved more in death than he did during his fifteen years of preaching.

The Revolt of 1936–1939

On April 15, 1936, Ikhwan alQassam killed two Jews in a bus ambush; this triggered retaliation by the Hagana, who murdered two Palestinians. These incidents were followed by counterattacks and killings in Jaffa and Tel Aviv; and on April 19, 1936, the Palestinians launched the general strike that evolved into the 1936–1939 revolt.

The strike was declared on April 19, 1936. The decision to strike was taken by committees in Nablus, Jaffa, Haifa, and other cities and towns throughout Palestine. The committees were composed of Istiqlalists, Ikhwan alQassam, and other nationalist groups. The Istiqlalists wanted to widen support for the strike; so they contacted the Palestine Arab Party headed by Jamal al-Husseini, the National Defense Party headed by Raghib al-Nashashibi, the Reform Party headed by Husayn al-Khalidi, the National Bloc headed by Abd al-Latif Salah, and the Youth Congress headed by Ya’qub al-Gusayn. The representatives of the above-mentioned parties formed the Arab Higher Committee (ACH), with Hajj Amin as president. The Christian community was represented by Alfred Rock, a Greek Catholic, and Ya’qub Faraj, a Greek Orthodox Christian. Awni Abd alHadi and Ahmad Hilmi Abdul alBaqi were elected general secretary and treasurer respectively. Thus the committee represented all factions: moderates and radicals, Muslims and Christians. The actual leadership in the first few months was in the hands of young radicals with whom the AHC consulted before making public statements or policy decisions. The committee declared its determination to achieve three major demands: first, a complete halt to Jewish immigration; second, a prohibition on the transfer of Arab lands to Jews; and third, the establishment of a national government responsible to a represen tative council.

The British response to the strike was extremely harsh, aimed at crushing the civil disobedience. The mandate government enacted regulations authorizing deportation, collective punishment, and search without warrant. Other actions followed: arresting Arab leaders or deporting them to the Seychelle Islands in the Indian Ocean, imposing tough curfews, closing down newspapers, bringing reinforcements from Egypt and Malta, and increasing the Jewish police force. The British also permitted the use of Tel Aviv port to replace the Jaffa port, which was crippled by the Arab strike, to receive Jewish immigrants. These harsh measures taken by the British antagonized the Palestinians further, pushing the civil disobedience into full-fledged revolt and armed struggle.

Although Hajj Amin, under public pressure, accepted the Arab Higher Committee’s presidency, he did not wholeheartedly adopt the tenets of the revolt. The revolt had a force of its own that he could not control and which, in fact, forced him into a position he was hesitant to adopt. The mufti tried to limit the general strike and to keep it from becoming a violent revolt. During the first few months he vacillated, not knowing which course to take. The high commissioner apparently was aware of the dilemma in which the mufti and other members of the committee had placed themselves. In a letter to the colonial secretary, Hajj Amin expressed his understanding of the behavior of those leaders. He understood their position and the demand of the Palestinian masses that forced them to support the strike. The high commissioner realized that at that moment the notables were powerless and would have to endorse the strike. The British requested an end to the strike from the Arab Higher Committee, proposing in return to appoint a royal commission to look at the Palestinian grievances. Although the Arab Higher Committee rejected the offer, on May 15, 1936, the pro-mufti newspaper al-Liwa issued an appeal calling upon the public to avoid violence and to use peaceful means. 297

As the revolt became more widespread and violent, the British took harsher actions, including blowing up houses of Palestinians suspected of harboring rebels, attacking and damaging mosques, and imposing fines on villages supporting the rebellion. In response to these measures, the Arab Higher Committee repeated its appeal to the Palestinians not to resort to violent actions. At the same time, the committee called on the rulers of the neighboring Arab countries to intervene on their behalf with the British government. Hajj Amin did not want Transjordan’s Emir Abdullah to intervene, because of his involvement with the British, the Nashashibis, and the Zionists. However, Abdullah had received a suggestion from Moshe Shertok of the Jewish Agency that the Jews would support Abdullah as the head of the Palestinians if he recognized the Zionists’ interests in Palestine. In addition, Nuri alSa’id of Iraq and Ibn alSa’ud of Saudi Arabia sent an appeal to the Higher Committee to end the general strike and the rebellion, because “We rely on the good intentions of our friend Great Britain, who has declared that she will do justice.” The commit tee accepted the appeal. 298

The British then appointed a royal commission called the Peel Commission to investigate the reasons behind the uprising. It arrived in Palestine on November 11, 1936, and published its report on July 7, 1937. This commission concluded that the cause of the revolt was the Arab fear of the establishment of the Jewish national home and their desire for national independence. It recommended the abolishment of the mandate except in a “corridor” surrounding Jerusalem, stretching to the Mediterranean coast at Jaffa. It also recommended a partition plan, creating a Jewish state in the mid-west and north of Palestine; and an Arab state in the south and mid-east. The part allotted to the Palestinians was to be united with Transjordan, under the rule of Emir Abdullah. The Peel Commission recommended the exchange of population, which would affect 225,000 Arabs and 1,250 Jews, even if such an exchange took the form of compulsory transfer. 299

On July 8, 1937, the Higher Committee sent a long memorandum to the British government in response to the Peel Commission’s proposal. The memorandum, signed by the mufti, demanded the cessation of immigration and of land sales to Jews, and the establishment of a national democratic government, with a treaty agreement safeguarding Britain’s interest in Palestine and protecting all legiti mate rights of the Jews. The mandate authority viewed the mufti’s response as a deviation from his usual cooperative behavior, and on July 17, 1937, Wauchope, the British high commissioner, sent the police to arrest the mufti while he was attending a committee meeting. Warned in advance (perhaps by a British friend), he escaped through a back door to the Haram al-Sharif. (He stayed in the Haram, conducting his duties as the head of the Higher Committee, until the night of October 14, 1937, when he climbed down the walls of the Haram, was driven to Jaffa, and fled to Lebanon.) 300

Violence resumed in late July and August 1937. The mufti, who was still in the Haram, appealed to the Palestinians to refrain from violent action. But in September 1937, L. Y. Andrews, the district commissioner of Galilee, was murdered by Palestinian extremists. The mandate authority’s reaction was very harsh. The Arab Higher Committee was declared illegal, and two hundred leaders were arrested and deported to the Seychelles. The rebellion escalated in October, after Mufti Hajj Amin left Palestine. A rebel headquarters known as al-Lajna al-Markaziyya li-l-Jihad was set up at Damascus, administered by Izzat Darwaza under the guidance of the mufti. The role of the committee in Damascus was not to control the rebels’ activities in Palestine, but to coordinate between the rebels and the exiled political leadership. Another important function of the Damascus committee was the dissemination of information about revolutionary activities. The local rebel leaders were completely independent. 301 The revolt was autonomous and spontaneously organized in the countryside. The rebels organized themselves into guerrilla bands ( fasa’il) of a few men with a leader (qa’id). Guerrilla fasa’il often used hit-and-run tactics, at night and usually in their local areas. Later on, and after the arrival of Fawzi al-Qawuqji, a military man of Syrian heritage, the guerrillas operated under a regional or national command structure. They became more effective upon integration into a nationally coordinated structure. Often, however, they responded spontaneously when British troops advanced on or encircled neighboring villages. The local guerrilla bands had the advantage of small size and knowledge of the terrain to escape and hide among their people.

Recruitment of fighters varied from voluntary enrollment to selection by family (hamula) to selection by village elders. Taking care of the tha’ir (rebel) was the responsibility of the whole family; they collected money to purchase his rifle and provide for all his needs. Peasant families contributed men, money, food, and shelter enthusiastically. The rebels gained control of much of the countryside. They developed systems of taxation for supplies and armaments. Rebels also had their own courts to settle disputes among villagers, as well as to rule in civil conflicts and criminal cases.

The revolt intensified and reached its climax in the summer of 1938. Major Palestinian cities, including Jerusalem, joined the rebellion. This development prompted the British to launch an all-out campaign to crush the revolt. They had two divisions, squadrons of airplanes, the police force, the Transjordan frontier forces, and six thousand Jewish auxiliaries. British forces outnumbered the Palestinians ten to one. The British utilized other tactics, such as encouraging and assisting disaffected notables and their peasant clients to establish local counterrevolutionary groups called “peace bands.” These groups were used as informers or fighting forces to battle the rebels.

During the revolt years, the Arab community suffered nearly twenty thousand casualties (5,032 dead and 14,760 wounded). About 110 were hanged. And by the end of 1939, the Palestinian people became exhausted; the harsh measures utilized by the British at last succeeded in suppressing the revolt. The Palestinian parties were made illegal, Palestinian leaders were detained, thousands of activists and fighters were put in prisons or concentration camps, and the community was disarmed.

In May 1939, the British government issued a White Paper that declared its opposition to Palestine becoming a Jewish state. It stated that Jewish immigration would be limited to 75,000 over the next five years and that land sales would be strictly regulated, and affirmed that an independent Palestinian state would be established over the next ten years, with interim steps toward self-government. The implementation of the 1939 White Paper’s policies was not conditional on Palestinian or Zionist acceptance; in fact, the provisions concerning immigration and land transfer were implemented.

The Mufti in Exile

Mufti al-Hajj Amin al-Husayni tried to lead the Palestinian National Movement from his exile in Lebanon, and to resume the armed struggle. However, Palestinian society was economically devastated, and had been politically and militarily crushed as a result of the harsh British policies. The French in Lebanon restricted Hajj Amin’s political activities, and he was under virtual house arrest. The French were pressuring him to announce his support for the Allies. Under such pressure, he had no choice but to escape to Iraq. He arrived in Baghdad via Syria on October 13, 1939.

In Baghdad, the Iraqi politicians, including the pro-British prime minister Nuri alSa’id, welcomed him. The British asked the Iraqi prime minister to obtain a promise from the mufti not to get involved in politics. He pledged not to interfere in Iraqi politics, but his pledge did not include, in his mind, political activities on behalf of Palestine and the Arab nationalism.

The Iraqi public regarded the mufti as the leading Arab nationalist. He spent the first few months establishing personal relationships with the political and military elite. The Iraqi people resented the politicians who were collaborating with the British, especially Nuri al-Sa’id. Complete independence and an end to British control over Iraq was on the mind of all Iraqis, as were the Palestine question and the British atrocities against the Palestinians. Between November 1939 and June 1940, thirty Arabs were condemned to death in Palestine in secret British trials. Nuri alSa’id refused a request from the mufti to intercede with the British to spare the life of a rebel. The mufti became furious, telling an Iraqi friend that the Arab nation would be threatened with ruin if people like Nuri were to direct its affairs.

Nuri was unpopular; in fact, many considered him a traitor. 302 He resigned and was replaced by Rashid Ali al-Kilani in March 1940. Al-Kilani needed the support of the “Golden Square,” a Pan-Arab anti-colonialist group of four officers who had been an important factor in Iraq politics since the late 1930s. The mufti invited the colonels, with whom he had considerable influence, to his house and convinced them to support al-Kilani.

In July 1940, the Iraqi government made an attempt at conciliation between the British and the mufti. A firm proposal was drawn up in which the mufti accepted the White Paper of 1939 as the basis for settlement of the Palestine problem. In return for British implementation of the White Paper—which restricted Jewish immigration into Palestine to 75,000 over a five-year period, restricted land purchases, and pledged independence for Palestine, with an Arab majority, after ten years—the mufti agreed to support the British war effort, and the Iraqis would supply two divisions to fight with the British forces. Winston Churchill rejected this proposal; at the same time, he accepted the Zionist request to organize a Jewish brigade in Palestine. 303

These events prompted the mufti to prepare for a revolt against Britain and France. A secret Arab committee composed of leaders from Syria, Iraq, Palestine, and Transjordan was established. Their goal was to achieve independence through rebellion and then to unite the liberated Arab countries into an Arab nation. Mufti Amin then conducted negotiations with the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) between July 1940 and April 1941, aimed at receiving material and diplomatic support for the revolt.

The mufti, by the late 1940s, was considered the most influential and respected man in Iraq. The British considered kidnapping or killing him. Churchill approved his assassination in early November 1940. General Percival Wavell, head of the Middle East Command, ordered the release, from a Palestine jail, of David Raziel, a leader of the outlawed underground Zionist organization Irgun, and a few of his companions, and assigned them mission of going to Iraq and assassinate the mufti. However, a German plane killed this terrorist group on May 20, 1941, before they could carry out their mission.

On April 1, 1941, a military coup led by the four colonels of the Golden Square established a new regime in Baghdad and named al-Kilani as prime minister. The British responded by sending reinforcement troops from India, Palestine, and Transjordan. After a month of fighting, the British forces crushed the Iraqi forces. The four colonels were captured and hanged by the pro-British government of Nuri al-Sa’id. The mufti and his colleagues managed to escape from Baghdad on the night of May 29, 1941, arriving in Iran, where Riza Shah gave them political asylum. In June–July of 1941, Britain and Russia invaded Iran, and Riza Shah abdicated in favor of his son Muhammad Riza, who agreed to cooperate with the British. Hajj Amin remained in hiding in Tehran for several weeks. Then, on September 23, 1941, he managed to escape to Italy via Turkey and Bulgaria.

The mufti met with Mussolini in Rome in October, 1941, where he outlined the Arab aspirations: full independence for all parts of the Arab world and the rescue of Palestine from British imperialism and Zionism. He was encouraged by Mussolini’s response; however, he was hoping for a public declaration to follow the private conversation. After two days in Italy, he left for Berlin to speak with Hitler, meeting him on November 28, 1941. Again he stated the Arab national aspirations and requested a public declaration from Hitler stating unequivocal support for the Arab cause. Hitler firmly opposed such a declaration; instead, a secret agreement was reached wherein Germany and Italy were ready to “grant to the Arab countries in the Near East, now suffering under British oppression, every possible aid in their fight for liberation; to recognize their sovereignty and independence; to agree to their federation if this is desired by the interested parties; as well as to the abolition of the Jewish National Homeland in Palestine.” 304

After the defeat of Germany in 1945, the mufti left Austria for Paris, where he was placed under “residential surveillance.” He later managed to escape to Egypt, where King Faruq granted him protection and hospitality. He continued to support the cause of Arab independence until his death in Beirut, Lebanon, in 1974.

Husayn bin Ali and His Sons

Husayn bin Ali, formerly the sharif and emir of Mecca and king of the Hijaz, became alienated from the British, in spite of his critical support for the Allies during the First World War, because of his resistance to Zionism and his refusal to endorse the Balfour Declaration. The British not only stood by as the Hijaz was attacked by Ibn Saud from the east, but also began lending support to the Saudis. Husayn was forced to abdicate to his son Ali, and was eventually exiled to Cyprus by the British, who imprisoned him there; shortly afterward, the Hijaz was annexed by the Saudis. Ali spent the rest of his life in Iraq.

Husayn was deeply disappointed by the willingness of his sons Faysal and Abdullah to collaborate with both the British and the Zionists, especially when they accepted Britain’s policies in exchange for the kingships of Iraq and Transjordan respectively. He never reconciled with Faysal, but in his old age, as he became infirm, he returned to Amman to live with Abdullah. He died in 1931 and was buried as a caliph in the al-Aqsa mosque compound. 305

Faysal remained king of Iraq until he died of a heart attack in 1938. He was succeeded by his son, and Iraq remained under Hashemite rule until the monarchy was overthrown in 1958.

The Hashemite line remains today with the monarchs of Jordan, who are descended from Husayn’s son Abdullah. Abdullah was briefly succeeded by his son Talal, then by his grandson Hussein, who ruled under the guardianship of Glubb Pasha until he became of age. Abdullah was assassinated at Al-Aqsa Mosque by a Palestinian nationalist in 1951, and was buried there next to his father.

1940–1947 and the Partition Plan

The Palestinian National Movement suffered a major setback between 1940 and 1947, after the collapse of the three-year rebellion, as a result of harsh British policies. Palestinian society was economically devastated, politically and militarily defeated, and psychologically crushed. In 1940, of the three major Palestinian political groups—the Nashashibis, Istiqlalists, and the Husaynis—the only faction that survived were the Nashashibis. However, their relationship with the British and the Zionists minimized their role and diminished their influence in the Palestinian community. In 1942, the Istiqlalists and the Husaynis reorganized their parties: the Arab Higher Front of the Istiqlalists, and the Arab Higher Committee of the Husaynis were established in an effort to revitalize the Palestinian National Movement. Through 1944 and 1945, all attempts to unite or coordinate the activities of both parties failed. Representatives of seven Arab states—Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Transjordan, Lebanon, and Yemen—met in Alexandria between September 25 and October 7, 1944, to establish the Arab League. The Palestine question was an important factor behind the establishment of this organization. A special resolution on Palestine was declared at the end of the meeting, stating: “Palestine constitutes an important part of the Arab world, and the rights of the Arabs cannot be touched without prejudice to peace and stability in the Arab world.”

The Arab League Council met in Bludan, Syria between June 8 and 12, 1946. The Palestine question was the main issue on the agenda. The council forced the two Palestinian parties to form a leadership committee composed of five members representing the two groups, headed by Hajj Amin. In January 1947, the mufti added five more members, four of whom were loyalists and yes men.

In contrast to the weak and disorganized Arab community, the Jewish community in the 1940s was stronger economically, more organized politically, and significantly stronger militarily. The Zionist movement was able to mount a vigorous diplomatic, and political campaign against the policies of the White Paper. On May 11, 1942, a Zionist conference convened at the Biltmore Hotel in New York, where a new Zionist program was announced. The conference not only announced its opposition to the 1939 White Paper and demanded open immigration into Palestine, but went much further, calling for a Jewish state in all Palestine. The Zionists firmly declared their intention to end Arab existence in Palestine. The Biltmore Convention was the first official indication of the Zionist ethnic cleansing plan; the Zionists were open about their intention to transfer the Palestinian Arab population out of Palestine. Prior to 1942, they had been very careful in discussing these plans. 306

In 1937, BenGurion, in response to the Peel Commission’s partition proposal, addressed the Zionist Executive: “After the formation of a large army in the wake of the establishment of the state, we will abolish partition and expand to the whole of Palestine,” He wrote to his family during the same period: “A Jewish state is not the end but the beginning . . . we shall organize a sophisticated defense force—an elite army. And then I am sure that we will not be prevented from settling in other parts of the country.” 307 He also wrote to his son: “The Arabs will have to go, but one needs an opportune moment for making it happen, such as war.” 308

On December 13, 1938, Moshe Sharett, Ben-Gurion’s second in command, in a lecture to employees of the Zionist Organization in Jerusalem, talking about the purchase of 2,500 dunums (six hundred acres) of land in the Baysan Valley, stated: “There is a tribe that resides west of the river; the purchase of their land will in clude paying the tribe to move east of the river; by this we will reduce the number of Arabs in Palestine.” 309 In 1940, Yousef Weitz, the director of the Jewish National Fund, wrote: “It is our right to transfer the Arabs . . . The Arabs should go.” 310

Shortly after the Biltmore Convention, the Zionists carried out an intensive campaign in the United States, targeting the members of Congress. At the end of World War II, sixtytwo senators and eightyone congressmen wrote President Roosevelt supporting the Zionists’ rights to Palestine. In January 1944, the US Congress, in a joint resolution, endorsed the Biltmore program. And by August 1945, President Truman called on the British prime minister to allow 100,000 European Jews to immigrate to Palestine. 311

The involvement of US in the future of the Middle East started officially with the formation of the Anglo-American committee of inquiry in 1946 (Morrison Grady Committee). The committee adopted the American position, calling on the mandate government for the immediate acceptance of 100,000 Jewish refugees from Europe into Palestine. During World War II, Jews in Palestine volunteered in large numbers to serve in the British army, serving mainly in North Africa. Although the mandate government implemented the White Paper policies regarding Jewish immigration and land transfer, the Zionists continued to coordinate and cooperate with the British. Some of the Zionist leaders in Palestine were advocating opposing the British, but in September 1939, Ben-Gurion issued a call for Jews to support the British in the war: “We must assist the British army as though there were no White Paper; and we must oppose the White Paper as though there were no world war.” 312

The Stern Gang (also called Lehi), a Jewish terrorist organization, attempted to form an alliance with the Nazis in exchange for their help in establishing a Jewish state and allowing the Jews of Europe to immigrate to Palestine. Such contacts with the Nazis prompted them to start military activities against British forces in Palestine in 1941. 313 The Jews in Palestine did not welcome this military campaign; on the contrary, the terrorists became isolated and outcast. 314 However, near the end of the war, in February 1944, the Irgun, under the leadership of Menachim Begin, ended the wartime truce with the British and started blowing up British offices related to immigration and tax collection. In November, the Stern Gang assassinated Lord Moyne, the British minister of state in the Middle East and an outspoken critic of political Zionism, outside his home in Cairo. After the war, in October 1945, the Hagana entered an alliance with the Irgun and ceased cooperation with the British. The whole Jewish military joined together in the campaign against the British, which gradually intensified and reached its climax in 1946 with the bombing of the King David Hotel by the Irgun, which killed ninety-one people. The British responded to this terror campaign with restraint, in complete contrast to their response to the Palestinian revolt. Between August 1945 and September 1947, only thirty-seven Jewish terrorists were killed. Even in the aftermath of the hotel bombing, members of the Jewish Agency were only detained for a little over three months. 315 Though Lord Moyne’s killers were hanged, when their bodies were returned to Israel by Egypt in 1975, they were received as heroes, and commemorated on postage stamps. 316

Ben-Gurion led the Zionist movement from the mid-1920s into the 1960s. The 22nd Zionist Congress, in 1946, entrusted Ben-Gurion with the defense portfolio, giving him complete control over all security issues of the Jewish community in Palestine. In the final days of August 1946, he gathered together the leadership of the Zionist movement in a hotel in Paris, the Royal Monue, to formulate a plan to take over all of Palestine. He accepted the principle of partition; however, he demanded a large chunk of Palestine—80 to 90 percent of mandatory Palestine. A few months later the Jewish Agency translated Ben-Gurion’s “large chunk of Palestine” into a map showing a Jewish state that anticipated almost to the last dot pre-1967 Israel; i.e., Palestine without the West Bank and Gaza strip. 317

During the deliberations in Paris, the Zionist leaders never considered the possibility of any resistance from the Palestinian Arab population. The Zionist leadership was aware of the total collapse of the Palestinian resistance. The desperate situation of the indigenous population of Palestine was obvious. The British mandatory authorities were the only ones standing between them and the plan of declaring their state. The struggle against the British resolved itself when the British decided, in February 1947, to transfer the Palestine question to UN. 318

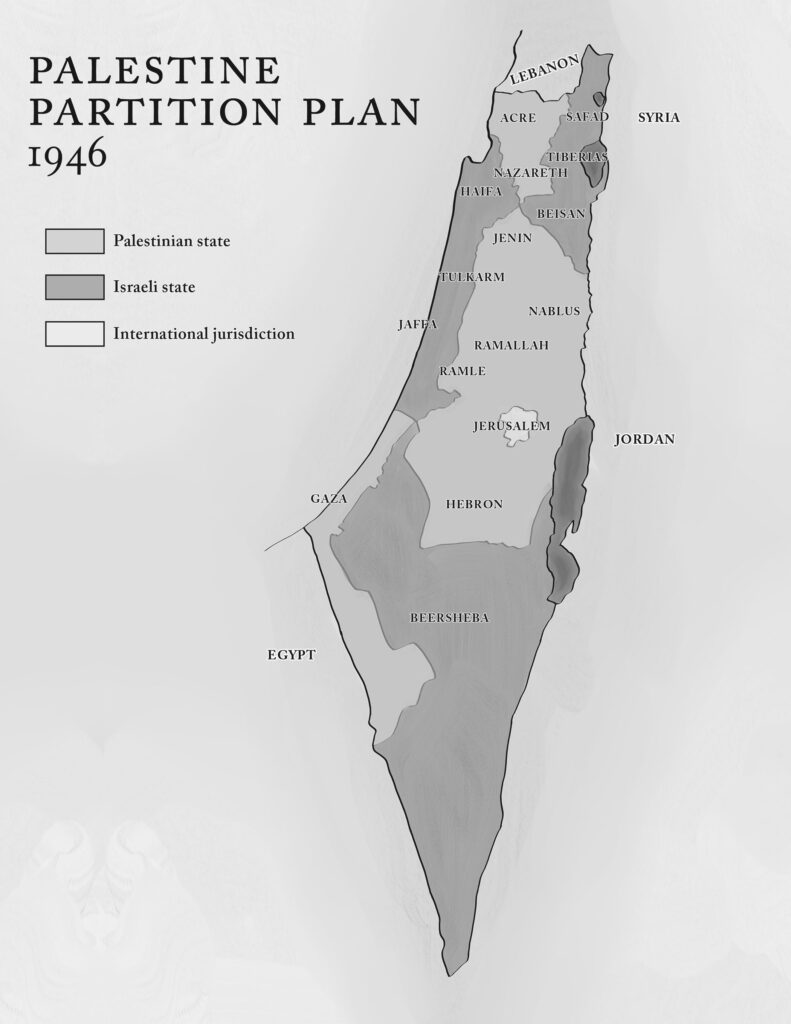

On February 7, 1947, the British government announced its intent to terminate the mandate for Palestine; and on April 2, 1947, formally asked the United Nations to make recommendations regarding the future government of Palestine. On May 15, 1947, the UN appointed the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP). On August, 31, 1947 (UNSCOP) released its report, which included the unanimous recommendation to terminate the mandate and to grant Palestine independence at the earliest possible date. A majority of the committee members recommended the creation of independent Arab and Jewish states, with Jerusalem to be placed under international administration. On September 23, 1947, the General Assembly established an ad hoc committee on the Palestinian question to consider the UNSCOP report. The ad hoc committee made a number of boundary changes to the UNSCOP recommendations. On November 26, 1947, the General Assembly vote was postponed, as the United States was still campaigning to secure the necessary two-thirds majority of the valid votes (not counting abstaining and absent members) needed to approve the partition plan. In the end, the United States government, through applying pressure and threats, succeeded in securing the needed votes for the approval of Partition Resolution 181. On November 29, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly voted thirty-three to thirteen, with ten abstentions and one absence, in favor of Resolution 181.

The Jewish Agency and the mainstream Zionist leaders accepted the partition resolution with jubilation, while the Revisionist Zionists (Irgun and Stern leaders) rejected it. Begin, the Irgun’s leader stated, “The bisection of our homeland is illegal.” The mainstream Zionist leadership acceptance of the partition resolution, however, was a tactical acceptance; acceptance of partition did not mean acceptance of the boundaries of the Jewish state as stated in the resolution. Between the UN vote on November 29, 1947, and the declaration of the state of Israel on May 14, 1948, a number of developments enabled the Zionists to acquire more land and to expel the Palestinians from the Jewish state. 319

On December 3, 1947, David Ben-Gurion declared before the Histadrut Executive:

In the area allotted to the Jewish state there are not more than 520,000 Jews and about 350,000 nonJews, mostly Arabs Such a composition does not provide a stable basis for a Jewish state [it] does not even give us absolute assurance that control will remain in the hand of the Jewish majority.

. . . though Jerusalem under the partition plan was not designated as the capital of the Jewish National State, it must be, not only a great and expanding center of the Jewish settlement, but also the center of all Jewish national and international institutions. We know there are no final settlements in history, there are no eternal boundaries, and are no final political claims, and undoubtedly many changes and revisions will yet occur in the world. 320

The Palestinians rejected the partition resolution, as they saw it as illegal and immoral. Walid Khalidi articulated the Palestinian position as follows: “The native people of Palestine, like the native people of every other country in the Arab world, Asia, Africa, America, and Europe, refused to divide the land with a settler community.” 321 The resolution incorporated the most fertile land in the proposed Jewish state. Nearly all the citrus land, 80 percent of the cereal land, and 40 percent of Palestinian industry would fall within the borders of the Jewish state. The designated Jewish state also included four hundred out of more than a thousand Palestinian villages. 322

The injustice of the partition resolution was egregious: it handed the Jews, who owned less than 6 percent of the total land area of Palestine and constituted no more than one-third of the population, more than half of its overall territory. The most immoral aspect of Resolution 181 was that it included no mechanism to prevent the ethnic cleansing of Palestine. 323 Resolution 181 was an assured recipe for the tragedy that began to unfold the day after it was adopted. On 42 percent of the land, 818,000 Palestinians were to have a state that included 10,000 Jews, while the state for the Jews was to stretch over 56 percent of the land that 499,000 Jews were to share with 438,000 Palestinians. The UN members who voted in favor of the partition resolution contributed to the crime of ethnic cleansing that was about to take place. 324

Conspiring with Emir Abdullah

Transjordan had been excepted from the British mandate in 1923, but placed under British supervision. In 1928, Transjordan and Britain concluded an agreement that gave Britain control of the country’s foreign policy, finances, and armed forces, and stipulated that a constitution be established. The Transjordan army—the Arab Legion—included a desert force of Bedouins organized by British officer John Bagot Glubb (known as “Glubb Pasha”), who later commanded the entire legion. In the Transjordan Colonial Office, Churchill was the British colonial secretary and T. E. Lawrence his chief adviser. To the chagrin of his father, King Husayn of the Hijaz, Emir Abdullah worked willingly with the British in exchange for recognition of Transjordan. For the British, the existence of Transjordan established a buffer zone between Palestine and the Saudi-ruled regions to the east; furthermore, as a purely Arab state, it was a place that could accommodate Palestinians if the Jewish presence in the country eventually pushed them out. 325 And indeed, the Zionists had no intention of accepting the limits of the partition resolution. Their real intention was to take over most of Palestine and to prevent the establishment of a Palestinian state through a secret agreement with Abdullah, whose annexation of the territory allotted for a Palestinian state was to be the first step in his dream of a Greater Syria. 326

Abdullah accepted the Jewish national home idea early on, even in the 1920s. He was in no position to antagonize Britain; at the same time, he sought financial help from the Zionists. In the early 1930s, he told the Jewish Telegraph Agency, “The Jews of the world will find me to be a new Lord Balfour, and even more than this; Balfour gave the Jews a country that was not his; I promise a country that is mine.” 327 And in early August 1946 he met secretly with Eliyahu Sasson, the head of the Arab department of the Jewish Agency, where he stated his plan to expand Transjordan by annexing the Arab sector of Palestine as a first step, to be followed by the annexation of Syria. Abdullah asked Sasson to bring, in the next meeting, the first ten-thousand-pound payment of a total sum of forty thousand pounds for expenses during the Syrian parliamentary election, and to set up a new representative body in Palestine replacing the Higher Committee. 328

In August 1947, Umar Sidqi Dajani, a Palestinian Arab leader close to Abdullah, traveled to Europe at the expense of the Jewish Agency to present to UNSCOP members Abdullah’s position in support of partition and proposing the annexation of the Arab part of Palestine. On November 17, Abdullah himself met, on the northern border, with Golda Meir, Ezra Danin, and Elyaho Sasson. According to Danin and Sasson, Abdullah assured Meir that he would not attack the partitioned Jewish state, but that he would annex Arab Palestine. In April 1948, Abdullah had another meeting with an Israeli representative, and once again it was agreed that Abdullah would control Arab Palestine if he did not interfere with efforts to set up a Jewish state. 329

Britain Withdraws

The British government did not endorse the partition plan, and was among the abstaining members of the General Assembly. During the deliberations in the UN, the British government “did not feel able to implement” any agreement unless it was acceptable to both the Arabs and the Jews, and asked the General Assembly to provide an alternative implementing authority if that proved the case. Britain ultimately announced that it would accept the partition plan, but refused to implement the plan by force, arguing it was not acceptable to either side. And on December 11, 1947, Britain announced that the mandate would end at midnight on May 14, 1948, and that it would completely withdraw its forces and administration by August 1, 1948. They assumed no responsibility for the preservation of law and order. When they decided to withdraw completely on May 14, they notified only the Jewish Agency, excluding the Arabs, who were caught by surprise.

On May 14, 1948, the Zionists declared the state of Israel.

Eleven minutes later, the United States recognized the state of Israel.