Islam: The Message and the Messenger (Unabridged)

الرساله و الرسول

Mecca: The Consecrated City

The Biblical story of Abraham states that he migrated from Ur in Southern Mesopotamia to Haran, on one of the upper Euphrates tributaries, in northern Syria. In Haran, God appeared to him and commanded: “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great so that you will be blessing” (Genesis 12:1–2). This land was Palestine. The myth dates this event to the second millennium BCE.

The myth also states that Sarah gave Abraham her Egyptian slave, Hagar, to be his concubine in hopes that God might give him a child through her, as Sara could not produce children because of her advanced age. Hagar gave birth to a child named Ismael. Abraham’s joy was great. As Sarah watched Hagar looking after her newborn son, Ismael, her jealousy grew stronger every day, especially when she noticed that Abraham was showing great love to Hagar and Ismael.

The second chapter takes place far away from Palestine. Sarah requested that Abraham send Hagar and Ismael away. Abraham traveled with Hagar and Ismael from Hebron in south Palestine to a desolate valley in the Arabian Peninsula which came to be known as Mecca—a forty-day trip by camel. Abraham left Hagar and her son in that uninhabited place, with little food—mainly dates—and a small amount of water, and went back to Palestine where he had left Sarah. He was sorry to leave them in the desert; however, he believed that God himself had guided him to that place. As he left, Hagar shouted to him: Are you abandoning us here on God’s order? When his answer was affirmative, she said: “He who has ordered you to do that will not abandon us.”

On his way back to Palestine, Abraham was still concerned about the fate of the family that he had abandoned. He stopped to pray, addressing his God:

Our Lord, I have settled some of my offspring in a valley where there is no vegetation, by Your Sacred House, our Lord, so that they may perform the prayers. So make the hearts of some people incline towards them, and provide them with fruits, that they may be thankful.

(Chapter 13, Ibrahim)

رَّبَّنَا إِنِ ي أَسْكَن ت مِن ذ ِ ريَّتِي بِوَا د غَيْرِ ذِي زَرْع عِندَ بَيْتِكَ الْ محَرَّمِ رَبَّنَا لِي قِي موا الصَّلَةََ فَاجْعَلْ أَفْئِدَة ِ منَ النَّاسِ تَهْوِي إِلَيْهِمْ وَارْ زقْ هم ِ منَ الثَّمَرَاتِ لَعَلَّ همْ يَشْ ك رونَ(37)

سورة إبراهيم )13(

Hagar devoted herself to her young child. For a few days she and her son survived on the dates and water Abraham had left. Soon, however, her supply of food and water was exhausted. The two were soon very hungry and thirsty. She was in a valley between two hills: al-Safa and al-Marwah المروى و الصفى. She kept running between the two hills exploring the area around her, hoping to find somebody to help. When she had run between the two hills seven times, she heard a voice very close to her, but she could not see anyone. It asked her who she was. She answered, “I am Hagar, the mother of Abraham’s son.” The voice asked her, “To whom has he entrusted you in this barren place?” She replied: “He entrusted us to the care of God.” The angel rejoined: “He has then trusted you to the All-Merciful, the Compassionate.” During this time, the boy, Ismael, was in the bottom of the valley between the two hills, rubbing the earth with his foot.

As she finished the conversation with the angel, and while the boy was rubbing his foot against the earth, water gushed forth between his feet. Hagar shouted, “God is Supreme.” She rushed back to her son. After giving her child enough to drink, she drank herself and thanked God for His grace. The water continued to gush forth and attracted birds. An Arabian tribe called the Jurhum was traveling north across the desert when they saw a bird flying nearby. They realized that a spring must be in the area. They moved toward the spring to wash and drink. They then met Hagar and realized that the spring belonged to her. She welcomed the Jurhum tribe and invited them to encamp. They liked the place, and Hagar was very happy to have them settle down in the area. This was the beginning of settled life in the valley of Mecca. Ismael grew up among the Jurhum tribe, and when he became a young man he married a Jurhum girl who gave him many sons and daughters. In effect he became one of the Jurhum tribe.

Abraham visited Hagar and Ismael every now and then. On one of his visits, Abraham saw in his dream that he was commanded to sacrifice his son, Ismael, for God’s sake. Ismael, who was in his teens at that time, did not deny his father:

Then, when he was old enough to accompany him, he said, “O my son, I see in a dream that I am sacrificing you; see what you think.” He said, “O my Father, do as you are commanded; you will find me, Allah willing, one of the steadfast.”

(Chapter 23, as-Saffat)

فَلَمَّا بَلَغَ مَعَه السَّعْيَ قَالَ يَا ب نَيَّ إِنِ ي أَرَ ى فِي الْمَنَامِ أَنِ ي أَذْبَ حكَ فَان ظرْ مَاذَا تَرَ ى ۚ قَالَ يَا أَبَتِ افْعَلْ مَا ت ؤْمَ ر ۖ سَتَجِ دنِي إِن شَاءَ اَّللّ مِنَ الصَّابِرِينَ (102)

(سورة الصافات (23

Abraham and Ismael went to a place that became known as Mina منى and prepared to obey God’s orders. Satan tried to dissuade Abraham from sacrificing his son. Abraham’s submission to God’s will was firm, so he stoned Satan in three different spots. Just at the point when Abraham was about to cut his son’s throat, an angel appeared and told him to stop.

When they had both submitted to God, and he had laid his son down on the side, We called out to him, “O, Abraham! You have fulfilled the vision.” Thus We reward the doers of good. This was certainly an evident test. And We redeemed him with a great sacrifice. And We let him be praised by later generations. Peace to be upon Abraham. Thus We reward the doers of good. He was one of Our believing servants.

(Chapter 23, as-Saffat)

فَلَمَّا أَسْلَمَا وَتَلَّه لِلْجَبِينِ (103) وَنَادَيْنَاه أَن يَا إِبْرَاهِي م (104) قَدْ صَدَّقْتَ الرُّؤْيَا ۚ إِنَّا كَ ذَلِكَ نَجْزِي

الْ محْسِنِينَ (105) إِنَّ هَذَا لَ هوَ الْبَلََ ء الْ مبِي ن (106) وَفَدَيْنَاه بِذِبْح عَظِي م (107) وَتَرَكْنَا عَلَيْهِ فِي

الْخِْرِينَ (108) سَلََ م عَلَ ى إِبْرَاهِيمَ (109) كَذَلِكَ نَجْزِي الْ محْسِنِينَ (110) إِنَّه مِنْ عِبَادِنَا الْ مؤْمِنِينَ (111) )سورة الصافات )23

On another visit, Abraham told his son that God had ordered him to erect a house in that place to serve as a consecrated temple. Both father and son worked hard to lay the foundations and erect the building. As they completed the building, they prayed and asked God to accept their work and bless their seed. The Quran quotes their prayer:

As Abraham raises the foundations of the House, together with Ishmael, “Our Lord, accept it from us. You are the Hearer, the Knower. Our Lord, and make us submissive to You, from our descendants a community submissive to You. And show us our rites, and accept our repentance. You are the Acceptor of Repentance, the Merciful. Our Lord, and raise up among them a messenger, of themselves, who will recite to them Your revelations, and teach them the Book and wisdom, and purify them. You are the Almighty, the Wise.”

(Chapter 1, al-Baqara)

رَبَّنَا وَاجْعَلْنَا مسْلِمَيْنِ لَكَ وَمِن ِ ذريَّتِنَا أ مَّة مُّسْلِمَة لَّكَ وَأَرِنَا مَنَاسِكَنَا وَت بْ عَلَيْنَا ۖ إِنَّكَ أَنتَ التَّوَّا ب ربنا

رَبَّنَا وَابْعَثْ فِيهِمْ رَ سو ل ِ منْ همْ يَتْل و عَلَيْهِمْ آيَاتِكَ وَي عَلِ م ه م الْكِتَابَ وَالْحِكْمَةَ وَي زَ ِ كيهِمْ ۚ إِنَّكَ أَنتَ (128) الرَّحِي م الْعَزِي ز الْحَكِي م)129(

سورة البقرة )1(

We showed Abraham the location of the house: “Do not associate anything with Me, and purify My House for those who circle around, and those who stand to pray, and those who kneel and pray.” And announce the pilgrimage to humanity. They will come to you on foot and on every transport. They will come from every distant point. That they may witness the benefits for themselves, and celebrate the name of Allah during the appointed days, for providing them with the animal livestock. So eat from it, and feed the unfortunate poor. Then let them perform their acts of cleansing, and fulfill their vows, and circle around the Ancient House.

(Chapter 17, al-Hajj)

وَإِذْ بَوَّأْنَا لِِبِْرَاهِيمَ مَكَانَ الْبَيْتِ أَن لَّ ت شْرِكْ بِي شَيْئ ا وَطَ ِ هرْ بَيْتِيَ لِلطَّائِفِينَ وَالْقَائِمِينَ وَالرُّكَّعِ السُّ جودِ (26)وَأَذِ ن فِي النَّاسِ بِالْحَ جِ يَأْت وكَ رِجَا ل وَعَلَ ى ك ِ ل ضَامِ ر يَأْتِينَ مِن ك ِ ل فَ ج عَمِي ق (27) لِ يَشْهَ دوا مَنَافِعَ لَ همْ وَيَذْ ك روا اسْمَ اَّللِّ فِي أَيَّا م مَّعْل ومَا ت عَلَ ى مَا رَزَقَ هم ِ من بَهِيمَةِ الْنَْْعَامِ ۖ فَ كل وا مِنْهَا وَأَطْعِ موا الْبَائِسَ

الْفَقِيرَ (28) ث مَّ لْيَقْ ضوا تَفَثَ همْ وَلْي وف وا ن ذ ورَه مْ وَلْيَطَّوَّف وا بِالْبَيْتِ الْعَتِيقِ (29)

سورة الحج )17(

God accepted the work done by Abraham and Ismael and answered their prayers. He made the building they erected into a center of worship to which people from all over the world came on pilgrimage. God told Abraham that it was his will that Mecca should be a consecrated city where fighting was forbidden. Its animals were to move about safely without fear of being hunted. It was forbidden to cut down its trees. People were secure and safe there. Such has been the status in Mecca ever since Abraham built that house which was the first House of God ever built.

The pagan Arabs believed that this sanctuary, the Ka’bah, was built first by Adam, the first man. They also believed that Adam’s original building was destroyed by the Great Flood, then rebuilt by Noah. They also believed that after Noah, it was forgotten for generations until Abraham rediscovered it while visiting Hagar and Ismael. The truth is that no one knows who built the Ka’bah, or when it was built. Most likely the discovery of Zamzam زمزم in the middle of the desert by the wandering Bedouin tribes of Arabia was the reason for the sanctity of the area. It is likely, then, that the Ka’bah الكعبه was erected in that valley not just as a sacred place, but as a secure place to store the consecrated objects used in the rituals that had evolved around Zamzam.

The Quraysh, Custodians of the Ka’bah

The Jurhum tribe was the first to settle in Mecca. In time, other tribes came and settled there. The Jurhum, who were considered the “maternal uncles of Ismael,” became the custodians of the Ka’bah. As such, the Jurhum were the leaders of Mecca. They continued to hold their position as custodians of the Ka’bah for a long time. However, as time passed, they abused their position, which resulted in them losing the honor of the custody of the Ka’bah to another tribe, the Khusa’ah خزاعه. The Jurhum did not surrender willingly. As they left Mecca, they collected all the treasures of the Ka’bah, buried them in the well of Zamzam, leveled the well, and removed all traces of its location.

The Khusa’ah tribe held the custodianship of the Ka’bah and the leadership of Mecca for a long time, until the Quraysh tribe, under the leadership of Qusayy ibn Kila’b, took over. Qusayy was the fifth grandfather of the Prophet, Muhammad bin Abdulla’h. Qusayy, who was an intelligent, honorable young man of the Quraysh, married the daughter of the Khusa’ah chief Hulayl ibn Hubshiyyah. Hulayl recognized the qualities of leadership in Qusayy and was very fond of him. On his deathbed, Hulayl made it known that Qusayy was his choice as custodian of the Ka’bah and ruler of Mecca.

After settling disputes with his rivals, Qusayy asked all the clans of Quraysh to join him in his effort to organize the city. He earned the support and respect from all the clans of his tribe. He built a big hall next to Ka’bah to serve as a meeting place for the Quraysh and called it Dar al-Nadwah الندوة دار. In this building he gathered representatives of all clans for consultations. He also established the tradition of Rifadah الرفادة where he offered the pilgrims food they needed when they arrived in the city. He gathered the Quraysh notables and set the rules of al-Rifadah: “The pilgrims when they visit God’s House are God’s guests. You must be hospitable to them. Let us then provide them with food and drinks in the days of pilgrimage until they have left our city to return to their homes and families.”

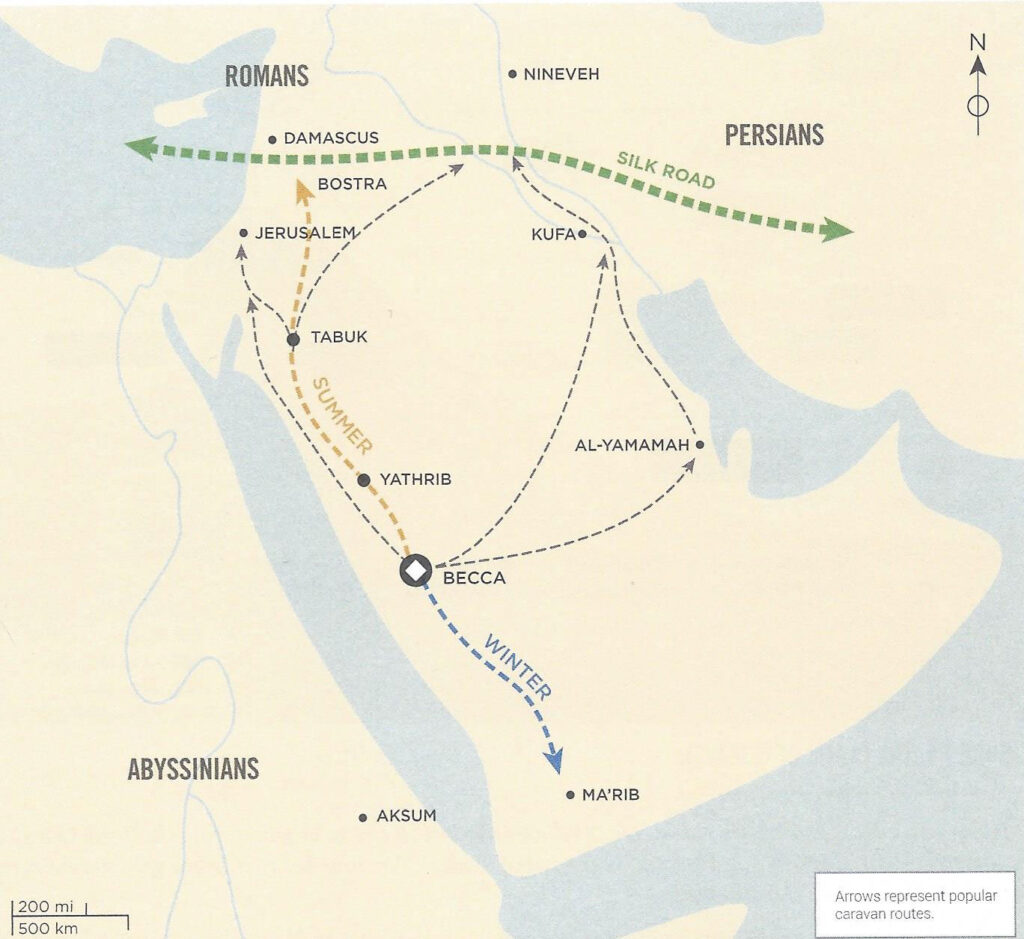

Qusayy was succeeded by a number of leaders from his offspring who continued the same traditions of looking after the tribe and taking care of the pilgrims. Hasidim, Qusayy’s grandson, put hospitality to pilgrims on an unprecedented level. He provided all the funds needed for Rifadah from his own wealth, which came from trade. He was interested in offering his commercial expertise to all members of his tribe so that he could enhance the wealth of the entire community. He started the biannual commercial trips: in the summer a large commercial caravan went from Mecca to Syria, and a similar one went to Yemen in winter. Each caravan was a joint enterprise in which all Meccan people shared. It brought profit to the people and prosperity to the city.

One of the most prominent successors of Hashim was his son Abd al-Muttalib, who continued the tradition of Rifadah. However, he faced the problem of the water shortage in Mecca. There were only few scattered wells, which hardly were sufficient for the needs of the population. One night he dreamed a voice was telling him to “dig the good one.” This dream was repeated for several nights. In his dream, Abd al-Muttalib asked the voice, “What is the good, blessed one?” For the first several nights he did not get an answer. At last, one night the voice answered: “Dig Zamzam.” The following morning Abd al-Muttalib started digging between al- Safa and al-Marwah. He dug for three days until his shovel hit something metallic. When he removed the sand around the metallic object, he discovered two gold deer and other valuables, including a large quantity of shields and swords. He recognized that these were the objects that the Jurhum had buried in Zamzam when they left Mecca. He continued digging, and soon he found the well. He shouted: “God is supreme. This is indeed Ismael’s well. This is Zamzam, the drinking water of pilgrims.” Abd al-Muttalib and his offspring dedicated the well for the benefit of the pilgrims and continued to provide them with all the water they needed.

Social and Economic Life in Arabia before Islam

During the sixth century CE, nomadic life (badawah البداوة) was the rule in northern Arabia. Settled life in the steppes was almost impossible, due to the scarcity of resources. Nomads relied on herding sheep and goats, and breeding horses and camels, for their existence. Nomadic life was harsh, characterized by constant struggle, because there were too many people competing for too few resources. They were constantly wandering in search of water and grazing land for cattle. Always hungry, on the brink of starvation, they fought with other tribes for water, pastureland, and grazing rights. Consequently the gazu الغزو (acquisition raid) was essential to the badawah economy. In times of scarcity, tribesmen would invade the territory of their neighbors for the purpose of stealing camels, cattle, or other valuables; however, they avoided killing anybody. The gazu was not considered a crime or morally wrong; it was a rough means of redistributing wealth when there was not enough to satisfy the needs for survival.

The tribe was the basic unit of social life in nomadic Arabia; and the tribal society was governed by a traditional tribal ethic. The nomads’ survival was dependent on a strong sense of tribal solidarity on the basis of sharing all available resources. “The tribal ethic was founded on the principle that every member had an essential function in maintaining the stability of the tribe, which was only as strong as its weakest members. The tribal ethic was meant to maintain social egalitarianism so that regardless of one’s position, every member could share in the social and economic rights and privileges that preserved the unity of the tribe.”

During the sixth century, the Bedouins invented a saddle that enabled camels to carry far heavier loads than before. Camels then replaced donkeys for transporting the merchants’ luxury goods such as gold, precious stones, ivory, wood, spices, cotton, and silk from India; incense, ebony, ostrich feathers, gold, and ivory from East Africa; incense, myrrh, and other spices from Yemen; gum from Zufar; and pearls from the coast of Bahrain. As Mecca was conveniently located in the center of the Hijaz, it became the trade station for the caravans traveling north to Syria. Settled life was possible in this location after the rediscovery of the spring of Zamzam.

The head of the tribe, called the shaykh الشيخ, was unanimously elected by the tribe. The shaykh was the most highly respected member of the community, and usually one of the oldest. He represented the ideals of muruwah المروءة; that is, bravery, honor, hospitality, strength in battle, concern for justice, and dedication to the collective good of the tribe. All decisions related to the interest of the tribe were made by the shaykh after consultation with other prominent members of the tribe, such as the qa’id القائد war leader; the kahin الكاهن, the cultic official; and the hakam الحكم, the arbitrator. The shaykh’s main responsibility was to protect those who could not protect themselves: the poor and the weak, the young and the elderly, the orphaned and widowed.members of the tribe, such as the qa’id دئاقلا war leader; the kahin نهاكلا, the cultic official; and the hakam مكحلا, the arbitrator. The shaykh’s main responsibility was to protect those who could not protect themselves: the poor and the weak, the young and the elderly, the orphaned and widowed.

Maintaining law and peace in the tribe was the responsibility of the shaykh, who enforced the traditional law of retribution. This law was based on the concept of “an eye for an eye.” It was the responsibility of the shaykh to maintain peace and stability in his community by ensuring the proper retribution for all crimes committed within the tribe. In cases where negotiation was required, then a hakam who acted as an arbiter and would make a legal decision. Actions committed against other tribes were not considered crimes. Stealing, killing, or injuring another person was not considered morally wrong. However, if someone from one tribe harmed a member of another, the injured tribe—if strong enough—could demand retribution. In such a case, it was the responsibility of the shaykh to ensure that other tribes understood that any act of aggression against his people would be equally avenged. At the same time, it was his responsibility to negotiate a settlement if a member of his tribe committed a crime.

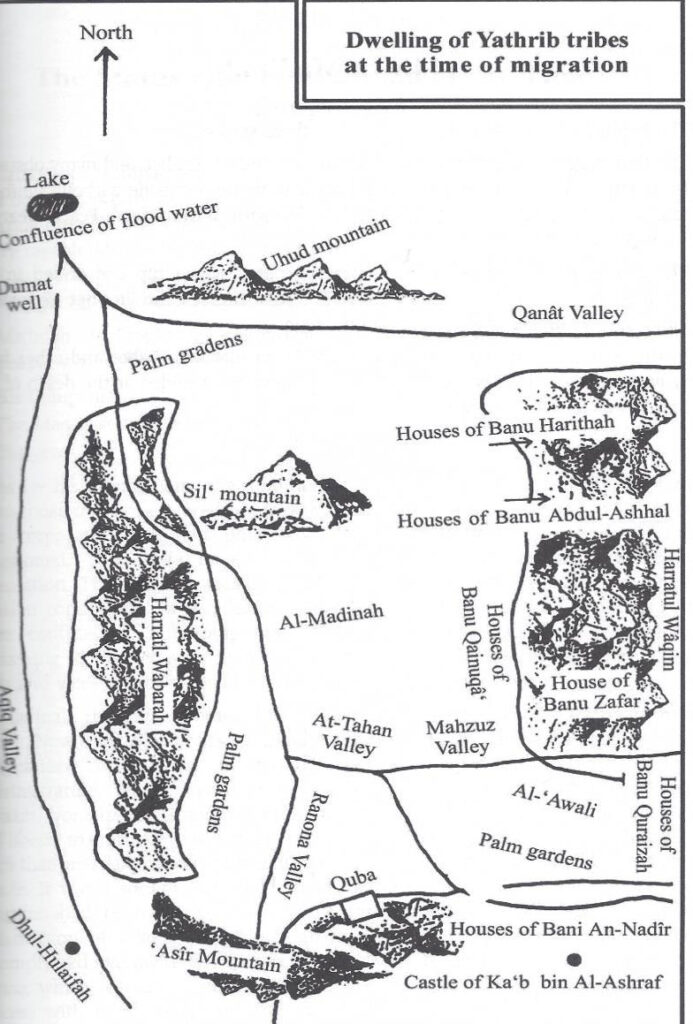

A sedentary (hadarah الحضارة) lifestyle was possible in northern Arabia in areas where enough water was available to establish and maintain agriculture. There were a few agricultural communities in the region where this was possible; Ta’if and Yathrib were among them. A sedentary lifestyle also became possible when a tribe accumulated enough wealth through other means. This happened in the north at the border with Syria, for example, when the tribe of Gassan settled on the border and became clients of the Byzantine Empire, defending Byzantium against Persia. It was also possible when a tribe accumulated enough wealth through trade, as happened in Mecca when it became a trade station.

Several factors were behind the establishment of sedentary life in mountainous, arid Mecca. The first and most important one was the discovery of an underground water source, the miraculous spring of Zamzam. Mecca’s location in the center of the Hijaz made it a trade station for the caravans traveling north to Syria, and the availability of plentiful drinking water cemented its status. It was not just water that attracted travelers to Mecca, however; the sanctity of Zamzam and the mythology behind the discovery of the spring were even more important. Nature’s gifts to the Bedouins laid down the foundation for the society’s transformation from a badawah to a sedentary one. However, the human element—that is, the vision of the leaders of the Quraysh—was behind Mecca’s transformation into the capital city of Arabia.

Mecca, the Consecrated City, Becomes the Financial Center of Arabia

During the second half of the sixth century CE, Mecca became the most prosperous city in Arabia. This transformation is attributed to the vision and wisdom of its leaders. The policies they established in governing the city and the measures they adopted in dealing with the other tribes enabled them to make Mecca the capital of Arabia. The first step in this direction was taken by Qusayy, who laid down the foundations of the institutions of government. The system of government he established was based on a balanced distribution of responsibilities and functions. He adopted a policy of involving the heads of all clans in decision making. Dar al- Nadwah was the place where the representatives of all clans met to discuss all matters that concern the community. He was always seeking their input before making important decisions. It was a government by consensus. By the standard of the time, that was quite an advanced system of government which helped Mecca to change from a semi-Bedouin town into a civilized city.

The Quraysh established the Haram مرحلأ, a zone with a twenty-mile radius with the Ka’bah at its center, where all violence and hostilities were forbidden. The Ka’bah transformed the entire surrounding area into sacred ground where fighting among tribes was prohibited and weapons were not allowed. The Quraysh made special agreements with Bedouin tribes, who promised not to attack the caravans during the season of the trade fairs; in return, these Bedouins were compensated for the loss of income by being allowed to work as guides and protectors of the merchants. The pilgrims who traveled to Mecca during the pilgrimage season enjoyed the peace and the security of the sacred grounds.

Quraysh leaders were aware of the great value of the Ka’bah as a spiritual center. They realized that combining trade and religion would advance the economy of their city. Guided by this principle, they reconstructed the architecture of the sanctuary so that it became a spiritual center for all Arab tribes. They collected the totems of the tribes and installed them in the Haram so that the tribesmen could worship their patronal deities when they visited Mecca. Unlike the other sanctuaries in Arabia, the Ka’bah was unique, as it became a universal shrine. Every god in pre-Islamic Arabia resided in the Ka’bah, which led to a deep spiritual attachment not only to the sanctuary, but also to the city of Mecca. The Quraysh created a lucrative trading zone in the city where pilgrims brought along merchandise to trade. By linking the religious and economic life of the city, Qusayy and his descendants developed an innovative religio-economic system that relied on control of the Ka’bah. During the pilgrimage season, Mecca hosted pilgrims, merchants, and commercial caravans. All caravans passing by the city would camp at the outskirts of the Meccan Valley, where their loads were assessed by Mecca’s officials; these officials collected a modest fee (tax) on all commerce that took place in the valley. The caravans would then enter the city and clean themselves at the well of Zamzam before introducing themselves to the “Lord of the House” and starting the circumambulation rituals around the Ka’bah.

Mecca during the sixth century was not just a trade station for the caravans traveling north; it was the financial center of Arabia. The Quraysh organized two commercial trips every year: to Syria in the summer and to Yemen in winter. These caravans, in which all clans participated, brought wealth to the community. They ranged in size from several hundred camel loads to almost a thousand camel loads. Meccan merchants also traveled to many parts of Africa and Asia.

Alongside the emergence of long-distance international trade, intertribal trade within Arabia began to emerge around the seasonal suqs قاوسأ (marketplaces). The suqs established regular, organized links between the sedentary communities of the peninsula. They also set the foundation for the rules of the secure zone around Mecca. The most important of these was the prohibition on fighting and raiding for four months of the year (these were the ashhur haram, “forbidden months” همرحملارهشألا ), which happened to be the months during which all of the suqs of the Hijaz and more than half of the suqs in the peninsula were held. Bedouin tribes began to exchange goods with one another. Merchants brought their goods to a series of regular markets that were held each year in different parts of Arabia; these were timed so that traders circled the peninsula in a clockwise direction. The first suq of the year was held in Bahrain, followed successively by the suqs in Oman, Hadramat, and Yemen. The cycle concluded with five consecutive suqs in and around Mecca. The last suq of the year was held in Ukaz immediately before the month of the hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca.

The Quraysh took all measures to preserve peace in the Haram zone, especially during the sacred months to prevent any disruption of commercial activities. The Quraysh were successful in achieving this goal for most of the time, except during the al-Fijar wars, which lasted for a period of four years in the late sixth century CE. A series of battles took place between the Quraysh and the Hawazin in response to a quarrel between two merchants that had occurred in the vicinity of Ukaz during one of the four holy months. The man from Hawazin was murdered by a man from Quraysh. These battles became known as the hurub al-Fijar (sinful wars بورح روجفلا). It is reported that Mecca was forced into fighting after having opted to withdraw, out of respect for the sacred month. The other tribe, the Hawazin, did not abide by the prohibition against fighting during the holy months, so the war continued for four years.

Shortly after the end of the hurub al-Fijar, a visiting Yemeni merchant from Zubayd agreed to sell some of his goods to a prominent Meccan merchant, al-A’s ibn Wa’il. Ibn Wa’il bought them all but did not pay him. When the man realized that he was about to lose everything, he appealed to several clans of the Quraysh to support him. They all declined to stand against the Meccan merchant. It became obvious that the law of retribution did not function when one party in a dispute was wealthy and powerful. In his desperation, the Yemeni from Zubayd stood on top of a hill overlooking the Ka’bah at sunrise, when the men of Quraysh gathered there. He made his appeal to them, stating his case in a passionate and desperate manner. He reminded them of their position as the custodians of the Sacred House of worship. Al-Zubayr ibn Abd al- Muttalib, an uncle of Muhammad, stood up and said that the injustice must not be allowed.

A meeting was organized in the house of Abdullah ibn Jud’an. Representatives of many clans of the Quraysh were present. The attendants gave their pledges, swearing by God that they would stand united, supporting anyone in Mecca who suffered any injustice, whether he was a Meccan or an alien. The alliance then forced ibn Wa’il to return the goods to the man of Zubayd. The alliance became known as the al-Fudul Alliance لوضفلا فلاحت, and their agreement became known as al-Fudul Covenant. This covenant aimed at preserving commercial integrity and preventing the exclusion of Yemenites or merchants of other tribes from the Meccan market.

The Quraysh managed to secure a monopoly on north-south trade so that they alone were allowed to service the foreign caravans. They also were able to control the intertribal trade, because the suqs were arranged in a way that benefited Mecca the most. The seasonal rotation around the peninsula that ended in Mecca and stayed there for four months emphasized the position of Mecca as the financial center of Arabia. Its location in the center of the Hijaz, surrounded by vast desert, gave Mecca relative isolation from Byzantium and Persia, the great powers of the region. Neither of them had any interest in the difficult terrain of Arabia, so the Quraysh could create a modern economy without imperial control. The separation from the great powers led to an independent economy that was immune to the decline of these empires’ fortunes. In the late part of the sixth century and the start of the seventh, Persia and Byzantium were engaged in debilitating wars with one another which resulted in both being weakened. Because these wars were fought across Syria and Mesopotamia the trade routes in these regions were abandoned. The Quraysh took advantage of the situation by gaining control of the intermediary trade between north and south. This period also witnessed the decline of Yemen and serious conflicts among several trading peninsular tribes. All these factors enhanced Mecca’s position and contributed to the success of the Quraysh in their efforts to monopolize trade in Arabia.

Mecca’s competitors realized that its innovative religio-economic system was behind its growth and increased wealth. This is why the Abyssinians tried to destroy the Ka’bah after constructing their own pilgrimage center in Sana’h. They targeted Mecca’s sanctuary, not because the Ka’bah was a religious threat, but because Mecca was an economic rival.

Mecca enjoyed its position as the largest city in Arabia. The Quraysh leaders became extremely wealthy. The prominent merchants controlled most of the wealth. The wealthy people were controlled by the rules of the market economy—ruthless competition, greed, and individual enterprise—not the communal spirit and tribal ethics. The wealthy clans were engaged in fierce competition with one another for wealth and prestige. Instead of sharing their wealth with the other members of the community, they were hoarding it and building private fortunes. They not only ignored the plight of the poor, but exploited the rights of orphans and widows. The principles of muruwah seemed incompatible with the market economy. Cruelty, unjust practices, and depriving others of their rights by force went unpunished. This inevitably led to tension and the destruction of the fabric of Meccan society.

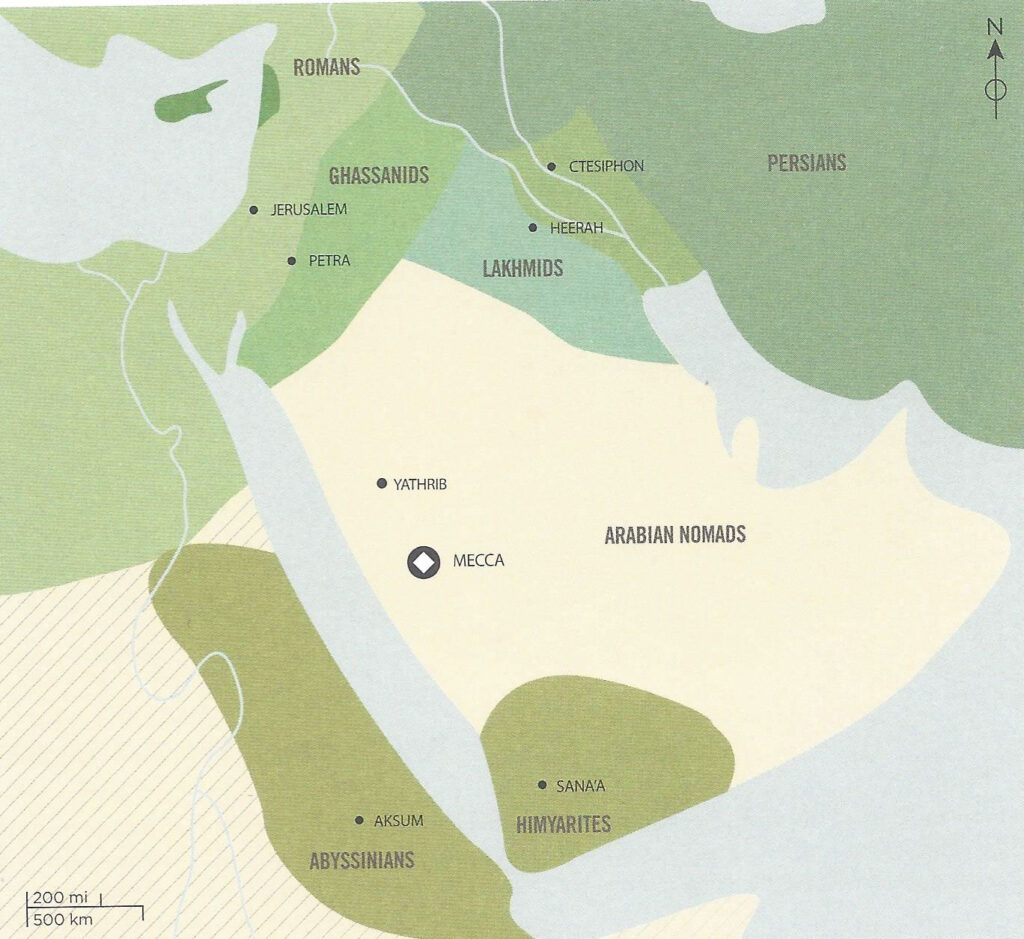

The Great Powers Surrounding Arabia

The Near East in the sixth century CE was divided between two great empires: the Roman Empire in the west and the Persian Empire in the east. The Roman Empire was known as the Eastern Roman Empire or the Byzantine Empire. The western part of the Roman Empire had ceased to exist in the fifth century after it was overrun by barbarians. The Byzantine Empire, with its capital, Constantinople, survived and was able to expand in the sixth century. It included Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt, North Africa, and southeastern Europe. It also controlled the Mediterranean Islands and part of Italy. The Persian (Sassanian) Empire was known as Iran or Iranshahr. The Sassanids came to power in 224 CE, and retained their dominance until the mid- seventh century. Their territory included modern-day Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, eastern Syria and Turkey, part of the Caucasus, and the Persian Gulf.

The two empires were engaged in many wars between the fourth and sixth centuries in an effort to protect or extend their territories. Both empires were interested in controlling the key zones of Mesopotamia and Armenia and establishing alliances with lesser states in the region. The Christian kingdom of Aksum was a Byzantine client-state. Byzantium also controlled Arab tribes on the border of Palestine and Syria. The Sassanians established several protectorates over Arab tribes on the East Arabian coast and in Oman.

Both empires were interested in financial and economic gain from profitable trade with the Orient. Different products were brought from the East to the Mediterranean basin: southern Arabian incense, Chinese silk, Indian pepper and cotton, spices, and other products from the Indian Ocean region. Arabia occupied a strategic position in trade with the Orient, which led both Byzantium and Persia to intervene in its affairs. In 525 CE Byzantium encouraged Aksum to invade the kingdom of Himyar in Yemen in order to control the Red Sea trade route to the Indian Ocean. In 575 CE, the Sassanians marched into southern Arabia and ousted the Aksumites from Yemen and appointed a governor from the Himyarites to rule Yemen as a client-state.

At the beginning of the seventh century CE, Persia started a massive military campaign against Byzantium, and between 611 and 620 CE was able to achieve major victories against Byzantium, seizing most of Anatolia, all of Syria-Palestine, and Egypt. In 614 CE, Persian forces entered Jerusalem and took away the True Cross. But in 622 CE, the Byzantine Heraclius emperor began his military campaign against the Persians. His campaign was successful, ending in decisive victory in 628 CE with Byzantium regaining all its territories, including Jerusalem. They were also able to expand the Byzantine Empire to include most of Mesopotamia. Two years later, Byzantium recovered the Holy Cross.

In the third and fourth centuries, the Byzantine emperors declared themselves champions of Christianity. In the sixth century the majority of the Near Eastern population were Christians, but they were divided into several sects. The official church of the Byzantine Empire was the Greek Orthodox. Christians following the teachings of Bishop Nestorius (Nestorianism) were forced to leave the Byzantine Empire after Nestorius was deposed for heresy by the Council of Ephesus in 431 CE; they took refuge in the Sassanian Empire. Another Christian sect, the Monophysites, was declared heretical by the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE. Monophysitism was the creed of most Christians in Aksum, Egypt, Syria-Palestine, Mesopotamia, Armenia, and Iran.

The Sassanian kings embraced Zoroastrianism as their official religion. The majority of the population of Iran and southern Mesopotamia were Zoroastrians. Although both the Byzantine and the Sassanian empires embraced the official religions of their countries, large populations of Jews were scattered throughout the Near East in major cities such as Alexandria, Jerusalem, Tiberias, Antioch, Hamadan, Rayy, Susa, Constantinople, and Ctesiphon. Communities of all the three revealed scriptural religions—Christianity, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism—were also found in Arabia.

The Abyssinians

The Abyssinians were the third major empire bordering Arabia. Established around 400 BC, they embraced Christianity in the third century CE. They controlled the Horn of Africa, the Red Sea coast, and occasionally Western Arabia. They also controlled Yemen between 521 and 570 CE.

The Himyarites

It is believed that around 2500 BCE, Yemen was settled by the Qahtanian Arabs, who founded the empire of Saba (Sheba). Between 1300 and 650 BCE, they built the Dam of Ma’rib, which helped them to irrigate two adjacent valleys. This irrigation system allowed the empire to grow into a prosperous civilization that controlled the surrounding areas.

Around the second century CE, the Qahtanians were divided into two branches: Himyar and Kahlan. The Himyar branch stayed in Yemen, while the Kahlan branch was forced out. They spread north throughout the Arabian Peninsula. The following tribes belong to the Kahlan: Khuza’ah, Aws, Khazraj, Ghassan, and Lakhm.

After expelling the Kahlan, the Himyarites controlled Yemen between 115 BCE and 450 CE. However, the fractured empire was never able to regain its control over Arabia. It was intermittently invaded by Abyssinians, Persians, and Romans. Around 450 CE, cracks appeared in the ancient Ma’rib Dam, leading to great flooding in the region.

Besides the Qahtanians, a second group of tribes called the Adnanians originated in the central Arabian Peninsula (Hijaz and Najd). Among these were the Hawazin, Ghtafan, Thaqif, and Quraysh.

The Ghassanids

The Ghassanids were among the Kahlans who were expelled from Yemen by the Himyarites. They settled in northern Arabia and established their own kingdom, which included parts of modern-day Syria, Jordan, and Palestine. Their capital was Jaliyah, located in what is now the Golan Heights. They allied themselves with the Romans and defended the Roman territories against the Lakhmids and Persians. They were Monophysite Christians.

The Lakhmids

The Lakhmids were also among the Kahlans who were expelled from Yemen. They settled in northeastern Arabia. They were supported by the Persians against the Ghassanids and the Romans and provided the same service of protecting their borders. They became Nestorian Christians.

Religious Beliefs in Arabia before Islam

The Arabian Peninsula was dominated by paganism before Islam. While the term “paganism” does not have a definite meaning, it was introduced by the Monotheists to describe those who do not believe in the oneness of God. In sedentary pre-Islamic Arabia, many people believed in a single high god without rejecting the existence of other, subordinate gods. The German scholar Max Miller termed this concept Henotheism. The earliest evidence of Henotheism in Arabia can be traced back to a tribe called the Amir who lived near modern-day Yemen in the second century BCE, and who worshipped a high god called dahu-Samawi, ‘The Lord of the Heavens.’ By the sixth century CE, Henotheism had become the standard belief of the vast majority of sedentary Arabs, who accepted Allah as their high god.

Allah was originally an ancient rain/sky deity who had been elevated into the role of the supreme god of the pre-Islamic Arabs. Allah, as the high god in the Arab pantheon, was difficult for ordinary people to reach. His intercessors were easier to reach. The most powerful among his intercessors were his three daughters, al-Lat (the goddess), al-Uzza (the mighty), and Manat (the goddess of fate). Arabs believed that God had married the djinn and produced angels as his daughters through that marriage. These divine mediators were not only represented in the Ka’bah, but they had their own individual shrines: Al-lat in Ta’if; al-Uzza in Nakhlah; and Manat in Qudayd.

The Ka’bah was a small, roofless structure that housed the 360 gods of pre-Islamic Arabia, representing every god recognized in the Arabian Peninsula. Among the most famous were Hubal, the Syrian god of the moon; al-Uzza, the powerful goddess the Egyptians knew as Isis and the Greeks as Aphrodite; al-Kutba, the Nabataean god of writing and divination; Jesus, the incarnate god of the Christians; and Jesus’s holy mother, Mary.

The original Ka’bah was nine arms in height. At the beginning of the seventh century CE, the Quraysh decided to rebuild it; the height was then increased to eighteen arms. When Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr rebuilt the Ka’bah some ninety years later, he expanded it to its present height of twenty-seven arms.

During the holy months, pilgrims from all over the peninsula would make their way to Mecca to visit their tribal deities. As they reached the Ka’bah, they sang songs of worship and danced in front of the 360 gods; then the pilgrimage rituals began. Two of the rituals were performed around the Ka’bah: Jogging seven times between the hills of Safa and Marwah, هورملاو افصلا to the east of Ka’bah; and gathering as a group and jogging around the Ka’bah seven times. The origin of the first ritual is the myth of Hagar jogging between the two hills looking for help, when water gushed forth between her son’s feet. The origin of the second ritual, tawaf فاوط (circumambulation), is a mystery. Pagan Arabs believed that this ritual was initiated by Abraham after he completed the construction of the Ka’bah. As the pilgrims jogged around the Ka’bah, they were following the course of the sun around the earth, and this way they were putting themselves in harmony with the fundamental order of the cosmos. A black stone (دوسألأ رجحلا)—a piece of meteoric basalt—embedded in the eastern wall of the Ka’bah helped them to orient and count the seven times of circumambulation. The pagan Arabs believed that this stone had fallen from the sky, linking heaven and earth.

Other duties of pilgrimage were done outside the boundaries of the Haram area in about a twenty-kilometer radius around Mecca. These rituals included visiting Mount Arafat, افرع. It was commonly held that no pilgrimage was valid unless the pilgrim was present at Arafat on the ninth day of Dhul-Hijjah, the last month of the lunar year. This visit to Arafat was followed by an all-night vigil on the plain beside the mount, an area called Muzdalifah, هفلدزملا, the home of the thunder god. The final ritual was hurling pebbles at three pillars in the valley of Mina ىنم, symbolizing stoning Satan. Finally, the pilgrims sacrificed their most valuable female camels.

The monotheistic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism were present in pre- Islam Arabia, and influenced the religious beliefs of the Arabs. The pagan Arabs were familiar with Judaism and the Old Testament. They considered themselves descendants of Abraham. They believed that Abraham had rebuilt the Ka’bah and created the pilgrimage rites that took place there. In the sixth century CE, Arabs associated their god, Allah, with the Jewish god Yahweh. Jews in Arabia, whether in Yemen or in the north, were converts. There were Jewish merchants, Jewish Bedouins, Jewish farmers, Jewish poets, and Jewish warriors through Arabia. Jewish men took Arab names; Jewish women wore Arab headdresses. The primary language of the Jews of Arabia was the Arabic, not Aramaic. Judaism in Arabia was different from traditional Judaism. The Arab Jews shared many of the same religious ideals of pagan Arabs.

Christianity surrounded Arabia to the northwest (Syria), the northeast (Mesopotamia), and the south (Abyssinia). Many Arab tribes had converted to Christianity, the largest among them being the Ghassanids in the north. The Byzantine emperors sent missionaries to spread Christianity among pagan Arabs. Christianity’s presence in the Arab Peninsula influenced the pagan Arabs in many ways. Arabs were familiar with the New Testament. A picture of Jesus the incarnate god was placed in Ka’bah, as well as a picture of his mother, Mary.

Zoroastrianism was the dominant religion of the Persian Empire. In the tenth and eleventh centuries BCE, its prophet Zarathustra preached a unique monotheistic religion based on the sole od Ahura Mazda, “the Wise Lord.” Although Zoroastrianism was a non-proselytizing religion, the Sassanian military presence in the Arabian Peninsula resulted in a few tribal conversions to Zoroastrianism.

The presence of these three monotheistic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism—had an effect among the people of Arabia, and created a breeding ground for new ideologies. A unique Arab monotheistic movement, Hanifism فنحلا, appeared in the Hijaz around the sixth century CE; this also had an important effect on future Arab religious beliefs.

Muslim historians mention the most prominent hanifs. In his biography of the Prophet Muhammad, ibn Hisham names four men: Waraqa ibn Nawfal, Uthman ibn Huwairith, Ubayd Allah ibn Jahsh, and Zayd ibn Amr. These four men made a solemn pact to follow the religion of Abraham, whom they considered to be neither a Jew nor a Christian, but a pure monotheist, a hanif, which means in Arabic “to turn away from idolatry.” The four hanifs bonded together in strong friendship and started to preach the new religion. In the end, two of them— Waraqa and Uthman—converted to Christianity. Ubayd Allah converted to Islam and was one of the Muslims who emigrated to Abyssinia. While in Abyssinia he embraced Christianity and died a Christian. Zayd continued preaching Hanifism and criticizing idolatrous worship. He tried to save every young girl who was to be buried alive by her father. Such activities angered his uncle al-Khattab, who managed to banish him to an area outside Mecca. However, Zayd managed to escape and left Arabia. He traveled widely in Syria and Iraq. While traveling, an aged Christian priest told him that the time was ripe for the appearance of a new Prophet in Arabia. Therefore he immediately decided to return to Mecca. Unfortunately, he was murdered on his way home.

The Hanifism movement flourished throughout the Hijaz, especially in major population centers such as Ta’if and Yathrib. Among the hanif leaders in the Hijaz were Abu Amir ar- Rahib, Abu Qais ibn al-Aslat, Khalid ibn Sinan, and Qass ibn Sa’idah. Hanifism was a mature Arab monotheistic movement. The hanifs believed in one god, the Creator, who did not need mediators between him and humans. They were committed to an absolute morality. Zayd, who was a poet, said:

“I serve my Lord the compassionate,” “The forgiving Lord may pardon my sin.” “Beware, O men, of what follows death!” “You can hide nothing from God.”

Many scholars believe that the Prophet Muhammad was influenced by Hanifism. Ibn Hisham mentions that the Prophet had met Zayd.

On one of the hot days of Mecca, Muhammad and his childhood friend Ibn Haditha met Zayd at the upper part of the Meccan Valley when they were returning home from Ta’if. In Ta’if, they had slaughtered and roasted a lamb in sacrifice of the idols [most likely al-Lat].

Muhammad asked Zayd: “Why do I see you, O son of Amr, hated by your people?”

“I found them associating divinities with God and I was reluctant to do the same,” Zayd replied.” I wanted the religion of Abraham.”

Muhammad accepted this explanation without comment and opened his bag of sacrificed meat. “Eat some of this food, O my uncle,” he said. But Zayd reacted with disgust. “Nephew, that is a part of those sacrifices of yours which you offer to your idols, is it not?” Muhammad answered that it was. Zayd became indignant. “I never eat of these sacrifices, and I want nothing to do with them,” he cried. “I am not one to eat anything slaughtered for a divinity other than God.”

So struck was Muhammad by Zayd’s rebuke that many years later, when recounting the story, he claimed never again to have “stroked an idol of theirs, nor. .. sacrificed to them until God honored me with his Apostleship.”

This narrative indicates that a young pagan Muhammad could have been scolded by a hanif. It is a common belief in Islam that even before being called by God, Muhammad never took part in the pagan rituals of his community. But the ancient traditions clearly show Muhammad deeply involved in the religious customs of Mecca: circumambulating the Ka’bah, making sacrifices, and going on pagan devotional retreats called tahannuth. Indeed, when the pagan sanctuary was torn down and rebuilt (it was enlarged and finally roofed), Muhammad took an active part in its reconstruction. In addition, the Quran does state that God found Muhammad “erring” and gave him guidance:

And your Lord will give you, and you will be satisfied. Did He not find you orphaned and sheltered you?

(Chapter 30, adh-Duha)

And found you wondering, and guided you? And found you in need, and enriched you?

Muhammad Pre-Revelation

Muhammad was born into the clan of Hashim, one of the most prominent clans of the Quraysh, in the latter half of the sixth century CE. Muslim historians picked the year 570 CE as Muhammad’s birth year in order to institute a firm Islamic chronology. The clan of Hashim were the custodians of the Ka’bah, and had the privilege of providing the pilgrims with water. Muhammad’s grandfather, Abd al-Muttalib, was one of the most visionary rulers of Mecca and the most respected leader of the Quraysh. He had been the first merchant to organize his own independent trade caravans between Yemen and Syria.

Abdullah, Muhammad’s father, was the youngest of Abd al-Muttalib’s ten sons, and the most favored by his father. In his early twenties, Abdullah married Aminah, the daughter of Wahb ibn Abd Manaf, who was the chief of the Zuhra clan. It was a happy marriage, and both partners soon became very fond of each other. Shortly after Abdullah got married, his father advised him to join a trade caravan bound for Syria. His goal was to prepare his youngest son to become a successful merchant. As Abdullah was about to start on his journey, Aminah gave him the happy news that she was pregnant.

Traveling in the desert in the blazing summer was very hard on Abdullah. On his return to Mecca, he became very sick. His condition was very serious, and he was forced to stay behind in Yathrib to recover and regain his strength. Unfortunately, he died away from home. His death at that young age was devastating for Abd al-Muttalib in his old age, as well as for Aminah, the young bride who was expecting a baby who would now be fatherless.

While Aminah was pregnant, she heard a voice tell her, “You are pregnant with the Lord of this people, and when he is born, say: “I put him in the care of the One from the evil of every envier, then call him Muhammad.” Sometimes Aminah would see a light shining from her belly by which she could make out “the castles of Syria” (a reference, perhaps, to Muhammad’s prophetic succession to Jesus, as Syria was an important seat of Christianity). This story is remarkably similar to the Christian story of Mary, who, when pregnant with Jesus, heard the voice of the Lord declare, “You will be with child and will give birth to a son, and you are to give him the name Jesus. He will be great and will be called the son of the Most High.” (Luke 1:31–32).

When Aminah delivered her baby, her father-in-law, Abd al-Muttalib, who was greatly saddened by the loss of his son, was delighted, and overcame his grief with his hopes for a bright future for the newborn child. He thanked God for giving him a boy to bear the name of his deceased son. Aminah named her baby Muhammad, which means “often praised” or “worthy of praise.” It was a totally unfamiliar name in Arabia.

The tradition among the elites of Mecca was to send their children to the desert to be nursed by a Bedouin wet nurse. They believed that when a child was nursed in the desert, he was certain to grow up strong and healthy. As an infant, Muhammad was placed in the care of a Bedouin foster mother, Halimah, to be nursed. He stayed with Halimah for four years, and then he was returned to his mother.

When Muhammad was six years old, he traveled to Yathrib with Aminah to visit the clan of al-Najjar, his maternal uncles. (Abd al-Muttalib’s mother belonged to the al-Najjar clan). After they stayed for a month in Yathrib, Amina decided to return to Mecca. Shortly after they started their journey, Aminah fell ill. It was a quick and fatal illness. She died on the road and was buried at Abwala.

After Aminah’s death, Muhammad was placed in the care of his grandfather, Abd al- Muttalib. Muhammad received special treatment from his grandfather, who kept him close by all the time; he had him sit on his couch beside him when he met with other Meccan notables. Abd al-Muttalib was concerned about Muhammad’s future care upon his death, so he called his son Abu Talib and asked him specifically to look after Muhammad, his nephew, when he himself had died. Abd al-Muttalib chose Abu Talib for this task because Abu Talib and Abdullah, Muhammad’s father, had the same mother (from the al-Najjar clan).

Upon the death of Abd al-Muttalib at age eighty-two, Abu Talib assumed the responsibility of taking care of Muhammad, who was eight years old at the time. Muhammad was extremely distressed over the loss of his grandfather; he felt that he had lost the man whose kindness to him could not be equaled by any other. Abu Talib honored his father’s request, taking care of Muhammad throughout his entire life, from when he was young to when he became a man. Abu Talib gave Muhammad, the Prophet, his steadfast support in the face of strong opposition from the Quraysh until the day he died.

When Abd al-Muttalib died, Muhammad inherited nothing, as his more powerful relatives controlled the estate. He went to live with his uncle Abu Talib, who became the chief of the Hashim. Abu Talib was greatly respected in Mecca, even though his business was failing. It was Abu Talib who protected Muhammad from falling into the debt and slavery, which was the typical fate of orphans in Mecca. Abu Talib provided Muhammad a home and the opportunity to work for his caravan. He was very fond of his nephew. Hamzah, the youngest of Abd al-Muttalib’s sons, instructed Muhammad in martial arts, making him a skilled archer and competent swordsman. His uncle Abbas, a banker, was able to get Muhammad a job managing the caravans traveling north to Syria.

The young Muhammad was well-liked in Mecca. He was handsome, with a compact, solid body of average height. His hair and beard were thick and curly, and he had a strikingly luminous expression and a smile of enormous charm. He was decisive and wholehearted in everything he did. When he turned to speak to somebody, he would swing his entire body around and address him full face. When he shook hands, he was never the first to withdraw his own. He inspired such confidence that he was known as al-Amin, “the trustworthy.” But his orphaned status constantly held him back. He asked his uncle, Abu Talib, to marry his cousin Fakhitah, but Abu Talib had to refuse his request for her hand, gently pointing out that Muhammad could not afford to support a wife.

Muhammad was talented and proved himself as a skillful merchant who knew how to strike a deal. He was well known in the community for his honesty and morality, which earned him high respect in Meccan society. He had no money of his own to establish a business, nor was his uncle Abu Talib able to provide him with a good start. The only option left for him was to prove himself as an agent, trading on someone else’s behalf. Apparently, he had no difficulty securing such a position because of his known reputation for honesty and good character. He was successful in his trade efforts at different markets and bazaars. The turning point in his life was working as an agent for a rich widow, Khadijah bint Khuwaylid. His outstanding performance as a trader prompted her to hire him to lead one of her caravans to Syria. His first trip was a great success; he was able to make twice as much profit as she had hoped.

Khadijah, being a wealthy widow, received several marriage proposals. She realized, however, that her money was what had prompted these proposals, so she declined them all. She was a woman of great intelligence and strong character. Her business relationship with Muhammad made her recognize that money was not the greatest priority for him. She considered the idea of marrying Muhammad after consulting her uncle Waraqa ibn Nawfal, who recognized that Muhammad was destined to have great future.

Khadijah then sent a close friend of hers, Nufaysah bint Munyah, to make an indirect approach to Muhammad. When she met him, she said: “Muhammad, what is keeping you from getting married?” He answered, “I do not have enough to meet the expense of my marriage.” She said, “What if you are not called to meet that expense? What would you say to a woman of beauty, wealth, and position who is willing to marry you; would you marry her?” He said, “Who is that woman?” She said, “Khadijah.” He asked, “Who can arrange such a marriage for me?” She said, “Leave that to me.” His response was, “I will do it willingly.”

This conversation was followed by direct communication between Khadijah and Muhammad, which ended in a formal marriage ceremony.

It was a happy marriage. Most biographers of the Prophet put his age at twenty-five and Khadijah’s at forty. Some reports suggest that the Prophet was around thirty, and Khadijah was reported to have been thirty-five or younger. In view of the fact that she gave Muhammad six children, the report of Khadijah being younger than forty is most likely accurate. Abdullah ibn Abbas, the Prophet’s cousin, states that she was not a day older than twenty-eight.

Muhammad spent twenty-five happy years with Khadijah. The marriage gave Khadijah a man whom she could love, respect and trust. He was a most caring and loving husband. Khadijah bore Muhammad four daughters and two sons. The first was a boy, who was named al-Qasem. Then came four daughters: Zaynab, Ruqayyah, Umm Kulthum, and Fatimah. Abdullah was the last child. Al-Qasim lived only few years, while Abdullah died in infancy. The first three daughters died while Muhammad was living in Madina, while Fatimah survived him, but died six months after his death. Although polygamy was common in Arabia, Muhammad did not have a second wife while Khadijah was alive.

Khadijah was keen on marrying her daughters to suitable men. She arranged for the marriage of her eldest daughter, Zaynab, to her favorite nephew, Abu l-’As ibn Ar-rabi’, when she reached the traditional marriage age. Muhammad’s maternal half-uncle, Abu Lahab, requested that Ruqayyah and Umm Kulthum be engaged to his sons Utbah and Utaybah. Muhammad and Khadijah agreed. It appeared that Abu Lahab had high expectations that his nephew would be a leader of the next generation.

Prior to his marriage, Muhammad inherited a servant named Baraka from his father. She took care of Muhammed when he was with his mother, and continued to take care of him when he was with his grandfather and uncle. On the day he married Khadijah, he freed Baraka. Khadijah also had a servant at that time, a fifteen-year-old boy named Zayd ibn Harith, whom she gave to Muhammad as a wedding gift. Zayd was from the northern tribe of Kalb, between Syria and Iraq, where he had been abducted and sold as a slave. Shortly after the marriage, Zayd met pilgrims visiting from Banu Kalb. They sent word to his family that he was safe in Mecca. Upon hearing the news, his father, Harith ibn Sharahil, came to Mecca to pay for Zayd’s freedom. Muhammad freed Zayd for no money, but when he told Zayd he was free to return to his family, Zayd replied, “I would not choose any man in preference to thee. Thou art unto me as my father and mother. .. I have seen from this man such things that I could never choose another above him.”

After hearing those words, Muhammad invited Zayd’s father and uncle to join him at the Ka’bah, where he publicly proclaimed, “All ye who are present, bear witness that Zayd is my son; I am his heir and he is mine.”

By the turn of the seventh century, Abu Talib was struggling to support his large family. Muhammad approached his uncle Abbas, and suggested that they each take care of one of Abu Talib’s children. Ja’far, fifteen, went to live with Abbas. Ali, who was no older than five, went to live with Muhammad.

Muhammad’s marriage to Khadijah elevated his status in Meccan society. He was extremely successful in managing his wife’s business and enhancing her wealth. He became well known as an affluent merchant, respected for his fair and ethical conduct. Despite his great success in business and improved social status, he did not become part of the ruling elite of Mecca. He definitely had the greatest opportunity to accumulate more wealth and reach the top position among the ruling elites. His uncle Abu Lahab saw that when he asked for Ruqayyah and Umm Kulthum to be engaged to his sons: he believed that his nephew would be the leader of next generation. But Muhammad was distressed over the serious changes in Meccan society wrought by the market economy and Mecca’s religio-economic system. He realized that the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few ruling families not only altered the social and economic landscape of Mecca, but also destroyed the tribal ideals of social egalitarianism. He was troubled by the absence of any concern for the poor and the marginalized and for the disappearance of the tribal ethic which held that “the tribe is only as strong as its weakest members.” He saw the Meccan society as stratified: leaders of the ruling families of the Quraysh were at the top, while those with no protection, like orphans and widows, were at the bottom. He was not interested in accumulating more wealth, but in finding solutions.

Muhammad was able to diagnose the serious ills of Meccan society. He was aware of the restlessness among the younger generation. The ruling elites had introduced class distinctions that were alien to the muruwah ethical ideals. The wealthier families lived beside the Ka’bah, while the less prosperous inhabited the suburbs and the mountainous regions outside the city. He was convinced that the Quraysh had retained only the worst aspects of muruwah: recklessness, arrogance, and egotism that were morally destructive and could bring the city down. He was convinced that social reforms were overdue.

Muhammad was not only concerned about the social and economic situation in Mecca, but about the religious aspect as well. The encounter Muhammad had had with the hanif Zayd ibn Amr when he was very young affected his religious beliefs. His trips to Syria put him in contact with Christian Arabs. Over the years, he was able to learn more about the concept of monotheism through the exposure to Judaism and Christianity.

Muhammad’s concern for Mecca’s troubles and problems made him seek solitude. On one of the rocky hills outside Mecca, he found a cave named Hira ءارح راغ. He began spending several nights at a time in this cave, praying and meditating. During these solitary vigils he began to have strange experiences which ultimately led to his divine revelation.

The Revelation of Muhammad

One night in 610 CE, while Muhammad was meditating alone in the cave of Hira ءارح راغ, he experienced the most astonishing attack. Suddenly an invisible presence embraced him, crushing his chest. He struggled to free himself but could not move. The pressure in his chest increased until he could no longer breathe. As he surrendered his final breath, light filled the cave and a terrifying voice came loud and clear: “Recite!” Muhammad responded, “What shall I recite?” The invisible presence tightened its embrace and said, “Recite!” Muhammad asked again, “What shall I recite?” Once more the presence tightened its grip and once more repeated the command: “Recite!” Finely as the pressure in his chest stopped, he felt these words enter his heart:

Read: In the name of your Lord who created. Created man from a clot.

(Chapter 30, al-’Alaq)

Read: And your Lord is the Most Generous. He who taught by the pen.

Taught man what he never knew.

This was a terrifying experience for Muhammad. He managed to make his way back home, frightened and trembling. As he arrived home, he asked Khadijah to wrap him up. She threw a cloak over him and held him tightly in her arms until the trembling stopped. When he calmed down he explained to her what happened to him, then said, “Khadijah, I think that I have gone mad.” Khadijah replied: “This cannot be, my dear. God would not treat you thus, since He knows your truthfulness, your great trustworthiness, your fine character, and your kindness.” Khadijah went to her cousin, Waraqa, who as a Christian was familiar with the scriptures. He recognized what Muhammad was experiencing. He assured her, saying, “He is a Prophet of this people; bid him be of good heart.”

In writing the Prophet’s biography, Muslim historians present varying descriptions of the experience in the cave of Hira. Ibn Hisham states that Muhammad was sleeping when the revelation first came to him, and says that the command iqra (أرقإ) was intended to mean “read.” In fact, according to ibn Hisham, the first recitation was actually written on a magical brocade and placed in front of Muhammad. Al-Tabari claims that the Prophet was standing when the revelation dropped him to his knees; he also believes that the command iqra is best understood as “recite.”

Muslim tradition has tended to focus on al-Tabari’s definition of iqra (“recite”), as it emphasized the notion that the Prophet was illiterate, which some say is validated by the Quran’s epithet for Muhammad: an-nabi al-ummi يمألا يبنلا, traditionally interpreted as “the unlettered Prophet.” But while Muhammad’s illiteracy may enhance the miracle of the Quran, there is no historical justification for it. As numerous scholars and Arab linguists have demonstrated, an- nabi al-ummi should be understood as “the Prophet for the unlettered” (that is, the scriptureless), consistent with Muhammad’s view that the Quran was a revelation for a people without a sacred book:

But We gave them no books to study, and We did not send them any warner before you.

(Chapter 22, Saba’)

It is highly unlikely that a successful merchant like Muhammad would have been unable to read and write while running his own business. Obviously, he was not a scribe, or a scholar, or a poet. But he must have been able to read and write basic Arabic, such as names, dates, goods, and services.

The terrifying experience that Muhammad had at Hira kept him in a state of confusion. An urgent issue occupied his mind and consciousness: What does this experience mean and what is next? He was assured by Waraqa ibn Nawfal that God was sending him a message and that he was now God’s Messenger. Over the following days he was waiting for answers and expecting another revelation. During this period of silence, he became very anxious and started doubting himself. Finally, when he was at his lowest, a second verse was sent down from heaven in the same violent manner. The new message was assuring and affirming that he was the messenger of God:

O, You enrobed one. Arise and warn;

(Chapter 29, al-Muddathir)

And magnify your Lord. And purify your clothes. And abandon abominations.

And show no favor seeking gain. And be constant for your Lord.

Responding to God’s command, Muhammad began his mission.

The Initial Call to Islam (The Secret Call)

The initial call to Islam was a secret call targeting selected members of the community. This period lasted for approximately three years. Prophet Muhammad initiated his sacred, secret mission right from home and then moved to the people closely associated with him. Khadijah was the first to accept the new religion. His cousin Ali ibn Abi Talib, who had been living with him since his early childhood; Zayd ibn Harith, his adopted son; and his close friend Attiq ibn Uthman نامثع نبا قيتع—who is known by his title, Abu Bakr As-Saddiq قيدصلا ركب وبا—accepted Islam next.

Abu Bakr was a well-respected merchant whose house was frequently visited by many people seeking his friendship and knowledge. He invited whomever he trusted to join the faith of Islam. A good number of his friends and acquaintances converted to Islam. Abu Bakr introduced to Muhammad a group of five men who became the main prominent leaders of the young Islamic state during Muhammad’s life and the years after. Those five men were Uthman ibn Affan al-Umawi يومألا نافعع نبا نامثع, Az-zubair ibn Awam Al-asadi يدسألا نوع نبا ريبزلا, Abdur-Rahman ibn Awf فوع نبا نامحرلا دبع, Sa’d ibn Abi Waqqas az-Zuhriyan صاقّو يبأ نبا دعس نايرهزلا, and Talhah ibn Ubaidullah At-Atimy يميتلا هللا ديبع نبإ هحلط.

Among the early Muslims were Bilal ibn Rabah يشبحلا حابر نبإ لالب, Abu Ubaidah Amir ibn Al-Jarah from Banu Harith ibn Fihr رهف نبإ ثراح ينب نم حارجلا نبإ ريمأ هديبع وبأ, Abu Salamah ibn Abdul-Asad دسألا دبع نبإ هملس وبأ, al-Arqam ibn Abul-Arqam from the tribe of Makhzum نبإ مرقألا موزخم ةليبق نم مرقألا وبأ, Uthman ibn Maz’on and his two brothers Qudamah and Abdullah نبإ نامثع هللا دبع و همادق هيوخأ و نوذأم, Ubaidah ibn Harith ibn al-Muttalib ibn Abd Manaf نبإ ثراح نبإ هديبع فانم دبع نبإ بلطملا. Among the early followers were Said ibn Zaid Al-Adawi and his wife Fatima (daughter of Omar ibn al-Khattab) باطخلا تنبإ همطاف هتجوز و يودعلا ديز نبإ ديعس, Khabbas ibn al-Aratt تارعلا نبإ سابخ, Abdullah ibn Mas’ud al-Hadhali يلهدهلا دوعسم نبإ هللا دبع, and many others. These were known as the first of Muslim forefathers. They belonged to various clans of the Quraysh. Ibn Hisham, a biographer of the Prophet, estimated their number to be more than forty.

The first Muslims who accepted Islam during the first three years fall into three groups. The first group included young men under thirty whose families and clans were among the most influential. They were close relatives of the men who actually held power in Mecca and who became the strongest opponents to Muhammad. The second group consisted of young men, again under thirty, from less prominent families and clans. This group was not sharply distinguished from the first group, but strongly influenced their clans and families. Some members of this group were Arabs from outside Mecca attached to clans as “confederates.” The men of the first two groups were from the upper levels of society, but they felt the same discontent with Meccan society as Muhammad did. The third group comprised a number of men who were outside the clan system; these included foreigners of Byzantine or Abyssinian origin who might originally have come to Mecca as slaves. Usually such men were nominally under clan protection, but the clan was either unwilling or unable to protect them. Hence the early Muslims came from different clans, and different social classes. Interestingly, many of them were women.

The early Muslims enjoyed equality and a brotherhood which was above blood relationships. They formed the nucleus of a community of believers which would create the most noble society humanity had ever known in its long history. Their headquarters was the house of al-Arqam, located near the center of Mecca. Al-Arqam was a young man about twenty-five years old who belonged to the clan of Makhzum, which was among the wealthiest and most powerful in Mecca. The house of al-Arqam was the first Islamic school. Here, the followers of the new religion received their instructions directly from the Prophet. Muhammad spent a considerable amount of time in that house looking after his companions, educating them and guiding them in their new mission.

The Earliest Message of the Quran

The main theme of the early verses of the Quran was the goodness and power of God. He is the creator of humans. He is behind all forces of nature, and all that exists around humans. He is the provider of all that humans need for sustenance and survival. He is ar-Rahman, نامحرلا “the most merciful,” and al-Akram, مركألا “the most generous.”

Perish man! How thankless he is! From what did He created him?

(Chapter 30, ‘Abasa)

From a sperm drop He created him and enabled him. Then He eased the way for him.

Then He puts him to death, and buries him. Then, when He wills, He will resurrect him.

But no, he did not fulfill what He has commanded him. Let man consider his food.

We pour down water in abundance. Then crack the soil open.

And grow in it grains. And grapes and herbs. And olives and dates.

And luscious gardens. And fruits and vegetables.

Enjoyment for you, and for your livestock.

Praise the name of your Lord, the Most High, He who creates and regulates.

(Chapter 30 [al-A’la])

He who measures and guides. He who produces the pasture.

And then turns it into light debris.

Do they not look at the camels—how they are created? And at the sky—how it is raised?

(Chapter 30, [al-Ghashiyah])

And at the mountains—how they are installed? And at the earth—how it is spread out?

Monotheism was very clear in the early verses of the Quran. However there was no harsh attack or criticism of paganism. The main interest was revealing to the masses what kind of God Allah was: the Creator, the Merciful and the compassionate. It went further to remind the Quraysh that Allah is the Lord of the House, the Ka’bah.

For the security of Quraysh.

(Chapter 30, Quraysh)

Their security during winter and summer journeys. Let them Worship the Lord of this House.

Who has fed them against hunger, and has secured them against fear.

The second theme of the revelation that dominated early verses was a social one. It dealt with the decline and even the disappearance of the original tribal ethic that protected all members of the community. It carried a clear warning to the ruling elites who lacked any concern for the poor and marginalized. The Quran called for an end to false contracts and the practice of usury that had made slaves of the poor. It also emphasized the rights of the underprivileged and the oppressed; and commanded the rich and powerful to take care of them.

The command for social and economic justice was empowered with a warning: the Day of Judgment, when humans return to God for punishment or reward.

Woe to every slanderer backbiter. Who gathers wealth and counts it over.

(Chapter 30, al-Humatha)

Thinking that his wealth has made him immortal. By no means. He will be thrown into the Crusher.

When the sky is ruptured.

(Chapter 30, al-Inshiqaq)

And hearken to its Lord, as it must. And when the earth is leveled out.

And casts out what is in it, and becomes empty. And hearkens to its Lord, as it must.

O, Man! You are laboring towards your Lord, and you will meet him. As for him who is given his book in his right hand.

He will have an easy settlement. And return to his family delighted.

But as for him who is given his book behind his back. He will call for death.

And will enter the Blaze.

As for him who gives and is righteous. And confirms goodness.

(Chapter 30, al-Layl)

We will ease his way towards ease.

But as for him who is stingy and complacent. And denies goodness.

We will ease his way towards difficulty.

And his wealth will not avail him when he plummets.

Have you considered him who denies the religion? It is he who mistreats the orphan.

(Chapter 30, al-Maoun)

And does not encourage the feeding of the poor. So woe to those who pray.

Those who are heedless of their prayers. Those who put on the appearance.

And withhold the assistance.

Inviting the Hashim to Islam

For three years, Muhammad kept a low profile, preaching to only selected groups of people. Three years after the revelation had begun, Allah instructed him to deliver the message to the clan of Hashim.

And warn your close relatives.

(Chapter 19, ash-Shu’ara’)

And lower your wing to those of the believers who follow you.

And if they disobey you, say, then say, “I am innocent of what you do.”

Muhammad called forty-five men from the clans of Hashim and Muttalib for a feast of mutton and milk. As he started his address, trying to explain why he called for the gathering, his uncle Abu Lahab dispersed the crowd. So the Prophet invited them again and promptly addressed the family, not giving a chance to Abu Lahab to interrupt.

He said:

I celebrate Allah’s praise, I seek his help, I believe in Him, I put my trust in Him, bear witness that there is no God to be worshipped but Allah with no associate. A guide can never lie to his people. I swear by Allah that there is no God but Him that I have been sent as a Messenger to you in particular and to all people in general. I swear by Allah that you will die just as you sleep, and you will be resurrected just as you wake up. You will be called to account for your deeds. It is then either Hell forever or paradise forever.

His uncle Abu Talib replied:

We love to help you, accept your advice and believe in your words. These are your kinspeople whom you have gathered, and I am one of them, but I am the fastest to do what you like. Do what you have been ordered. I shall protect and defend you. But I cannot quit the religion of Abdul Muttalib.

Abu Lahab then said to Abu Talib: “I swear by Allah that this is a bad thing. You must stop him before the others do.” Abu Talib responded, “I swear by Allah to protect him as long as I am alive.”

Muhammad’s call to the Banu Hashim failed to convince new members of his clan to accept Islam. In the early stage of Islam, Khadijah, their daughters, Ali, and Zayd accepted the revelation unconditionally. Muhammad’s cousins, Ja’far ibn Abi Talib, and Abdullah and Ubaydallah ibn Jahsh and their sister Zaynab, were among the first followers. His uncles Abbas and Hamzah did not accept the message, but their wives did. Abu al-As, who had married Muhammad’s daughter Zaynab, refused the new religion.

Public Call

After the Prophet became sure of Abu Talib’s commitment to his support and protection, he expanded his preaching mission to include the entire Meccan community. Soon after his meeting with the Hashim and al-Muttalib clans, he stood on al-Safa, the small hill in the center of Mecca, close to the Ka’bah, and called out as loudly as he could to every clan, mentioning them by name and asking them to come over to him. In no time, the word spread all over Mecca that Muhammad had something important to announce. People were rushing to him from all quarters of the city. When they gathered around the hill, he said: “If I were to tell you that there were armed horsemen in the valley heading towards Mecca to attack you, would you believe me?”

“You are trustworthy, and we have never known you to tell lies,” they answered. “Well, then, I am sent to you to warn you against grievous suffering.”

The Prophet continued his warning, addressing each clan by name, and said,

God has ordered me to warn you. It is not in my power to secure any benefit for you in this life, or any blessing in the life to come, unless you believe in the oneness of God. People of Quraysh, save yourselves from hell, because I cannot be of any help to you. My position is like one who, seeing the enemy, ran to warn his people before they were taken by surprise, shouting as he ran, “Beware! Beware!”

Not a single voice was raised in approval or support as they began to disperse. On the contrary, he received insults from some of the men present, especially from his uncle Abu Lahab.

Muhammad’s public address was a significant event in the history of Islam. It was the beginning of the social reforms of the Arab society. The call for monotheism did not mean just the substitution of a single god for the collection of all the idols housed in the Ka’bah; it also meant complete change in the social, cultural, and political life of Meccan society.

Muhammad was persistent in his efforts to deliver his message to the Quraysh. He spoke to the Meccans whenever he passed by a gathering of the idolaters. He also started criticizing their beliefs and the worthlessness of their idols. Then he began worshipping Allah before their eyes in the Ka’bah and reciting the verses of the Quran in a loud voice. Few of the Meccans responded to his call or accepted Islam.