The past does not and can no longer exist. Archaeological materials and texts—remnants of the past—do exist. When we write history today, we attempt to explain, understand and describe these fragments of the past. History is interpretation of data that exists now. This is why we cannot write history without evidence. It is also why what we write is so fragmented and partial. We are ignorant of most of the past. And that is the beginning of wisdom in history-writing. 1

Palestine and the Palestinians

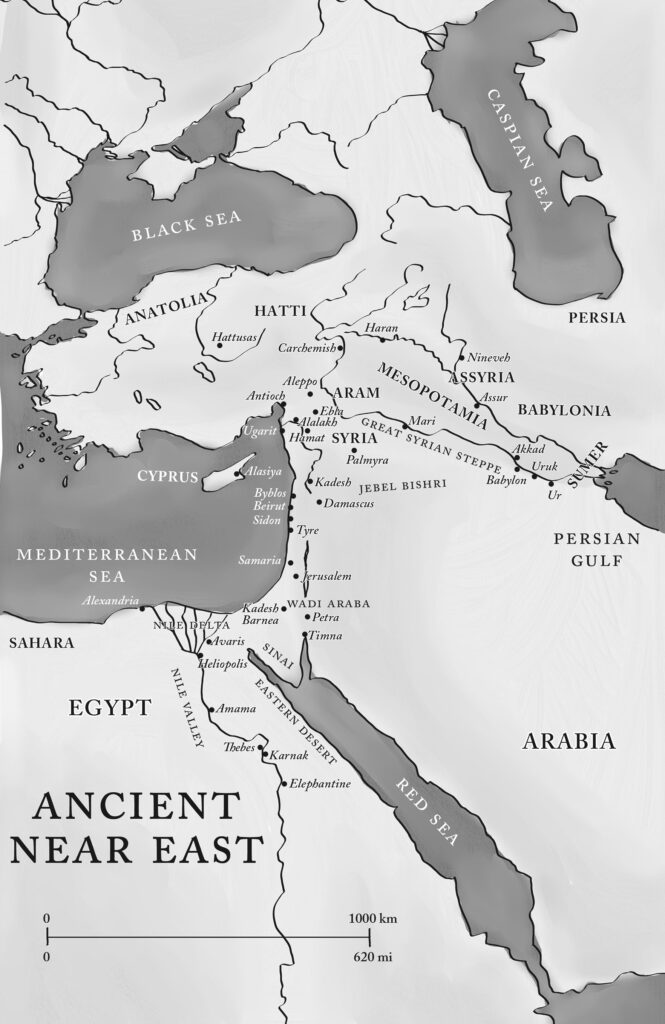

Palestine is defined as the area of southern Levant on both sides of the Jordan rift. Geographically, it is best understood as the southern fringe of Syria. It includes highlands intersected by low-lying valleys. Large areas of treeless steppeland are found in the south and east where it joins the Arabian and Sinai deserts. The land is mentioned in the Egyptian texts as the Upper Retenu and Kinahhi (Canaan), but it has been known as Palestine since the Assyrian period (1300–600 BCE). The name Palestine was also used by Herodotus, the Greek historian of the sixth century BCE, and the Romans continued to refer to it by that name. In modern times, the name Palestine was used during the British mandate period. 2

Until the 1950s and the 1960s, the Old Testament was the main source of the history of Palestine. Western historians based their history of Palestine and the Near East on biblical accounts without any support from historical records or archeological findings. During the second half of the twentieth century CE, many historians challenged accounts which used biblical stories as their reference. By the 1980s, several publications by prominent scholars presented a new history of Palestine based on the tools of historic research supported by archaeological study. Those are the sources utilized in the current narrative of the ancient history of Palestine.

The ancient Egyptians, Babylonians, and Assyrians left behind texts that have enabled historians to construct real histories of these nations based on their content, as well as material remains extracted through excavations. In the case of ancient Palestine, the absence of textual data forced modern historians to depend to a great degree on archaeological research in their effort to construct the real history of ancient Palestine. They also utilized information from relevant contemporary textual documents which have been discovered recently in Ugarit, and from textual records of Egypt and Mesopotamia. Still some historians considered admitting material drawn from biblical narratives. “In the main, however, the historic reconstruction of the Palestinian civilization has had to depend on the results of archaeological research undertaken in the Levant during the past one hundred and fifty years or so.” 3

Nowadays, scholars who are involved in the reconstruction of the history of ancient Palestine rely on the skills and knowledge developed by the pioneers in this field. Sir Flinders Petrie (1853–1942) is considered to have led these efforts. He was the first to recognize that the artificial hills or tells which are numerous throughout the landscape of the Near East “represent in themselves artifacts consisting of accumulated occupation debris resulting from the continued occupation of the same site generation after generation. . . . He believed that with careful excavation it ought to be possible to peel off the layers one after the other, from the top downward, revealing the history of occupation in reverse order.” 4 The site at which he chose to put his idea to the test was Tell el-Hesi in southern Palestine, which he excavated in 1890. Through his work at Tell el-Hesi, Petrie laid the foundations for two methodological disciplines: stratigraphy—the analysis of occupation layers—and pottery chronology, the analysis of pottery from successive layers.

Palestine in the Ancient Near East

Palestine held a unique position in the ancient history of the Near East. Major historical developments resulting in prosperity or decline in the country were related to the status of rainfall and access to water resources. Palestine did not have a steady water supply, unlike both Egypt and Mesopotamia, which had major rivers. The geography of the land and the diversity of its regions, comprising narrow coastal plains, rugged hills and mountains, deserts, valleys, and inland plains, prevented the development of a central authority and trans-regional statehood.

Being a bridge between three continents of the ancient world, Palestinian society was influenced greatly by the neighboring powers, especially Egypt and Mesopotamia, and over extended periods of time, was controlled economically and politically by these powers. Palestinian society was also affected by major waves of migrants, whose migration from other regions was prompted by climate changes and severe prolonged droughts in these regions. The first major documented one was the North African migration wave, which resulted from an extended drought that occurred at the end of the seventh millennium and continued through the fifth millennium BCE. The next major one was the Mycenaean migration wave, which followed a severe extended drought in the northeastern Mediterranean basin around 1200 BCE, which lasted for two centuries. In both cases, the refugees from these regions were integrated with the indigenous people of Palestine. During the eras of Assyrian and Babylonian rule, population transfer policies were enacted by which the Palestinian population was transferred to other parts of the empires, and other populations were brought to Palestine. During the era of Persian rule, many of those who had been deported from Palestine returned. Other invaders during the different periods of the ancient history of Palestine, including the Macedonians and Romans, established their own settlements. All these factors shaped the history of Palestine and Palestinian society.

Palestine’s population has paid a high price for its endurance. The imperial policies of deportation and genetic mixing failed to interrupt this historical continuity. Territories were conquered and cities were destroyed, but many Palestinians remained in the region and preserved the language, culture, religion, and way of life for the returnees. Professor Thomas Thompson eloquently defined the Palestinian people and traced their ancient history as far as the Neolithic Age. He concludes:

The history of Palestine, which we have traced from at least the late Neolithic period, reflects a continuity of the people of Palestine. . . . The social and cultural continuities of Palestine’s population from that time are marked and unequivocal. We see them in the material remains and particularly in the styles of pottery from cooking pots and storage jars, as well as in the later development of lamps and common ware. We find them in the structures of the economy, the political structures of patronage, the types of settlement, even the continuity of the trade routes . . . the development of religious beliefs was also progressive, involving as much a reinterpretation of the old as an introduction of the new. . . . As Judaism gave way to the dominance of

Christianity in the Byzantine period in the course of the fourth century CE, and when both Christianity and Judaism gave place to Islam in the seventh, changes took place in the religious thoughts of the population,

but such changes were developmental and incremental. 5

The history recounted in this book will show that the Canaanites and Amorites were the indigenous inhabitants of Palestine-Syria going back to the Neolithic period. They were not invaders from Arabia. Since the Neolithic Age, and over thousands of years, Palestine-Syria was slowly and gradually populated with immigrants from different regions who became integrated and fully assimilated with the indigenous inhabitants. This slow and continuous process brought to Palestine immigrants from the west (North Africa), from the north (Anatolia), from the northwest (Mycenae), from the northeast (Armenia and Caucasus), from the east (Mesopotamia and Elam), and from the south (Arabia). The continuity of population in the Levant from the beginning of settled communities in the Neolithic period through the Chalcolithic, Bronze, and Iron Ages cannot be challenged. According to Ernest Tubb, “Small-scale and peaceful infiltrations from beyond the Levantine cultural continuum served only to enrich the culture and not in any way to destroy or replace it.” 6

Prehistory: The Evolution of Humans in the Middle East

The following discussion of human evolution in the Middle East takes place in the context of four geologic periods of the earth’s history. For clarity, these are outlined below.

The Earth’s Four Most Recent Geologic Periods

THE MIOCENE EPOCH (23 million to 5.3 million years ago): Man’s earliest primate ancestors appeared during this period, around 12 million years ago. During the Miocene epoch, dramatic changes in geomorphology, climate, and vegetation took place. It was during this period of volcanic activity and mountain growth that the topography of the modern world was established.

THE PLIOCENE EPOCH (5.3 million to 2.6 million years ago): The earliest hominid species emerged and began walking upright during this period. The climate became cooler and drier, and seasonal. Global average temperatures were 2–3°C higher than today, and global sea levels were 25 meters higher.

THE PLEISTOCENE EPOCH (also called the Great Ice Age; 2.5 million to 12,000 years ago): Hominids begin using tools in this era, around 2 million years ago. During this period, the climate was marked by repeated glacial cycles in which continental glaciers were pushed to as far south as the 40th parallel in some places. It is estimated that 30 percent of Earth was covered by ice. The mean annual temperature at the edge of the ice was 6°C.

THE HOLOCENE EPOCH: The Holocene is the name given to the last 11,700 years of the Earth’s history—the time since the end of the last major glacial epoch, or the Great Ice Age. Since then, there have been small-scale climate shifts—notably the “Little Ice Age” between about 1200 and 1700 CE—but in general, the Holocene has been a relatively warm period.

Periods of Human History: The Stone Age

THE PALEOLITHIC ERA (2 million to 10,000 BCE) is the earliest period of the Stone Age. This era is divided into three periods based on the kind of tools that were used: the Lower Paleolithic (2 million to 200,000 BCE); the Middle Paleolithic (200,000 to 40,000 BCE); and the Upper Paleolithic (40,000 to 10,000 BCE).

THE NEOLITHIC ERA (10,000–4000 BCE) is the last part of the Stone Age. This was the age in which humans began farming and herding animals. The early part of the Neolithic era is called the Natufian, or proto-Neolithic period; it lasted from 12,000 to around 9500 BCE in the Near East. The Pre-Pottery Neolithic, which overlapped the Natufian, lasted from around 10,500 to 6500 BCE; the Late Neolithic, in which distinctive pottery styles characterizing separate cultures emerged, began around 6500 BCE and lasted until the beginning of the Chalcolithic era.

Periods of Human History: The Metal Age

THE CHALCOLITHIC (COPPER) AGE: The Chalcolithic era in the southern Levant lasted some one thousand years (c. 4500–3500 BCE), during which time society saw major changes. Economic change can be seen in the advent of copper metallurgy, the rise of craft specialization, and an increase in long-distance exchange networks.

THE BRONZE AGE: The Bronze Age marks the time when humans began using bronze tools and weapons in place of earlier stone versions. Ancient Sumerians in the Middle East may have been the first people to enter the Bronze Age. Humans made many technological advances during the Bronze Age, including the first writing systems and the invention of the wheel. In the Middle East and parts of Asia, the Bronze Age lasted from roughly 3300 to 1200 BCE, ending with the near-simultaneous collapse of several prominent Bronze Age civilizations.

THE IRON AGE: The final epoch of the three-age division, the Iron Age dates between 1200 and 1000 BCE, or some three thousand years prior to the present. Some scholars maintain that we are still in the Iron Age.

The Earliest Humans in Palestine

Palestine has been inhabited since the Pleistocene epoch. The earliest known remnants of humans in Southwest Asia, fossils of Homo erectus, have been found in Palestine at Ubediya on the southern shore of the Sea of Galilee. These skeletal remains have been dated to about 1.4 million years ago. 7 Finds from the late Acheulian period (middle Paleolithic period, 200,000–40,000 BCE) were discovered in different locations of Palestine ranging from good agricultural lands to desert locations, including the valley of Wadi Araba, south of the Dead Sea, and the high Jordanian plateau. “Archaic” Homo sapiens developed during this period. Modern humans—Homo sapiens—evolved from archaic Homo sapiens, who in turn evolved from Homo erectus (upright man), who lived 2.5 million years ago. 8

About a hundred thousand years ago, Palestine witnessed a gradual but continuous climate shift from largely favorable weather to an increasingly arid climate. These changes, which reached their climax some forty thousand years ago, forced early humans to shift to a lifestyle of settling down around permanent sources of water.

The Neolithic Era

Around thirteen thousand years ago, the inhabitants of Palestine entered what became known as the Natufian era, in which a semi-sedentary lifestyle evolved. The hunters and food gatherers began to establish hamlets and small villages in valleys close to springs where wild grains grew. The term “Natufian” was introduced by Dorothy Garrod, who studied the Shuqba cave in Wadi an-Nutuf near Ramallah and Mugharet el-wad in the Mount Carmel area. The Natufian people lived in settlements that housed a hundred to a hundred fifty people; they were still dependent on hunting, fishing, and food gathering in addition to primitive agricultural activities. There is evidence that they cultivated cereals, specifically rye. Garrod proposed that the Natufian people represented the earliest farmers. 9

The Natufian era was followed by the Neolithic era. Humans lived as hunters and food gatherers until twelve thousand to ten thousand years ago. They lived in small nomadic societies dependent on stationary food sources such as fruits, grains, and tubers beside hunting wild game.

Around 9000 BCE, a dramatic transformation in human life occurred as economic and social changes started to take place. Humans began to establish permanent settlements and moved from hunting and gathering toward a strategy of cultivation and animal domestication. This transformation, which became known as the “Neolithic Revolution,” 10 was an economic and technical milestone as well as a dramatic social and cultural transformation which resulted in major changes in the way humans interacted with one another and with the environment. Sedentary life was instrumental to the growth of civilization. Establishing hamlets and villages required changes in political life, and subsequently the establishment of various forms of government. It also brought the beginning of social stratification, religion, and art.

Palestine was one of the earliest regions in the world to develop sedentary life. Hundreds of villages with five hundred inhabitants or more were established. Some of these villages became towns of several thousand in different regions of Palestine. Among the best-known Palestinian settlements were the oasis town of Jericho (often referred to as the “oldest town in the world”), the town of Beidha near Petra, Ain Ghazal near Amman, and Byblos on the northern coast near modern-day Beirut. Domestication of plants and animals occurred in this period. Grains, particularly wheat, barley, and oats, were the first to be planted and harvested. Meat and milk followed as goats were domesticated. Sheep, pigs, and beef cattle were added to the agricultural economy around 6000 BCE. 11

Between 1952 and 1958, Dame Kathleen Kenyon conducted excavations on behalf of the British School of Archaeology. Near the spring of Ain es-Sultan at the site of present-day Jericho, she found what seemed to be a settlement constructed by Natufian hunter-gatherers of the Mesolithic period that predated the Neolithic Age. Initially they built light shelters, which were eventually replaced by permanent structures built of mud bricks. Around 7000 BCE, Jericho became a well-developed settlement that could be truly described as a town, with massive defensive walls and a stone-built tower. 12

The excavation sites of the South Levant related to the Neolithic Age show special features that distinguish the Palestinian settlers from those of the northern Levant sites. Works of art and plaster statues were found at the southern sites. 13 In 1983, a remarkable discovery was found at the Neolithic site of Ain Ghazal on the outskirts of Amman. Archaeologists unearthed a cache of extraordinary statues modeled in lime plaster over armatures of reeds and twine. These statues were decorated with paint to indicate hair or items of clothing. The facial features were highlighted, and the eyes were built up in a purer white plaster, with a black material used to create the irises and pupils. 14

The transition of human experience from subsisting on wild resources to domesticating both plants and animals was an ongoing subject of research and argument among anthropologists and archeologists. Many theories were introduced to explain the transition toward sedentary life. Most of them emphasized changes in climate as the main factor. The term “Neolithic Revolution” was first introduced by Vere Gordon Childe (1936). His theory of the transition, known as the Oasis-Propinquity Theory, is based on the assumption that “major climatic change at the end of the Pleistocene caused the drying of broad areas, changing them into deserts. Accordingly, plants and animals were dying or becoming scarce. This was true except for desert oases and river valleys. Here, in the only places left with water, humans, animals, and plants clustered and were forced to live in proximity. . . . people soon realized that some animals were more useful than others, so they protected them. They also would have been forced to try new plant foods. By trial and error, they eventually domesticated these, and the Neolithic Revolution was born.” 15

Palestine’s landscape in the Neolithic Age was different from what exists today. The water table was much higher; the Sea of Galilee (Lake Beisan) extended northward to fill the Hula Basin, and filled parts of Beth Shan Valley to the south. The Jezreel and large areas of the central coastal plain were marshland. Between 9000 and 7000 BCE, Palestine enjoyed an extended period of Neolithic prosperity. The mountainous regions of Syria and Lebanon and the high hills of Galilee received abundant rain. Adequate rain was also available in the highland of central and southern Palestine. These climatic conditions allowed Neolithic villages to develop in grassland areas that are now desert. During this period, the agricultural areas in Palestine were greater than ever: they extended in the east to include the Transjordanian plateau, and in the south to include the great plain of Beersheva Basin, Wadi Araba, the northern and central Negev, and the north Sinai highlands. 16

The Stone Age Comes to an End in Palestine

Around 4000 BCE, copper began to be used in the production of metal tools in Syria-Palestine, but it did not displace stone until after 3000 BCE. Copper tools were found in Ugarit in northern Syria, as well as in Tulaylat al-Ghassul north of the Dead Sea. The fourth millennium BCE, in which copper was used by these advanced communities, is called the Chalcolithic Age (the name is derived from the Greek word for copper).

Excavations conducted at the site of Tulaylat al-Ghassul, situated east of the River Jordan and close to the end of the Dead Sea, revealed a large open settlement of well-constructed rectangular mud-brick houses covering some sixty acres. In addition, this settlement had two cultic centers contained within a walled enclosure. A cultic area was also found at Ein Gedi, a spring-fed oasis on the western shore of the Dead Sea. This settlement also featured a large stone installation that appears to be an altar, as it was filled with ashes from burnt offerings. Evidence of metalworking was found at these two sites, as well as at Abu Matar in the Beersheba area. An extraordinary hoard of copper objects was found in the caves of Nahal Mishmar in the hills to the west of the Dead Sea. 17 Traces of Chalcolithic culture have been found in several other sites in Palestine, such as Jericho, Megiddo, Beth-shan, Lachish, and Byblos. In the Chalcolithic Age, as in the Neolithic period, inhabitants of Syria-Palestine were ahead of the rest of the Near East.

Climatic Changes Set the Stage for Palestine’s Mediterranean Economy

Between 9000 and 7000 BCE, North Africa, between the Nile in the east and Gibraltar in the west, also experienced a prosperous Neolithic period. Neolithic farmers settled in small villages along the many valleys of the coastal region. They were dependent on farming as well as on hunting and herding of pigs, beef cattle, sheep, and goats. Their main agricultural products were wheat and barley. 18

Throughout the seventh millennium BCE, significant climate changes occurred in the entire Mediterranean basin. Sea levels fell steadily, as did the water table in most regions, especially east and south of the Mediterranean. Higher temperatures and longer dry summers dominated the climate. In North Africa, these changes continued throughout an extended periods of droughts that lasted for over a thousand years and resulted in the creation of the Great Sahara of North Africa. This drastic climate change and its effect on agriculture forced farmers and herders to move westward to the Berber lands and southward to Chad and the Darfur region. Many more moved eastward to the central Nile Valley. 19

The entire ancient Near East was affected by this change in climate. The Sinai Peninsula changed from steppeland to desert. Arabia, apart from the southern corner of the peninsula (Arabia Felix), became a vast expanse of desert. On the other hand, the delta marshlands of Tigris and Euphrates valleys dried up and turned into rich agricultural lands which became the heartland of ancient Sumer, the oldest ancient Near Eastern civilization. In Egypt, the climate change resulted in the draining of the Nile Delta, creating fertile agricultural land. Dense settlements occupied the banks of the Nile from Asut in the south to the delta in the north. These changes in the delta opened up the migration route for the refugees of North Africa to move through Sinai to Palestine. Sometime between 4500 and 4000 BCE, the expanding desert closed the migration route toward the delta and the Fertile Crescent. 20 In Palestine, the drought resulted in the retreat of the shores of Lake Beisan to what became the Sea of Galilee and Lake Hula. The dried-up swamps and marshlands in the central lowland valleys of Palestine and Syria became rich farmlands. 21

Over a period of nearly two millennia, refugees from North Africa crossed the Nile and moved northward into Sinai, Palestine, Syria, and Arabia, where they gradually merged with the indigenous farmers and shepherds. By the early third millennium, some immigrants had moved into Mesopotamia and merged and integrated with the ancient Sumerians. Others moved from Transjordan and entered Arabia.

The early waves of refugees from North Africa to Palestine and Syria led a pastoral and nomadic life. Some of the refugees settled in previously uninhabited regions. The majority settled in the inhabited regions side by side with the indigenous population, affecting their cultures, languages, religions, and arts. By the fifth millennium BCE, the new immigrants had joined the already established populations in the northern coastal regions of Phoenicia and the Carmel range, in the southern Jordan Valley, in northern Transjordan, and the southern coastal plains. Over a long period of time—almost a thousand years—they were gradually assimilated by the indigenous population of the early Neolithic villages who had survived the drought. The natives and the newcomers formed a new population, a new culture, and distinctive new languages and dialects that became West Semitic.

The dry period that lasted between the seventh and fifth millennia was followed by a “sub-pluvial” period characterized by lower temperatures and excess rainfall. This change in climate made farming and herding possible in many places in Palestine and Syria. By the end of the fourth millennium, farming had become a permanent feature of Palestine’s landscape. These changes in climate created a major shift in settlement patterns. The bulk of the population was concentrated in regionally dominant towns whose surrounding fields had good soils and springs, such as Megiddo, Beth Shan, and Acco in the northern lowlands; Ashqelon and Gaza in the southern lowlands; and Hazor (Tel al-Qadeh), Shechem (modern-day Nablus), Jerusalem, Lachish, and Gezer in the highlands. 22

Once the great drought ended, the newly integrated population in Palestine and Syria began to build a stable economy that was balanced between three different specializations: grain cultivation in the plains and valleys, horticulture and viniculture focused on the production of olives and wine in the highland areas, and sheep-and goat-herding in the grassy steppelands. Other economic specializations of considerable importance existed, such as date cultivation in desert oases, metalworking in the Araba and Negev, salt harvesting on the Phoenician coast, taking tar from the Dead Sea, timber harvesting in the highlands, and fishing in the Sea of Galilee. Trade was the backbone of this integrated economy, which became known as the Mediterranean economy. Trade necessitated constant interaction between different groups and forced interdependence in all aspects of the economy. Grapevines and olive trees were first cultivated and fully domesticated in the eastern end of the Mediterranean (Palestine), and through trade and colonization they spread through the entire Mediterranean basin.

The survival and expansion of the economy depended on communication between the different villages and on the interchange of goods between regions. This form of economy, which was dependent on the flow of goods between regions, also opened Palestine to the outside and brought it under the influence and control of more powerful neighbors.

This unique form of agriculture, the Mediterranean economy, was to determine the basic structure of Palestine’s economy and much of its history for more than five thousand years. Palestinian agriculture pioneered the development of a type of farming that has become the hallmark of the Mediterranean world. Its centre is trade. Rather than a subsistence agriculture, which involves trade only as a result of tentative and slow development of surpluses, or through an exploitation by more powerful neighbors, Palestine’s economy was oriented from its beginning toward the barter and exchange of basic trade goods. . . . These were not surpluses but the fundamentals of the economy. 23

The Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is the period during which tools and weapons were made primarily from bronze. In the Near East, this period extended between 3300 and 1150 BCE. Bronze is an alloy consisting of 85 to 95 percent copper, with the remainder consisting of tin or arsenic. Bronze melts at 950°C, so it is easier to cast than copper, which melts at 1084°C. Both copper and bronze make strong, hard tools and weapons. The Bronze Age is divided into three periods based on changes in pottery style:

- Early Bronze (EB) (3300–2000 BCE)

- Middle Bronze (MB) (2000–1550 BCE)

- Late Bronze (LB) (1550–1150 BCE)

Palestine in the Early Bronze Period: The Rise of Urbanism (3300–2400 BCE)

The third millennium BCE witnessed the establishment of the urban civilizations of Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia. Consequently, a more elaborate and complex system of trade routes was developed which stimulated the Palestinian economy and led to similar urban development in Palestine. As mentioned above, farming in Palestine matured during the fourth millennium to meet the needs of trade. It evolved into what became known as the Mediterranean economy, centered on trade rather than a subsistence agriculture.

During the early Bronze Age, agricultural settlements were established in fertile valleys and plains. These settlements ranged in size from a single family or a few families to towns of a few thousand. Palestine was a land of small farmers, a heartland of villages. Farming and village life were determined by the availability of water. Wherever sufficient water was available to support its population through arid summers, and wherever rich soil was available, a village was established. Lands where water was plentiful, such as the Jezreel Valley and the coastal plains of both northern and southern Palestine, had the largest number of agricultural settlements. Palestinian farmers developed simple systems of canals and irrigation ditches in the marshlands of the Beth Shan and Jezreel valleys. In the hill country, dry farming techniques and methods for storing water for human and animal consumption were utilized. At Arad, a large artificial reservoir was constructed in order to collect runoff rainwater. The vast bulk of the population—estimated at about 90 percent—was engaged in farming and herding. The remainder were metalworkers, woodsmen, hunters, or traders. The agriculture of Palestine was regionally differentiated, with one area growing wheat, another investing in olives or grapes, and another committed to livestock. The economy was driven by the production of export goods. The villagers produced cash crops: wool, flax, meat, cheese, grains, nuts, fruits, olive oil, wine, timber, pottery, salt, leather, flint tools, copper and turquoise. Olives, which served as a main food crop and the primary source of oil for lamps, were the most valuable commodity. These cash crops linked Palestine with Egypt, Phoenicia, Syria and Mesopotamia. 24

As a result of greater rainfall during the early Bronze Age, the Sinai and the central and southern Negev developed into a grassland contiguous with the Great Syrian Steppe to the north. A significant population of pastoralists developed over a large area that included the whole of the eastern and southern Levant. The lower slopes of the hills and the adjacent valleys provided suitable areas for planting wheat and barley. Turquoise, copper, natron, and bitumen industries along the shores of the Dead Sea, southern Araba, and central Sinai provided supplementary occupations for the expanded population of this region.

The early Bronze Age saw the development of strong defensive systems. At Jericho, the town wall was built of mud bricks on stone foundations, and was initially a meter thick. By the end of the early Bronze Age, its thickness had increased to five meters. At Arad, the settlement was protected by a substantial stone-built wall supplemented at regular intervals with semicircular bastions. Excavations have revealed evidence of town planning at several sites. Within the town walls, well-constructed houses built either of stone or mud bricks on stone foundations were laid out on a grid of intersecting streets. The residences were separate from the public buildings, which included a palace, administrative buildings, and temples. 25

Palestine was fully urbanized during the early Bronze Age. The material culture of Palestine during this period displays a high level of technical accomplishment. Excavations have revealed advanced and elegant pottery work, including jugs, juglets, bowls, cups, platters, jars of different shapes and sizes, and cooking pots. Many of the vessels are decorated with highly burnished red or brownish-purple painted designs.

Similar advances in metal technology have been revealed. Burial customs are another indicator of the social and cultural advancement of Palestinian society: grave goods were placed inside the tombs for the afterlife. 26

Geographically, Palestine’s regions were diverse and physically isolated from each other. The largest population centers were considered small market towns rather than cities. Politically, Palestine was made up of independent towns and villages, each ruled by an autonomous patron. The power of the patrons was based on their character and personal commitment to their small communities. The small autonomous communities were able to protect and maintain their independence by building strong fortifications and establishing alliances with other towns. Although they were competing, they realized the need for cooperation for the benefit of trade and protection. The populations of these communities were just a few thousand each, which prevented the establishment of a regional statehood. Although historians refer to these communities of the early Bronze Age as “city-states,” none of these hamlets, villages or towns were in the same category as city-states like Nineveh or Babylon, which were great cities with at least a quarter of a million inhabitants. In most cases, local authorities were able to provide support and protection for local and inter-regional trade; however, they were unable to keep commerce secure over great distances.

Major trade routes in the Near East began to develop during the early Bronze Age, reaching their maturity by 1500 BCE, when Egypt dominated all of Palestine. Long-distance trade was dependent on the great powers and states of the Fertile Crescent: Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia. The neighboring states, especially Egypt, controlled international trade along the Mediterranean coast and throughout Palestine’s lowlands. The overland international trade routes linking the Nile Valley with Syria, Anatolia, and Mesopotamia passed through Sinai and used Palestine as a land bridge. The sea routes utilized the Phoenician ports.

During the early Bronze Age, Egypt dominated Palestine politically and economically, but not to the point of turning it into a province. Egypt formed the main market for Palestine’s produce. Commodities such as wine and olive oil were in great demand in Egypt. Canaanite jugs have been found in many of the Egyptian tombs of the first dynasty at Abydos. Excavations at Tell es-Sa’idiyeh—situated in the central Jordan Valley, about 1.5 kilometers east of the River Jordan, on the south side of one of its tributaries, Wadi Kufrinjeh—uncovered evidence of industrial-scale production of olive oil, wine, and textiles.

In conclusion, the geographically fragmented Palestinian society of the early Bronze Age succeeded in developing its “Mediterranean economy” due to the following elements:

- Specialized food production between the different regions of Palestine according to the topography of the land and the availability of water resources.

- Special relationships between the different regions based on cooperation and coordination between the different regions.

- Inter-regional and international trade.

Economic Recession: The End of the Early Bronze Age (2400–2000 BCE)

Around 2400 BCE, Palestine’s urban culture started to decline, resulting in a severe economic recession that lasted until the end of 2000 BCE. The decline of the urban civilization in Palestine during this period was the result of a long period of devastating drought. The unprecedented population growth in the third millennium was beyond the country’s capacity, especially as there were no stable sources of water. Unlike Egypt and Mesopotamia, Palestine was dependent on rainfall, not on great flowing rivers. The densely populated agricultural regions, devastated, were diminished significantly. Farmers were forced into nomadic lifestyles. Patch agriculture and sheep-and goat-herding increased.

The northern population living in the fertile zones of the agricultural heartlands of Palestine survived the drought and continued as farmers. In the south, in the central Negev highlands, Sinai, and the Transjordan Plateau, people turned to herding and spread in small groups, creating hundreds of small hamlets and villages. Pastoral nomadism and patch agriculture became distinctive ways of life throughout the steppe regions of Palestine. “Many families were forced out of greater Palestine altogether . . . [and] emigrated northeastward into the highlands of Jebel Bishri of the Great Syrian Steppes. Yet others emigrated into the oases of the Arabian desert, destined to return to the fringes of Palestine a thousand years later as Arabs.” 27 Many of the inhabitants of the Negev moved to the Sinai mines and to the eastern Nile Delta. These changes in Palestinian society did not happen suddenly; rather, it was a gradual transformation. The population of Palestine as a whole was diminished significantly, and the people who remained were concentrated in the richest and largest agricultural zones.

As mentioned earlier, urbanism in Palestine during the early Bronze Age was related to the establishment of urban civilization in Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia. The drought of the twenty-fourth century BCE affected the entire Near East, causing civil unrest and political conflict in the entire region, including Egypt and the city-states of southern Mesopotamia. Toward the end of the third millennium, the Old Kingdom in Egypt collapsed, leading to a total cessation of trade links. The shrinking of trade and commercial activities with Egypt was another negative factor that contributed to the economic recession in Palestine, especially in the central and southern regions, where there was a significant decline in urban life. The situation in northern Palestine was slightly different, as the factors contributing to the decline in urban life were offset by other circumstances. The northern towns maintained and even increased trading activities with inland Syria during EB IV (2400–2000 BCE). Economic texts from Ebla, just south of Aleppo, contain evidence of such ties. Excavations at several sites in northern Palestine unearthed a large number of imported Syrian products. Hazor (Tel al-Qadeh), Megiddo, and Beth Shan witnessed a shorter period of economic recession instead of a collapse of urban life. 28

The pottery of this period lacks the elaborate and delicate luxury vessels seen earlier in the Bronze Age, consisting of more functional and multi-purpose pieces. It is also characterized by the disappearance of the commercial storage jar, as there was no market for bulk commodities. This does not mean technical regression occurred. As a matter of fact, excavations at several sites demonstrate evidence of development of new advanced techniques, especially at sites that underwent extensive and more permanent occupation. “The pottery of Tiwal esh-Sharqi [on the south bank of the River Zarqa, close to the Jordan River] was superbly made: the clays well prepared, the firing even and carefully controlled and the skillful use of the fast wheel producing wonderfully thin-walled vessels.” 29 Metalwork also showed similar technological advances. Improved casting techniques produced one of the most characteristic weapon types of this era, the “fenestrated axe” (an axeblade with holes in it).

The end of the early Bronze Age marks a temporary setback in the developmental process of the urban civilization of Palestine. The climate changes that created the economic recession did not destroy the urban civilization completely; Palestinian society adapted to the new economic situation and established a balance between urbanism and agriculture on the one hand and semi-sedentism and pastoralism on the other.

The spectrum of sedentarization from farmers living in towns to shepherds living in forms of seasonal nomadism is related to different ways of making a living. In Palestine, such differences are created by recurring efforts to adapt to changes in the climate and the environment. The dominance of one form over another is due to the effects of trade, on which the whole of Palestine’s Mediterranean economy was dependent. The population as a whole was stable only to the extent that it was flexible. It used many forms of both nomadism and settlements, depending on the needs of the region in which they were found and on the temporary changes in weather and economy. 30

Palestine witnessed several cycles of economic depression and destabilization of its agriculture, as well as periods of prosperity and sedentism. The economic depression at the end of the early Bronze Age shifted the economy toward pastoralism and grain agriculture, which resulted in population movement into hundreds of small hamlets in the steppeland of central Negev and Sinai and the Transjordan Plateau. When the drought ended, some of those who had turned to pastoralism did not return to agriculture, as there was a need to specialize in pastoralism to meet the demands of the market. The middle of the early Bronze Age and the middle of the mid Bronze Age were known as periods of relative affluence, population growth, and political concentration compared to the end of the early Bronze and the beginning of the late Bronze Age, which are described as periods of economic collapse.

In conclusion, the urban civilization of Palestine underwent a developmental process that started in the later part of the fourth millennium BCE, during which the agricultural economy matured and the Palestinians established their Mediterranean economy. Urbanism in Palestine made great progress during the early Bronze Age, between 3300 and 2400 BCE. The EB IV period between 2400 and 2000 BCE represents a temporary setback in this developmental process. It is fair to describe this period as an economic recession rather than a collapse of urbanism. The cultural changes during this period were the result of indigenous changes in lifestyle in response to economic changes. This process occurred slowly and gradually. At the beginning of the recession, the EB II and EB III elements were dominant, but as the recession became fiercer and more deeply rooted, the EB IV element took over and grew in prominence. The reversion to urbanism during the middle Bronze Age became possible with the reversal of the factors that had contributed to the decline of urbanism. 31

Palestine During the Early Second Phase of the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1750 BCE)

When the drought ended around 2000 BCE, sedentism and intensive agriculture returned to the heartland of Palestine. Throughout Palestine more settlements were built, even in the southern hills and the coastal plain that had been abandoned during the drought. The return of a wetter, cooler climate brought economic prosperity as new agricultural areas were developed. Significant differences existed between the north and the south, however. The densely populated north began to develop an economy and culture that were more prosperous and independent than those of the south. The annual precipitation in the north was nearly three times that of the south. Palestine’s northern regions had a greater potential for producing wine, olive oil, and grains than the southern regions. They were also able to maintain a much longer period of stability. 32

The beginning of the middle Bronze Age in Palestine coincides with the beginning of the Middle Kingdom in Egypt. Around the end of the third millennium BCE, Mentuhotep II, the founder of the Middle Kingdom (2055–2010 BCE), reestablished a central administration in Egypt, which restored political and economic stability to that nation, and reopened the trade routes in Palestine.

The social and economic changes during the middle Bronze Age led to a revitalization of urban life and a shift in the equilibrium toward sedentism and urbanism. The material culture of the initial phase of the middle Bronze Age (2000–1750 BCE) combined the advanced production methods of the end of the early Bronze Age and the older, dormant methods used prior. The vessels of this period were the most beautiful ever produced in Palestine. Advanced techniques were applied in the production of luxury jugs, bowls, and pitchers. The return of the trade routes necessitated the production of new commercial storage jars suitable for transportation. 33

Palestine during the Late Second Phase of the Middle Bronze Age (1750–1550 BCE)

The late second phase of the middle Bronze Age coincides with the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt. This period is considered to be the golden age of the Canaanite culture; during this time, Palestine had strong diplomatic and commercial relations with the Delta pharaohs in Avaris.

Canaanite culture flourished unrestrained. Architecture, art and craftsmanship achieved levels of accomplishment and sophistication which were to provide the ancient Near East with an enduring legacy well into the following millennium. The hoard of gold jewellery found at the site of Tell el-Ajjul, for example, well illustrates the high level of expertise and skill of the Canaanite craftsman [in jewelry, ivory carving, and wooden furniture] . . . The essence of Canaanite art is its eclecticism, drawing elements from a variety of sources and countries, and blending them together to form a totally coherent, aesthetically satisfying whole. . . . [They] were laying the foundations for the Phoenicians, their direct descendants, whose artistic traditions were to enrich so greatly the Near Eastern cultures of the first millennium BCE. 34

The progress of Canaanite art of the middle Bronze Age was the result of extensive commercial relations with Egypt, Syria, Anatolia, and Cyprus.

During the third millennium BCE, the Semitic language of the Canaanites was written in the cuneiform Mesopotamian system of writing founded by the Sumerians. This cumbersome system continued to be used throughout most of the ancient Near East until the beginning of the second millennium BCE, when it was replaced by an alphabetic system developed by the Canaanites. The invention of alphabetic writing is seen as the most valuable achievement of the Canaanites. The Phoenicians refined this system and transmitted it to the rest of the world in the first millennium.

During the middle Bronze Age, the Palestinians began to show interest in temples and shrines. Excavations at Nahariyah revealed a Canaanite temple made of a simple structure in the form of a rectangular room with the entrance in the middle of the long wall. The altar was located south of the building on a large stone-built raised platform. A large number of animal bones were found in that location, along with pottery vessels and female figurines. It is believed that a female deity, possibly Astarte, was being worshipped there. Excavations at Shechem (modern-day Nablus), Tell el-Hayyat, Hazor (Tel al-Qadeh), and Megiddo show evidence of a distinctive new type of temple. This was still rectangular, but the entrance was located in one of the short walls surrounded by square towers. It was a long-room temple, unlike the older broad-room style. The new structure was characterized by its thick walls; hence it was called migdol, which means fortress.

The political structure in Palestine during this part of the Bronze Age was characterized by the establishment of large independent urban centers composed of a number of towns and villages that were controlled by a major city. This became known as the period of Canaanite city-states. From time to time, groups of city-states formed loose confederations for the purpose of gaining a better position in the competitive market, as well as for protection. Elaborate systems of fortification were established around each of the major cities. 35

The resilience of early Palestinians to withstand the changes brought by drought in the early Bronze Age laid the foundation for a rise in urbanism characterized by Canaanite refinement of language necessary for a trade-based economy. The culture of Bronze-Age Palestine was shaped by influences from Egypt, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. In the next chapter, we will explore those influences in greater detail.